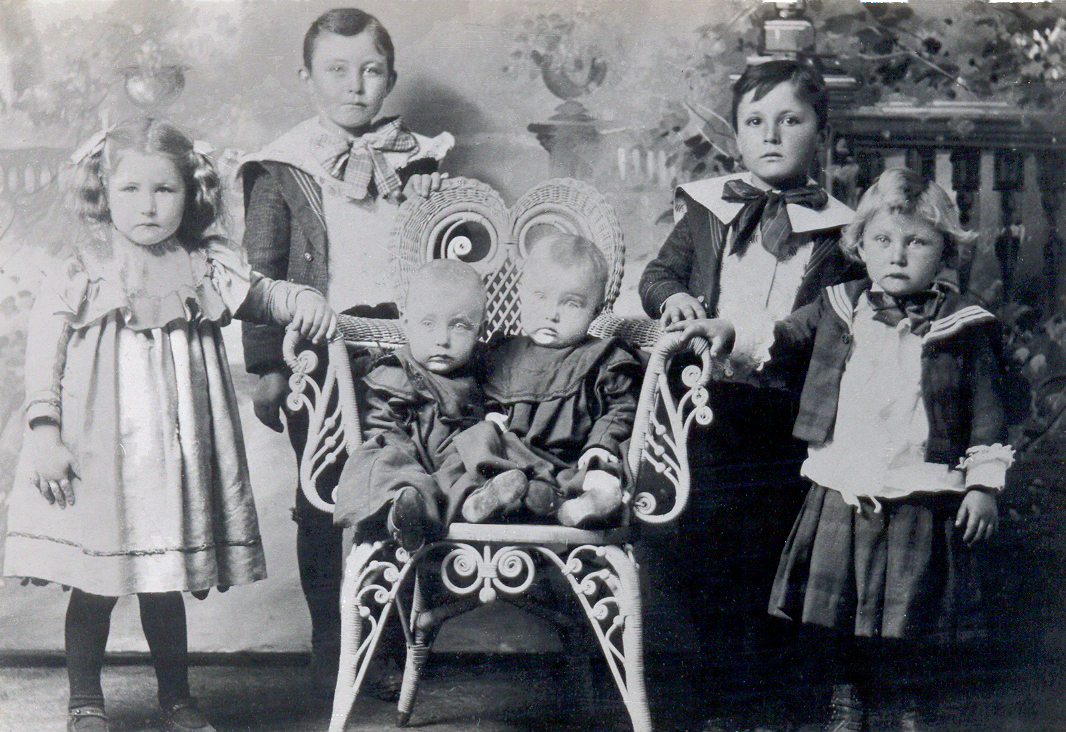

February is a cold month in Kansas, especially with the prairie wind, and on February 2, 1899, it was 22 degrees below zero. Henry and Carrie Janzen were expecting the birth of their fifth child, and on this day she went into labor. Attempts to get a doctor had failed and Henry had moved the bed into a room where there was a heating stove. According to the story Carrie later gave a newspaper, she had milked the cows and scrubbed the floor when it became apparent that the time had come. She said that when the baby finally came she got up and cleaned up, but felt bad, and so laid down to rest. Shortly afterwards, a second baby arrived, so she got up, cleaned it, but still felt bad. When the third baby came, she was too tired to clean it and finally asked my grandfather for help. It was not until the next day that the doctor finally arrived, and he expressed concern because the afterbirth looked abnormal. With that, my grandfather led him to another bed and showed him the triplets; Edward Carl, Edmund Ernest, and Edna Clara. According to one account, the doctor had a wooden leg, and when he saw the triplets he was so excited that he started dancing. It is also said that his charge for the visit was $10, but he returned $7 so a photograph could be taken. Perhaps this is the photograph that is shown on the next page. I have often wondered if these were the first European triplets born in Kansas.

The names given to the triplets were carefully planned so the initials of Edward Carl and Edna Clara would be the same as with their grandfather’s (Edward Carl), and Edmund Ernest would be the same as his uncle, Edward Ernest.

I can’t imagine having your family unexpectedly go from four to seven children in one day, especially when the other four children weren’t that old: Henry 6, Albert 5, Rosa 4, and Leroy 2. The house was not that big and finances were limited, but these early homesteading families knew how to survive. Eventually my grandfather’s children would become a sizable workforce and make him wealthy. I once heard the finances of these pioneer families described this way: the first six years it costs to raise a child, the next six years their work equals their expenses, and the next six years they pay for the first six. As you will see, my grandfather derived a large profit from his children.

The Janzen Triplets (left to right, Edmund Ernest, Edward Carl, Edna Clara)

I don’t know a lot about my father’s early childhood, and most of what I know I got from my mother. I know that as a child he never had a toy and his parents never read children’s books to him. My mother said that when they married he had not heard of Cinderella, or any of the fairy tales. To rectify this, she got all of these books from the library and had him read them.

The event that probably changed my father’s life the most was the death of his triplet brother, Edmund, in August of 1899. The cause was considered weed poisoning in cow’s milk. As a result of Edmund’s death, my father was paired with his sister Edna, and therefore did not enjoy the male camaraderie of his brothers to the degree that he would have had Edmund lived. As a triplet, he was also smaller than his brothers, and this seems to have made a difference. My mother said he was also teased. In spite of these things, my father thought he had a normal childhood and never resented his parents or siblings. If fact, as an adult his favorite vacation was to go to Kansas and visit family, where he was always received with open arms.

The absence of toys and ignorance concerning children’s stories is not an indicator of neglect by his parents, but shows the survival mode that underpinned life on the Kansas prairie at that time. However, as the photographs of the Janzen family show, the children were always well-dressed, at least in those photographs. My grandfather was proud of his family, and their appearance was important to him.

I am sure that the family was always well-fed, though the menu might seem Spartan by 21st century standards. My father spoke of having potatoes with clabber milk for the evening meal and, being wheat farmers, there was always an abundant supply of bread. One of my father’s favorite stories was about a dried breakfast cereal they had, called VIGOR. It was similar to corn flakes, which my father always referred to as “fence post shavings.” At one time the makers of VIGOR had a promotional, and in each box of cereal was a letter, V, I, G, O, or R. There was a prize if you could collect all five letters. One of the letters was difficult to get, and my father said that one morning while he was dressing he heard his father give out a yell, they finally had all five letters. As winners, the company sent them a barrel of semi-porcelain English china made by Clementson Brothers. After his parents died and things were being divided, my father got a bone dish from this set and one of the twelve chairs that were around the kitchen table.

The Janzen Children in 1900. Standing (left to right), Rosa, Henry, Albert, and Leroy, seated is Edna (left) and Edward (right)

As the family grew to ten children, my grandmother baked twelve loaves of bread every other day. It is interesting how certain foods my father had growing up remained his favorite after he left home. To him, fried bologna was far superior to a filet mignon, and nothing went with it better than creamed corn. His choice of candy also seemed strange to me. One of his favorites was horehound drops, a hard candy made from extract of the horehound plant, and it had a bittersweet taste that I found generally disgusting. I guess that this was the kind of candy his father bought the children at the general store, and they loved it.

Bone dish from the VIGOR set of China

I remember my father saying that every fall his father would be gone for several days and return with a wagon load of apples and a barrel of cider. I guess the apples were dried, or turned into applesauce, and this lasted them through the winter.

My father was always very neat and kept things well organized. This was probably a combination of his German upbringing and having five brothers and four sisters. He told me that he and two of his brothers shared a room. There was one dresser, and each of them had two drawers in the dresser and a third of the top to keep their hair brushes and other items. I doubt if he ever considered using more than his third. I remember my father saying they never had underwear and his dress clothes consisted of one wool suit. He said he knew what hell was like having to sit through a church service in the summer in a wool suit with no underwear.

By 1907, the Janzen family had grown to six boys and four girls. A seventh boy, Walter, died in infancy. With this brood, my grandfather had the labor to make the transition from farming to agriculture. Well-established in the family system at this time was the division of labor by sex. My grandmother and four girls were in charge of the house, which meant cooking, laundry, and cleaning, while my grandfather and the boys did the farm work. Actually, this division of labor was not fair, because the last two Janzen children were girls, Nellie and Thelma. This meant that Rosa and Edna were in their teens before Nellie and Thelma started school, and along with their mother, were doing the bulk of the female labor. I always remember my Aunt Rosa as being a happy person, but my Aunt Edna played the role of what my mother called “Pitiful Pearl.” She referred to herself as “Cinderella” and claimed that she always did more than her share of the work. Who knows?

This photograph indicates the magnitude of Henry Janzen’s farming operation. pictured are 24 to 25 people and 26 horses.

My grandfather’s farming activities were diversified and, beside growing wheat, he also had cattle, and perhaps other things that I am not aware of. I know my father talked about driving cattle to Ellsworth, Kansas. Naturally my grandfather had a large number of horses, because they pulled all the farm implements. My father said that over the winter the horses were not used that much, and in the spring, they would have to be “broken” again (broken means tamed). It is hard for me to imagine my father on cattle drives and breaking horses in the corral. He also mentioned the time his father told him to plow a field that had never been cultivated before, where watermelons were planted as a cover crop. He said that it produced an amazing number of melons. This reminds me of a story that my mother tells about her first visit to Kansas. She said that all the Janzens loved watermelon, and that sister Rosie’s eyes danced when she saw one. They would buy watermelons by the truckload and just eat the heart.

When my father was growing up it was an accepted practice for children to earn money for their father, and my grandfather had this down to a fine art. When the boys were young, after the wheat was harvested, he hired them out to other farmers. Pay for this labor naturally went to my grandfather. My father said that each year before school started his father took them all to the store for new clothes. The money he had earned went to buy his clothes, and one year there was a small amount left over. He was hoping that his father would give him this money, but instead it went toward the purchase of his younger brother Herbert’s clothes. This indicated how my grandfather thought about money. My father was working for the benefit of the family, not himself. In a way, there was a communal economy among these homesteading families, and it probably insured their survival.

As the boys got into their teens, my grandfather would buy a farm and have two of the boys and one of the girls run it. My father always refers to periods when he would work on a new farm as his “Batching Days,” batching being short for bachelor. In his case, he and his older brother Roy (the Leroy was dropped) worked a farm, and sister Edna did the cooking and laundry. Using this scheme, my grandfather was able to acquire a lot of land, and I suspect that eventually he was considered wealthy by the standards at that time. Even with a large family, my grandfather had to hire outside labor, and my father would often tell stories about the Bohemians that worked with them. One thing that he learned from the Bohemians was how to cuss. This was, of course, in their language (whatever that was) so he would say “Yaki dum fas coogie” (spelled phonetically) to relieve his frustration, and not break any church rules about swearing.

With so many horses and cattle, hay was important, and my father said this need was filled by creating large piles of hay called “hay stacks”. These enormous piles of hay had to be constructed in a special way so they would drain water. My father often told about the time his father put him in charge of the hay. His job was to stand on the stack, and as the wagons brought the hay he had to spread it in a certain way. It was my understanding that there was a certain amount of prestige in being in charge of this job.

My grandparents spoke German in the home, and my father still remembered poems that he had memorized in German. It was common across the country for people of German descent to speak German and in major cities with large German populations, like Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Milwaukee, there were even newspapers printed in German. This practice came to a relatively sudden halt with the start of World War I. People of German decent faced a conflict between pride in their ancestral heritage and national loyalty. As a means of demonstrating their national loyalty many families ceased speaking German.

Wilbert Janzen plowing behind his father’s nine-horse team

Religion was a big part of the Janzen’s lives, and before every meal my grandfather would give a lengthy prayer. I remember these when I visited Kansas, and when my grandparents would visit us. It is interesting that there is a sharp division in German culture regarding smoking and drinking alcoholic beverages. Most of the early breweries in the United States were started by Germans, and I suspect these were the Catholic Germans and not the Baptist Germans. Smoking and drinking (in a limited way) did emerge among my father’s brothers, and it was their children who influenced them. My cousin Leon told me that when the cousins returned from World War II many of them smoked and drank beer and introduced these to their father. I suspect that smoking and drinking was done behind the barn and outside the view of their wives.

My grandfather retired from farming around the age of fifty-five. His retirement was not his choice, but my grandmother’s, and she forced it upon him in an interesting way. While he was in Kansas City selling cattle, she purchased a house in Lorraine and had the boys (her sons) move everything there. When my grandfather came home the house was empty. Yes, my grandmother did have the money to buy a house. When her parents died, she had inherited land, and when the oil boom hit Kansas oil was discovered on her land. I believe I am correct that the oil company gets seven-eighths of the oil a well produces and the landowner one-eighth. My grandmother took her one-eighth and had the oil company pay her half, with the other half divided into tenths and a share given to each of her children. Each month, my parents received an oil check, maybe for twenty or thirty dollars. Finally, when the well went dry it produced gas and the check for that was eventually a dollar or less. Although my grandfather’s retirement was forced upon him, I am sure that every day he went to his sons’ farms and told them how to run things. I say this because this is the way the sons acted when their children (my cousins) started farming. My cousin Leon’s father, Wilbert, was still telling him how to farm when Leon was in his 60s.

The Janzen family, 1918. Seated Henry and Carrie, standing, left to right, Herbert, Henry, Nellie in front of Henry, Rosie, Wilbert, Albert, Edna, Thelma in front of Edna, Roy, and Edward

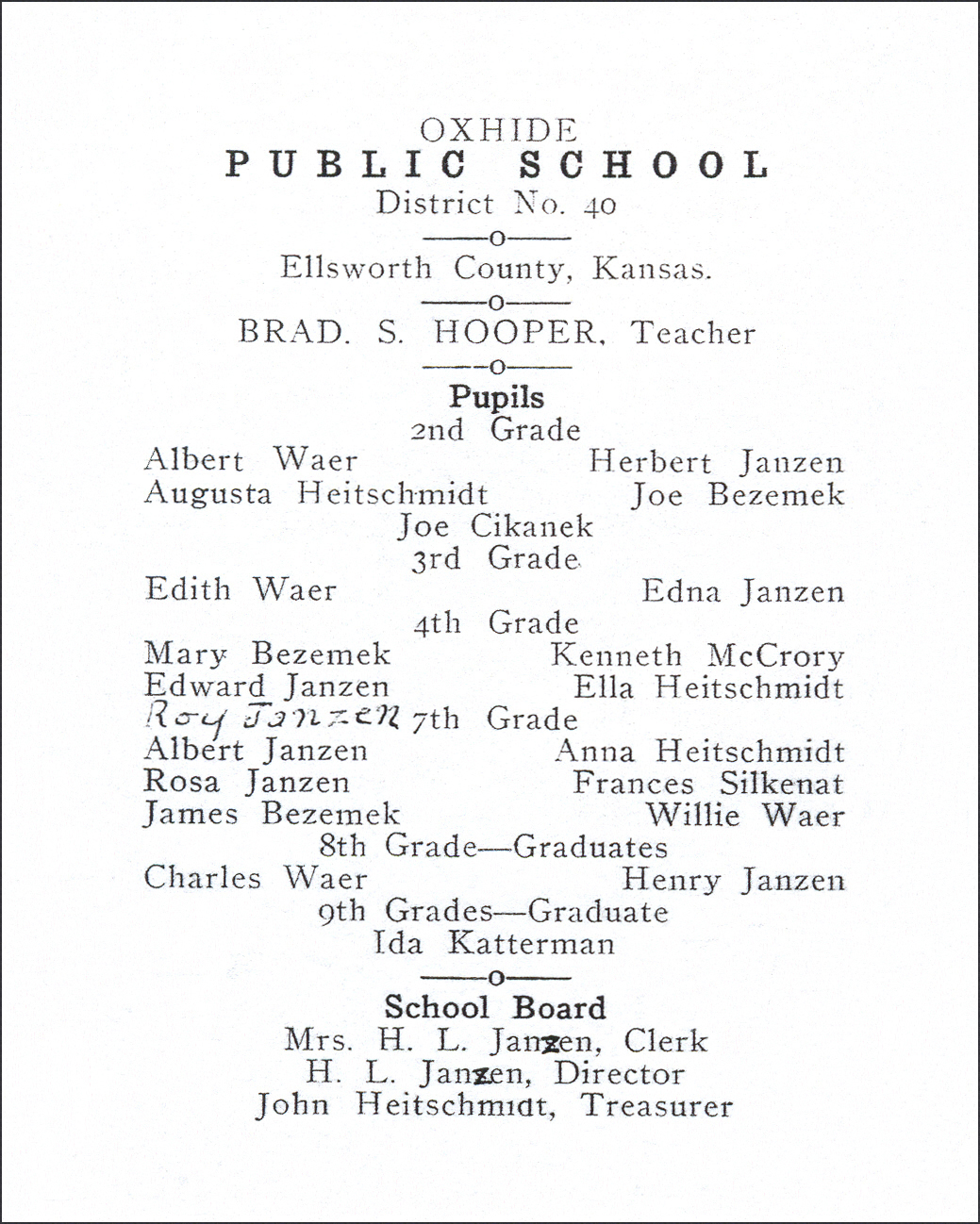

My father’s early schooling consisted of going to a one-room school through the eighth grade. It was located east of Lorraine in an area referred to as the “Oxhide.” A roster listing the students in the school is titled, “Oxhide Public School.” Of the 21 students, six were Janzens. Without a date, this list is difficult to interpret, but when my father was in the fourth grade, his sister Rosa (who was four years older) and brother Albert (who was five years older) were just in the 7th grade, while his brother Henry (who was six years older) was in the 8th grade. Perhaps not all children started school at the same age, and some may have had to repeat a grade because of illness. It was always my impression that my father’s parents took a neutral view towards education, since going to high school appears to have been optional. However, their participation in running the school system, as seen on the above roster, seems to indicate that this was not the case.

I have sixteen hand-written pages of notes that my father’s sister Edna wrote about her childhood. Here is an excerpt, containing what she says about the “Oxide” School.

Remember the “Old Oxide School, my the distance we had to walk, three and a half to four miles, how cold we’d get, we always liked to stop at the Bezemeck home to warm up, this was the half way place, then we go on, and many a time we would stop there in the evening and Mrs. B. would have lots of homemade bread baked that day, she would slice a loaf or two and we ate syrup on it, and also had hot coffee, then we went on our way rejoicing.

How we would get lost in Gregory’s large pastures on a foggy morning. The Texas longhorn cattle Gregory has in the pasture we walked through, there were hundreds, remember how they would circle around us then take out after us, this one evening home here they came, seemed Leroy was always walking with Anna Heitschmidt and she told Leroy let’s kneel down and pray, Leroy said you can pray but I’m heading for the fence, my how we all ran, we barely were over the fence and the cattle were just at our heels.

Roster from the Oxhide Public School for 1909

Today an 8th grade education is considered only a step in the educational process, but in the early 20th century it was considered a noteworthy achievement. I have a copy of an 8th grade final exam dated 1895, from a school in Salina, Kansas. I doubt if today the average high school senior could pass this exam. The importance of an 8th grade education is reflected in the elaborate diploma my father received for this accomplishment.

The Janzens’ “School Bus,” circa 1909

My father continued his education by going to the Lorraine High School, and then he could drive a rig to school. The photograph titled, “Ed and Herbert’s school rig” with a date of 17-18 (1917-1918) shows what I always referred to as my father’s school bus. As an aside, I have the impression that at times the Janzen brothers might have been “hell on wheels”. My father had numerous stories of how they turned the rig over, the horses got loose, and they had to walk home. From what I remember of my uncles Al and Roy, this is believable. Teenagers were probably just as wild with horse-drawn rigs as they are today when they get cars. Actually, I know very little about my father’s high school years. He was on the basketball team, and he told me that he was president of his class. I later learned that he and Anna Schroeder were the only ones in his grade.

The Oxhide School, circa 1909. Edward is in the second row, second from the left (Note the barren landscape, add some craters and it looks like Mars)

I still have some of my father’s high school text books, and they give an interesting insight into his education. I don’t know why, probably out of nostalgia, but I‘ve never been able to discard these books. They were obviously very important to him because he hauled them from Kansas, probably to Mississippi, and to all the places that he lived in Louisville. He wrote his name in most of these books, and sometimes the year.There are eight school text books in the collection, and one other titled Freckles, that I would call popular contemporary fiction of the time. It was published in 1904, and on the inside is written:

A Merry Christmas

& A Happy New Year

For Edward

From Frieda Hornfeld

1917 Lorraine High School Basketball team. Edward Janzen is standing at the far right

All of the text books are recent editions (the earliest being 1905) and the depth to which the subject matter is treated is impressive. Four of the texts are literary works: Lady of the Lake by Sir Walter Scott, The Snow Image and Twice Told Tales (together as one book) by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ben Hur by Lew Wallace, and The New Hudson Shakespeare. In the latter book is written:

Edward C. Janzen Senior 1917-18 Lorraine High School

His report card for his junior year indicates that he took a course in botany and it included a laboratory. I suspect that his book, Practical Botany (545 pages), was the textbook, and I would judge it equivalent to a college text on the subject today. My father’s report card for his senior year indicated that he took English III and English History. His text book for the latter class was The History of England (646 pages) and A Short History of England’s and America’s Literature, was used in English III. Both of these are impressive texts and would be college level books by today’s standards. It should be remembered that not only do these books treat the subjects in a sophisticated way, but the teachers had to be well-versed in the subjects in order to teach from them. My father’s diploma from the Lorraine Public School is dated April 26, 1918, and it is larger than any of my university diplomas. There was an elaborate formal invitation to the commencement which mentioned the class colors, flower, and motto. Only 37 years had passed since homesteading began in Kansas, but already Lorraine was copying what was happening in the cities.

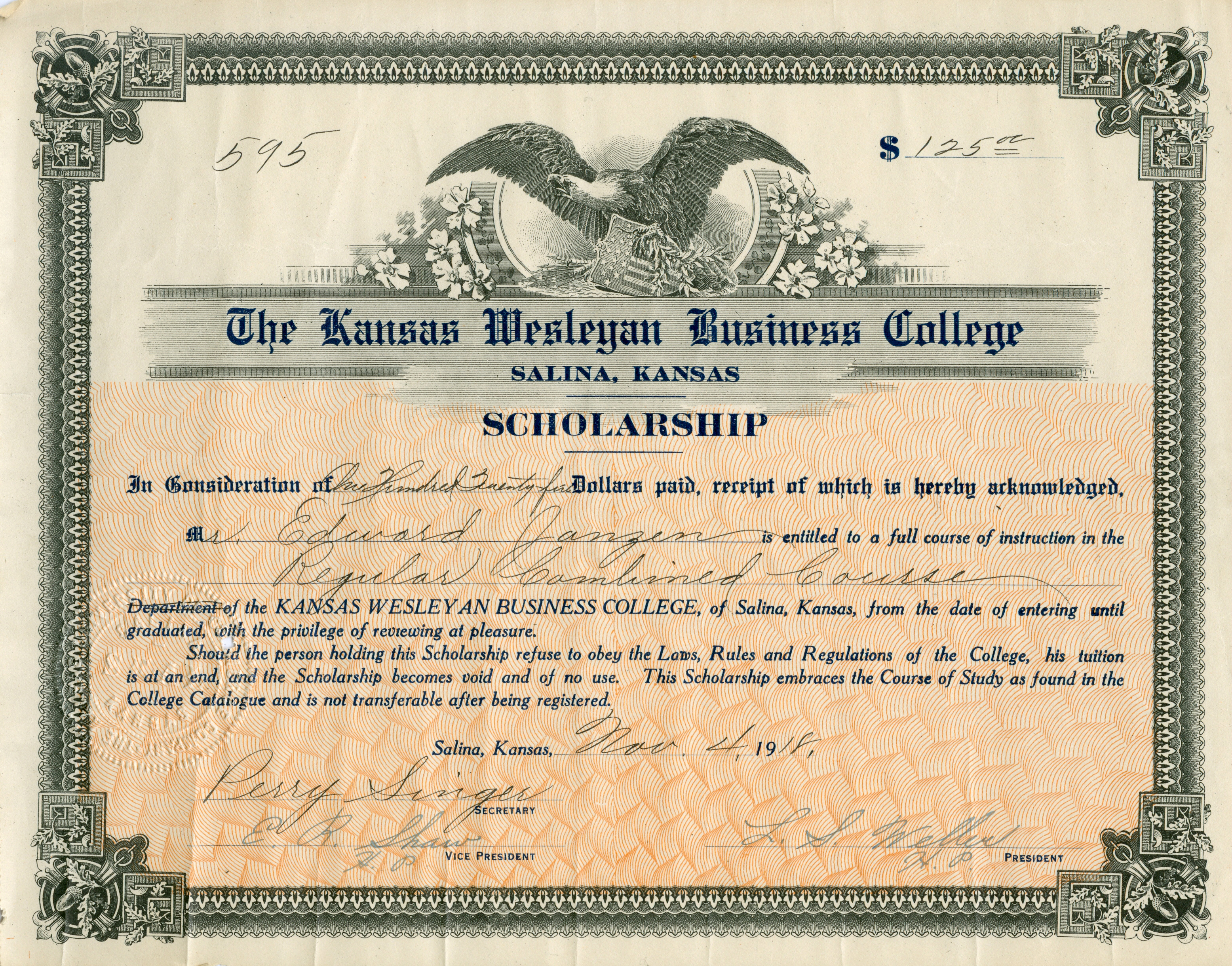

It was my father’s older sister, Rosie (the nickname she acquired for Rosa) who encouraged him to continue his education beyond high school. I never thought about why she did this, but perhaps her motivation was my father’s grades during his Senior year. They were impressive. For the five subjects he took, his year’s average grades were A+ in four classes and an A- in the other. In the fall of 1918, he entered Ottawa University in Ottawa, Kansas, to take classes in business. Unlike his brothers who stayed in farming, this pointed him in the direction of the corporate world.

At this point, the sequence of events becomes unclear, and I attribute this is to two major events that occurred simultaneously: the Spanish Influenza and the end of World War I. According to my cousin Ronald Nelson, the family historian, on September 12, 1918, my father received his induction notice for military service. He never talked about this, and I don’t know if this occurred just before or just after he went to Ottawa. It appears that induction did not mean a call for duty, and my father was still able to go to Ottawa University. Since the Armistice ending the war was on November 11, 1918, I don’t know if these late inductees were told not to report, or if they assumed this meant they no longer had an obligation to report. In either case, my father’s ties to the military ended.

It was also around 1918 that the Spanish Influenza hit Kansas. This disease, which is estimated to have killed 50 million people world-wide, was the most devastating epidemic in human history. When the flu struck, at the urging of his parents, my father left Ottawa, and returned home. By the end of 1918 the threat of the flu lessened, but instead of returning to Ottawa he enrolled in The Kansas Wesleyan Business College in Salina, Kansas. I found a certificate awarding my father a $125 scholarship to the Salina school, and this may be the reason he didn’t return to Ottawa. In a note my father wrote about this time period he says that in the fall of 1919 he left for Charleston, Mississippi, to be employed at the Lamb-Fish Lumber Company as an assistant bookkeeper. Therefore, he never completed his degree, though it is my understanding that the College was responsible for getting him the job in Mississippi. So, at the age of twenty my father left Lorraine for a career outside

farming. I doubt if he had ever been outside Kansas, and moving to Mississippi, away from his family, had to have been a traumatic experience. Although he never returned to Kansas, I believe that for the rest of his life he considered himself a son of the Sunflower State.

Edward’s Scholarship to Kansas Wesleyan Business College. Since this certificate refers to $125 paid in full, it is not known if the regular fee is higher and the scholarship reduced the fee to this amount