In early December 2020, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) announced a wolf hunt to take place in November of 2021, marking its first wolf hunting season in seven years. 1 Under Wisconsin state law, the state is annually required to allow a wolf “harvest,” the official name of the hunts, from the first Saturday of November to the end of February. 2 Mere weeks before this hunt, the American gray wolf (Canis lupis) was stripped of the protections it had enjoyed for 40 years under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The removal of federal protections of the gray wolf enacted this law, which required the state to hold a hunt. However, the decision to remove gray wolves happened in the middle of its hunting season and some saw not holding a hunt while the state could hold one as a violation of its requirement. In response, Hunter Nation Inc., a Kansas based hunter-advocacy group, sued the Wisconsin DNR to expedite the season from beginning in November of 2021, to starting in February of 2021, only lasting until the end of that month. 3 The Courts found that the Wisconsin DNR failed its requirement as a state agency by refusing to establish an open hunting season until the end of February. Thus, the season began February 22nd at midnight and lasted until the end of the month. Wolf advocates and conservation groups opposed this hasty harvest, mainly due to the breeding season for the gray wolf, happening only once a year from late January to early March, beginning during this hunt. “[K]illing pregnant wolves generally eliminates any spring pup production in their respective packs,” and the risk of doing so was unreasonably high during this hunt. 4 But they could do nothing as a quota of 200 wolves was set (119 for the state and 81 for the Ojibwa). 5 From February 16th to the 20th, 18,503 people applied for a harvest license. 6 And based on the 119 non-native hunter quota, 2,380 were approved, and 1,584 licenses (65 percent of those awarded) were sold. 7

On February 24, 72 hours after the season started, the hunting season ended early due to the quota already being surpassed. Two-hundred-eighteen wolves were “harvested” over three days, exceeding the set quota. 8 The number of wolves hunted over these three days, while similar to previous years, was normally reached over the course of four months. Moreover, these were all non-native hunter kills, since the Ojibwa chose not to participate in the late winter “harvest,” saying it was “especially wasteful and disrespectful.” 9 That means that non-native hunters killed 99 more wolves than authorized. Sources also say that the quota was surpassed before the hunt even ended, as non-native hunters checked-in 182 wolves on February 19, 2021. 10 Before the hunt, Wisconsin reportedly had around 1,195 wolves. However, Wisconsin’s wolf management goal is 350 wolves on non-reservation land, one-third of the estimated number. Even though the season was contentious, the Wisconsin DNR still saw it as successful, as it decreased the number of wolves, bringing it closer to the department’s preferred level. 11

Gray Wolf (Canis Lupus). Image by Wikiimages from Pixabay

The American gray wolf was listed under the ESA for nearly 45 years before its removal. Only 54 species have ever been removed from the list successfully and 56 species downgraded from “endangered” to “threatened” status since the Act’s inception. 12 The process is difficult, reflected in the small number of successful removals. However, this was not the first time the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has attempted to strip the protections on gray wolves. After four failures and one small win, most of the gray wolf population remains protected under the ESA. On every attempt, the Service claims that some part of the wolf population has recovered enough to be delisted. On this most recent attempt, the USFWS decided to delist all wolves across the United States, sparking major controversy due to the scale of its attempt. In response, national conservation groups sued the agency for, primarily, not adequately analyzing the remaining threat against wolves that still warrants their federal protections. As you will see, this attempt appeared hasty, seemingly skipping over many steps in the delisting (removing from a list, specifically when stripping security or protections) process. By inspecting the events closely, they illuminate ulterior motives that are potentially political, separate from the official listing process, which could be detrimental to the future of the American gray wolf and its status under the ESA.

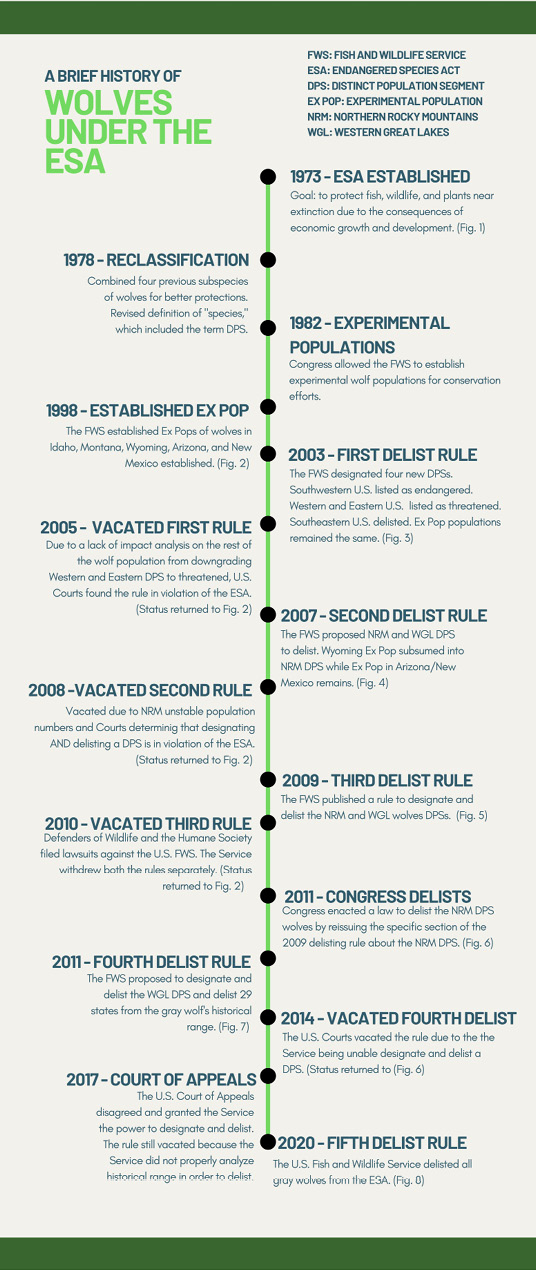

“A Brief History of Wolves Under the Endangered Species Act” Infographic

Created by Lucien Akira DeJule

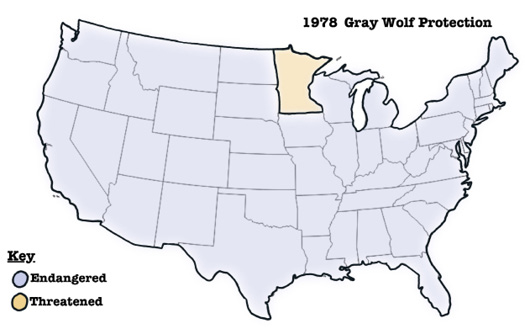

1978 Gray Wolf Protections Map (Figure 1)

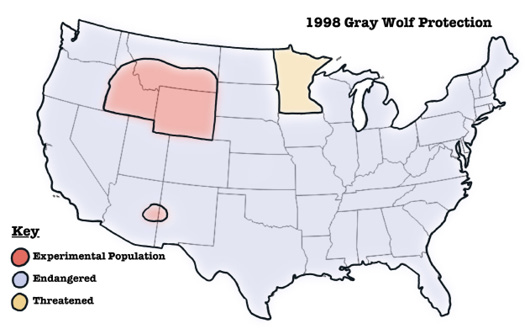

1998 Gray Wolf Protections Map (Figure 2)

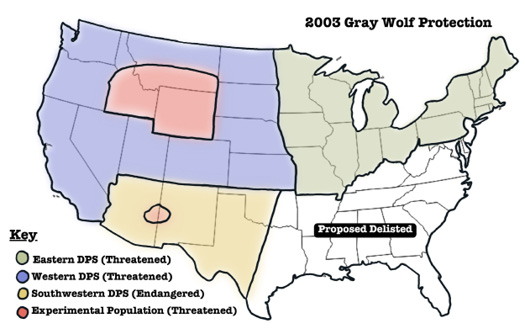

2003 Gray Wolf Protections Map (Figure 3)

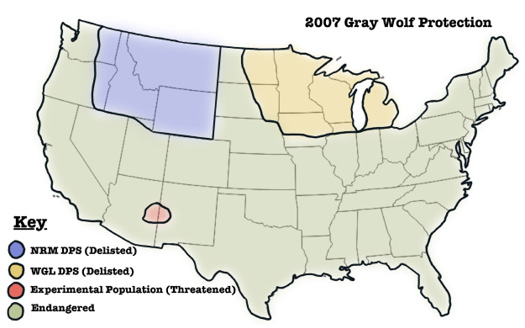

2007 Gray Wolf Protections Map (Figure 4)

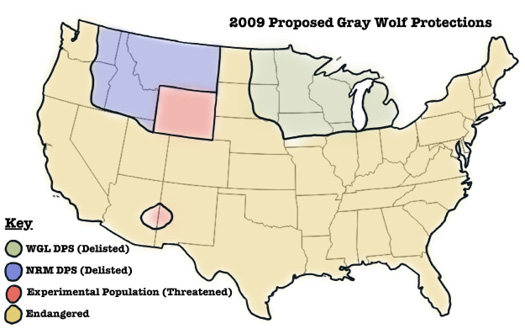

2009 Proposed Gray Wolf Protections Map (Figure 5)

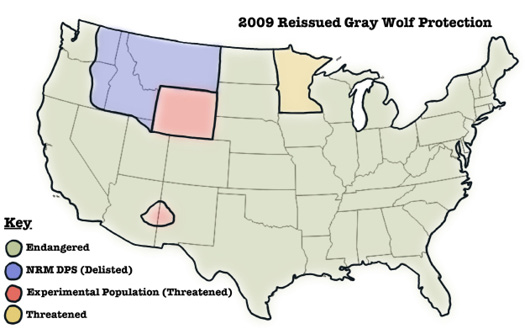

2009 Reissued Gray Wolf Protections Map (Figure 6)

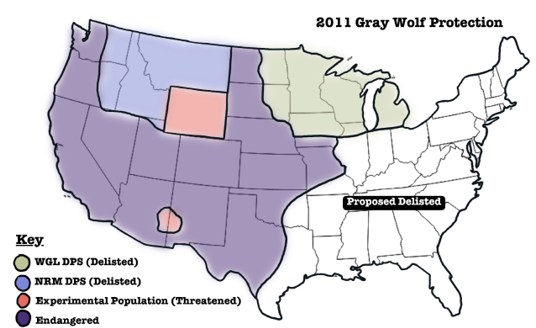

2011 Gray Wolf Protection Map (Figure 7)

2020 Gray Wolf Protection Map (Figure 8)

The Endangered Species Act

In 1973, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) became law, providing legal protections for many plant and animal species, including the American Gray Wolf. There has never been an accurate count of gray wolves in the United States. At the beginning of European settlement of the future United States, estimates varied between 250,000 and two million wolves. 13 By 1960, hunting, poisoning, shooting, and government-funded wolf-extermination efforts had caused gray wolf numbers to plummet as they were extirpated from nearly 90 percent of their original range. 14 And by 1974, aside from a few scattered individuals and a larger population in Alaska, wolf numbers had dwindled to a shocking 1,000 total, far less than even one percent of their estimated original population, residing in northern parts of Minnesota and Isle Royal, Michigan. 15 Following the listing of the gray wolf under the ESA, efforts were made to support an increase in their numbers through protections, sanctions for wolf hunting, and reintroduction programs. Over the next 40 years, their population rebounded to nearly 6,000 in the lower 48 United States and continues to grow. 16 To help explain the history of the status of gray wolves under the ESA, this article includes a timeline of that information. It also includes maps that visualize the changing protections of wolves over the course of the listing.

This resurgence has not pleased everyone. During the decades since their listing, the USFWS has made five attempts to delist the gray wolf. According to the ESA, there are five requirements for a species to be listed: “(A) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range; (B) Overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; (C) Disease or predation; (D) The inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or (E) Other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.” 17 Of these five factors, a species can be listed based on one, more than one, or the cumulative effect of one or more of these factors. 18 But, if a species does not or no longer meets these requirements, the Service “must remove the species from the Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants”. 19 Even though the USFWS claims its decisions are neutral and based on scientific evidence, continual USFWS attempts at delisting gray wolves raise suspicions about political influence. In 2015, a year before Donald Trump was elected president, a survey done by the Union of Concerned Scientists found that 74 percent of the scientists working at the USFWS thought that “political interests” were considered too heavily in making policy and regulation decisions. 20 Even though Congress managed to delist a population segment of gray wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountains in 2011, almost every other attempt at delisting failed due to lawsuits filed by various conservation groups like the Defenders of Wildlife and the Humane Society of the United States. However, in 2020, the USFWS published a proposed rule that would return the wolf to peril.

Delisting the Gray Wolf

On November 3, 2020, USFWS wrote a proposal to delist the American gray wolf entirely from the ESA. On January 4, 2021, the USFWS acted on this proposal, removing all gray wolves listed as a threatened or endangered species in the lower 48 United States. Before this “Final Rule” came into law, gray wolves were listed as two entities: “C. lupus in Minnesota, listed as threatened; and C. lupus in all or portions of 44 U.S. States and Mexico, listed as endangered.” 21 Originally, these two groups were listed as distinct and separate species due to the constraints on the statutory definition of “species” under the ESA in 1973. At the time they were listed, though, in order to better manage the dangerously low population in the lower 47 United States (sans Minnesota and before the Northern Rocky Mountain DPS was delisted), the USFWS had listed the two species together. 22

Image by OpenClipart-Vectors from Pixabay

However, due to this hasty listing, the Service attempted to argue that gray wolves could be delisted solely because they did not meet the statutory definition of “species.” Prior to 1978, the Endangered Species Act defined “species” as an overarching term that includes all subspecies of fish, wildlife, or plant and “any other group of fish and wildlife of the same species or smaller taxa in common spatial arrangement that interbreed when mature.” 23 For clarity, “taxa” is a term that is used in the science of biological classification which, in this case, denotes variations of a species sharing a common ancestor. Then, in 1978, Congress amended the latter half of this definition, changing it from “any other group” to, “any distinct population segment of any species of vertebrate fish or wildlife which interbreeds when mature.” 24 This revision restricted the application of this definition specifically to vertebrate populations, but because of this change, listing a certain group of a “species” is now not restricted to just formal taxonomic terms, but includes subspecies, and for vertebrates, distinct population segments.

A distinct population segment (DPS) is a statutory, jargonized phrase used only by the ESA to constitute a “species.” In essence, “this term allows population segments that are sufficiently discrete and significant to be considered their own ‘species’ within the context of the ESA, despite belonging to a larger taxonomical species.” 25 In the case of the gray wolf, the only distinction between the two groups was their location (Minnesota versus the rest of the lower 48 United States). Because of that, if wolves were listed after Congress revised the definition of “species,” these two ‘species’ would be considered DPSs. In its argument, the USFWS conducted genetic research that illuminated the genetic similarity among the two groups of wolves due to their interbreeding. 26 Specifically, the Service highlighted wolves in Michigan and Wisconsin as being genetically similar to those in Minnesota because of their proximity. Through that point, the USFWS concluded that under the current ESA, the two entities were unlikely to be listed as species. Thus, through an error that was never revised, the USFWS wanted to delist these two entities based on it. This was made possible by a 2019 revision of the ESA’s implementation policy. This revision states the Service must “distinguish between a ’listed entity’ and a ‘species,’” and concluding that “an entity that is not a ‘species’ as defined under the Act” should be removed from the List." 27 However, this was not the only argument for delisting. And instead of just basing its argument on a technicality, the Service also provided more science-based evidence for the decision.

To accomplish this, the Service engaged in a bit of creative accounting. Since legally, gray wolves were listed as two entities (Minnesota and the lower 48 United States), the USFWS decided to use three different methods of assessment to determine the status of the American gray wolf. It assessed the gray wolf population in three ways: as separate groups (Minnesota and the other lower 48 United States), as combined into a single entity (without the Northern Rocky Mountain (NRM) wolves, which had already been delisted), and as a single gray wolf entity that includes all the gray wolves in the lower 48 states (including the NRM wolves). 28 Based on its genetic analysis of all the wolf populations covered under the ESA, the USFWS concluded that the DPS designation wasn’t meaningful and that all gray wolves in the lower 48 United States should be combined into one entity. This method differed starkly from the USFWS’s previous attempts to delist the gray wolf. In previous attempts, the agency designated a certain DPS of the population in order to delist that group. Because this effort failed many times, the Service decided instead to lump all gray wolves into one big population whose numbers, it could then claim, were large enough to indicate that the wolf could safely be delisted.

Image by Mostafa Eltturkey from Pixabay

The Service connected many dots in order to coalesce the population. The Service already genetically connected wolves from Minnesota to wolves from Michigan and Wisconsin—more commonly known as the Western Great Lakes (WGL) DPS. However, it provided similar evidence to support connections made between the West Coast States wolves and the North Rocky Mountains (NRM) wolves. Since the NRM DPS was previously removed from the List in 2011, through genetic analysis, the USFWS linked wolves in western Washington, western Oregon, and northern California with the NRM DPS to argue for their delisting. 29 If the West Coast wolves and the NRM wolves were not distinct from each other, then their proximity would warrant their combination. Because of these genetic interrelations, the USFWS proposed that all these wolves be seen as one entity: the wolves of the lower 48 United States and Mexico which includes wolves from the NRM DPS even though they are already delisted.

The “Final Rule” from the Service concludes that the existence and recovery of the two largest meta-populations (spatially separate populations of species that interact, on some level, with the rest of the population) of wolves—the Western Great Lakes and the Northern Rocky Mountains—is proof that gray wolf populations can now sustain themselves. 30 However, this analysis does not take into account all protected gray wolves across the entirety of their listed range—Minnesota and the other lower 48 United States and Mexico. Specifically, the Service’s determination highlights the WGL DPS and the NRM DPS as the basis for claiming their recovery. Although the WGL DPS contains over 4,000 wolves (two-thirds of the protected population), it does not account for every wolf protected under the ESA. 31 The lack of research and analysis done on the rest of those states sparks suspicion, as it raises the question: how does someone determine if a species is “recovered?” The sheer scale of this delisting caused mixed reactions in the wider American community. On one hand, hunting, farming, and more rural communities, like the ones in Wisconsin, rejoiced at the opportunity to cull wolf populations to manageable levels for the safety of their livestock and families. However, this ruling did not last for long as conservation groups felt this “Final Rule” was unlawful and brought legal action to protect the wolves once again.

Re-listing the Gray Wolf

In the aftermath of the Wisconsin wolf “harvests,” in 2021, the Defenders of Wildlife, Wildearth Guardians, and the Natural Resources Defense Council, conservation groups dedicated to the preservation of the Earth’s ecological resources, sued the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the U.S. Department of the Interior over the “Final Rule” delisting the gray wolf. While not the primary motivator for this lawsuit, the premature hunting season shocked many Americans. Most of the news media at the time came out against the cull, highlighting the threat of extinction if such hunts continued. In line with most media, one argument made by the plaintiffs claimed that the USFWS “improperly relied on inadequate and outdated state plans for gray wolf management” when deciding to delist gray wolves both in and out of the Western Great Lakes DPS. 32 However, the Court found the Service’s management plans to be sufficient and denied these claims. Thus, the threat of extinction after delisting was not the primary focus of the lawsuit. Rather, the suit highlighted both how the Service inadequately accounted for the loss of the gray wolf ’s historical range and how it based a delisting argument on an insufficient statutory definition. Thus, the battle did not concern a determination of whether the gray wolf species would survive without protections, instead focusing on how the Service failed to provide sufficient reasoning to delist the species in the first place. The suit claimed the agency skipped steps and blindly jumped into loopholes instead of performing suitable analysis to back these claims. The Service’s claims appeared rushed, and many groups of wolf-advocates suggested ulterior motives due to this observation.

Image by Rain Carnation from Pixabay

The District Court of the Northern District of California found that the USFWS’s use of statutory definitions of “species” to delist was dangerous, as Congress did not intend for these amendments “to remove protections for already-listed entities.” 33 After reviewing that section of the “Final Rule,” the Court concluded that the argument was a type of “statutory dodge.” 34 The USFWS had already made similar attempts before, trying to designate and delist distinct population segments of gray wolves in 2007 and 2014. This conclusion highlights the Service’s underhanded methods of delisting species, illuminating the ulterior political motives that may have driven this effort. The Service even tried to “ask the Court to disregard this analysis as unnecessary to its determination,” urging the court to redress this mistake. 35 The request was denied.

The plaintiffs’ next argument focused on the USFWS’s failure to analyze gray wolves across the entire lower 48 states. They contended that the USFWS based its decision on “the purported recovery of wolves in the [Western] Great Lakes and Northern Rocky Mountains.” 36 Plaintiffs stated that the actions of the Service here were no different from previous attempts to delist the gray wolf. Each time, the USFWS’s attempts failed because it focused solely on the larger meta-population of wolves, claiming their recovery reflected the entirety of the species. Specifically, the Courts looked closely at the West Coast wolves, previously listed as endangered, to determine whether there was adequate reasonable explanation for removal of protections. The 2020 rule claimed the genetic similarities between the West Coast and NRM wolves warranted their delisting, as the NRM wolves could support their population. However, the studies that the USFWS relied on to make its claims of genetic similarity also noted that “wolves with coastal ancestry ‘should be considered a priority for conservation given their unique evolutionary heritage and adaptations.’” 37 Despite these genetic similarities, the USFWS decided to ignore this statement when writing its Final Rule, further illuminating its hasty and messy claims. The Court said the USFWS’s decision to combine these DPSs was “arbitrary and capricious,” granting victory to the defenders of the wolves.

Furthermore, the plaintiffs challenged the USFWS’s interpretation of the phrase “significant portion of its range” 38 in reference to the gray wolf’s historical range. In order to delist a species, the Service must determine if it is “no longer threatened or endangered throughout all or a significant portion of its range.” 39 The Endangered Species Act still does not define this phrase, keeping it “inherently ambiguous.” 40 The USFWS tried to define it in 2014 but failed to do so. In that light, the Service explains in the Proposed Rule, the public draft before the Final Rule delisting wolves, how it has not officially determined the meaning of the phrase, but it “assessed ‘significant’ based on whether portions of the range contribute meaningfully to resiliency, redundancy, or representation of the gray wolf entity being evaluated without prescribing a specific ’threshold.’” 41 Basically, the decision to determine whether the population was significant was at the discretion of the Service, with the Service permitted to argue for “any reasonable definition of ‘significant.’” 42 With a standard this flexible, there is no objective measure that can be used to define what is a “significant portion” of the wolves’ former range. For example, the Final Rule states that the NRM and West Coast states’ wolves could add to the resiliency, redundancy, and representation of the species. 43 But in another part of the Rule, it concludes that wolves in these portions of the range are not significant to the redundancy or resiliency of the species as they occur in small numbers, having relatively few breeding pairs. 44 Since it could not be defined, the Court found the phrase superfluous, which helped poke more holes in the validity of the “Final Rule.”

Image by 942784 from Pixabay

The plaintiff’s last objection noted the USFWS’s failure to evaluate the impact of the loss of the gray wolf’s historical range. Plainly, the Court stated, “the Final Rule fails to adequately grapple with the causes and effects of historical range loss.” 45 The Service argued that analyzing “the threat of human-caused mortality” was sufficient enough to wrestle with the loss of historical range, since human-threat was the primary cause for it. 46 Moreover, the Service supported its argument by adding that since there are state laws already in place to protect wolves and that no active “eradication” program exists in their “current” range, “lost historical range does not threaten the species with extinction.” 47 However, the Courts found that the analysis the USFWS referenced only accounted for the human-threat in the gray wolf’s “current” range, which covers only 15 percent of the historical range. 48 Primarily, the Service didn’t adequately address the impact of this significant loss in historical range and its “possible enduring consequences” for the gray wolf. 49 Thus, for all these reasons, the Court found this rule unlawful and vacated it. On February 10, 2022, wolves won again, gaining back their previous protections.

Conclusion

Seventy-four percent of scientists working for the USFWS believed that political interests were too influential in the making of policy and regulation decisions. 50 The numerous failed attempts by the USFWS to delist wolves suggests political rather than scientific motives, especially considering the Service’s consistent failure to adequately analyze the gray wolf’s historical range. In addition, public opinion around wolf conservation has been favorable. A 2014 survey study found 61 percent of respondents had a positive attitude towards wolf conservation. 51 Another recent study found that Colorado residents felt positively about wolf reintroduction and conservation. 52 To further these findings, a 2021 study about politics and attitudes toward wolves noted that political affiliation strongly impacted opinions about wolf conservation and management. 53 They found that Democrats consistently held positive views of wolf conservation while all other political categories had no notable positive or negative views. 54 Another study found that in some specific areas of the country, political affiliation can actually determine perceptions on wolves, specifically identifying the Pacific Northwest as one of these areas. 55 In aggregate, these studies suggest that wolf management has become a partisan issue. Because USFWS scientists believe the agency is heavily influenced by politics, and considering the aforementioned studies, these findings suggest connections between political affiliation and perceptions towards wolves. Whether these affiliations influence the USFWS decision is unclear.

Rural communities and ranchers directly impacted by wolf management policies are more likely to hold negative attitudes toward wolves. 56 Concerns about the potential danger to people and pets posed by wolves, the loss of hunting opportunities due to wolf predation, and potential wolf predation on livestock, all mean that wolf management legislation can directly impact rural communities. 57 Opponents of wolf protection frequently cite livestock losses in media reports concerning wolf management. The economic threat to rural livelihood through these losses motivates much legislation against wolf conservation. However, these concerns may be anecdotal, as research show wolves have little impact on livestock loss.

In 2019, for instance, the Humane Society investigated the reported numbers of cattle and sheep deaths due to wolves in the United States. Interestingly, the Society found stark differences between the statistics published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture-Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA-APHIS) and the USFWS. For instance, the USDA claims wolves killed 4,360 cattle in 2015, while the USFWS verified only 161 losses. 58 According to the Humane Society, the USDA collected its data from a few, mostly unverified sources, “which the USDA then extrapolated statewide without calculating standard errors or using models to test relationships among various mortality factors.” 59 USDA’s methods suggest it exaggerated livestock losses due to wolves, folding losses to all “native carnivores and dogs” into the total and inflating statistics far beyond predation solely due to wolves. 60 Such misinformation informs public policy, “including helping to fuel countless legislative attacks on wolves… and the Endangered Species Act by Congress.” 61

Astoundingly, even if the USDA’s wolf-predation statistics are given credence, the numbers pale in comparison to other causes of livestock loss. The USDA reported that in 2017 cattle and sheep killed by wolves only make up one percent of unwanted livestock deaths per state. 62 Most unwanted livestock losses are due to “health, weather, theft and birthing problems.” 63 Moreover, it also reported that domestic dogs kill “100 percent more cattle than wolves and 1,924 percent more sheep.” 64 Thus, at best, even if the USDA’s statistics were correct, predation due specifically to wolves has a negligible impact on livestock.

As the proposal for delisting all wolves from the ESA was published on election day, it was one of the last regulatory measures the Trump administration enacted before the end of his term. However, even before this rule, the administration rolled back numerous environmental regulations, including making many changes to the ESA to weaken it, making delisting easier. One of these changes removed the phrase “without reference to possible economic or other impacts of such determination,” in reference to any decision made under the ESA. 65 This introduced economic and “other impacts” in determining whether a species qualified to be listed. Moreover, the Service removed the practice of providing a future “threatened” species with the same protections as endangered species automatically, requiring that the protections to be determined by the species’ conservation needs. 66 Due to the ESA defining “threatened” status as “any species that is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range,” this would require the USFWS to explain the extent of these threats in the “foreseeable future” as probable. 67 In essence, these changes would make it more difficult to list future species, allow them to keep their protections, and make delisting easier by drawing more attention to the economic impacts of protecting a species. All the while, the Trump administration argued its incentive to “loosen regulations” was to reduce “the regulatory burden on the American people” while “providing the best conservation results.” 68 The administration saw these changes as positive, while many critics and conservation groups said these revisions would “make it harder for the US government to safeguard a species that is found across a wide range of the country” and, furthermore, “handcuff regulators from protecting wildlife from the climate crisis.” 69 While not concrete evidence, the trend in legislation on environmental policies predating the delisting of the gray wolf illuminates possible political influence threatening wolves’ protections.

Following the re-listing of the American gray wolf, multiple unhappy parties filed appeals which were in mediation until February 26, 2023. On that day, the Circuit Mediator of the Appeals Court ordered a temporary stay on appeals until February 2, 2024, for administrative purposes. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service intends to submit another proposed rule concerning the listing status of the gray wolf in the lower 48 states when the stay lifts.

70 If history repeats itself, most likely another effort will be made to delist the gray wolf. Only time will tell whether the next ruling will favor them.

Image by Angela from Pixabay

1 Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. “Wisconsin DNR Announces Wolf Season Begins Nov. 6, 2021.” https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/newsroom/release/39871. Accessed May 15 2023.

2 Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Bureau of Wildlife Management.

3 “Hunter Nation V. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.” Case No. 21CV31, United States Circuit Court for Jefferson County, Wisconsin, 2021. https://will-law.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Hunter-Nation-SJ-Decision.pdf.

4 Defenders of Wildlife. “Fall 2021 Wolf Harvest Season Comments.” 2021. https://defenders.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/DefendersOfWildlife_Comments_NRB_meeting_2021.pdf.

5 Johnson, Randy and Anna Schneider. “Wisconsin Wolf Season Report.” edited by Wisconsin Department of Natural Resoruces, 2021, pp. 1-9. https://widnr.widen.net/s/k8vtcgjwkf/wolf-season-report-february-2021.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Hubbuch, Chris. “Wolf Hunters Vastly Exceed Wisconsin Quota in First Hunt since Federal Protections Dropped.” Wisconsin State Journal, 2021. https://madison.com/wsj/news/local/environment/wolf-hunters-vastly-exceed-wisconsin-quota-in-first-hunt-since-federal-protections-dropped/article_47537484-7cf6-56d6-bd0f-21d0a0b4a76e.html//.

10 Clemons, Alan. “Wisconsin Hunters Take 216 Wolves and Exceed Harvest Quota in Controversial Hunt That Closed after Just Three Days.” Outdoor Life, 2021. https://www.outdoorlife.com/story/hunting/wisconsin-wolf-hunt-exceeds-harvest-quota/.

11 Johnson, Randy and Anna Schneider. “Wisconsin Wolf Season Report.” edited by Wisconsin Department of Natural Resoruces, 2021, pp. 1-9. https://widnr.widen.net/s/k8vtcgjwkf/wolf-season-report-february-2021.

12 Learn, Joshua Rapp. “The ESA Fails Due to Slow Listing Process.” https://wildlife.org/the-esa-fails-due-to-slow-listing-process/. Accessed April 1 2023.

13 Hoffman, Austin and Annie White. “Brief History of Wild Wolves.” Mission:Wolf. https://missionwolf.org/brief-history-of-wolves-in-the-wild. Accessed April 1 2023.

14 “America’s Gray Wolves: A Long Road to Recovery.” Center for Biological Diversity. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/gray_wolves/. Accessed April 1 2023.

15 White, Annie B. “A History of Wild Wolves in the United States.” Gray Wolf Conservation. https://www.graywolfconservation.com/Wild_Wolves/history.htm#:~:text=It%20is%20estimated%20that%20over,over%20the%20past%2050%20years. Accessed April 1 2023.

16 Ibid.

17 “Endangered Species Act of 1973 as Amended through the 108th Congress.” 16 USC §1531-1544, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, December 28, 1973 pp. 1-41.

18 Ibid.

19 United States, Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service,. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Removing the Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) from the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife.” 85 FR 69778, Federal Register, 2020, pp. 69778-895. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-11-03/pdf/2020-24171.pdf#page=1.

20 Union of Concerned Scientists. “Progress and Problems: Government Scientists Report on Scientific Integrity at Four Agencies.” 2015. https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/attach/2015/10/ucs-scientist-survey-2015-appendix-b.pdf.

21 United States, Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service,. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Removing the Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) from the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife.” 85 FR 69778, Federal Register, 2020, pp. 69778-895. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-11-03/pdf/2020-24171.pdf#page=1.

22 Ibid.

23 “Endangered Species Act of 1973.” Public Law 93-205 87 Stat., December 28, 1973 pp. 884-903. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-87/pdf/STATUTE-87-Pg884.pdf.

24 “Endangered Species Act of 1973 as Amended through the 108th Congress.” 16 USC §1531-1544, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, December 28, 1973 pp. 1-41.

25 Chaffetz, Mark. “Clarifying the Endangered Species Act’s ‘Distinct Population Segment’ Policy through the Lens of Grizzly Bears.” Virginia Environmental Law Journal, 2019, http://www.velj.org/elrs/clarifying-the-endangered-species-acts-distinct-population-segment-policy-through-the-lens-of-grizzly-bears#_ftn2.

26 United States, Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Removing the Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) from the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife.” 85 FR 69778, Federal Register, 2020, pp. 69778-895. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-11-03/pdf/2020-24171.pdf#page=1.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid.

32 “Defenders of Wildlife V. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,.” 4:21-cv-00344-JSW, United States Disctrict Court of the Northern District of California, 2022. https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/AG/releases/2022/February/Wolf_Delisting_Order_747978_7.pdf?rev=3e04211d990d4d458025d58d49ea1f68.

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid.

40 Ibid.

41 United States, Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service,. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Removing the Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) from the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife.” 85 FR 69778, Federal Register, 2020, pp. 69778-895. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-11-03/pdf/2020-24171.pdf#page=1.

42 “Defenders of Wildlife V. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,.” 4:21-cv-00344-JSW, United States Disctrict Court of the Northern District of California, 2022. https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/AG/releases/2022/February/Wolf_Delisting_Order_747978_7.pdf?rev=3e04211d990d4d458025d58d49ea1f68.

43 United States, Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service,. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Removing the Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) from the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife.” 85 FR 69778, Federal Register, 2020, pp. 69778-895. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-11-03/pdf/2020-24171.pdf#page=1.

44 “Defenders of Wildlife V. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,.” 4:21-cv-00344-JSW, United States Disctrict Court of the Northern District of California, 2022. https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/AG/releases/2022/February/Wolf_Delisting_Order_747978_7.pdf?rev=3e04211d990d4d458025d58d49ea1f68.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 “America’s Gray Wolves: A Long Road to Recovery.” Center for Biological Diversity. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/gray_wolves/. Accessed April 1 2023.

49 “Defenders of Wildlife V. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,.” 4:21-cv-00344-JSW, United States Disctrict Court of the Northern District of California, 2022. https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/AG/releases/2022/February/Wolf_Delisting_Order_747978_7.pdf?rev=3e04211d990d4d458025d58d49ea1f68.

50 Union of Concerned Scientists. “Progress and Problems: Government Scientists Report on Scientific Integrity at Four Agencies.” 2015. https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/attach/2015/10/ucs-scientist-survey-2015-appendix-b.pdf.

51 Hamilton, Lawrence C. et al. “Wolves Are Back: Sociopolitical Identity and Opinions on Management of Canis lupus.” Conservation Science and Pratice, 2020, pp. 1-13, doi:10.1111/csp2.213.

52 Niemiec, Rebecca et al. “Public Perspective and Media Reporting of Wolf Reintroduction in Colorado.” PeerJ, no. 8:e9074, 2020, doi:10.7717/peerj.9074.

53 Eeden, Lily M. van et al. “Political Affiliation Predicts Public Attitudes toward Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) Conservation and Management.” Conservation Science and Pratice, vol. 3, no. 3, 2021, doi:10.1111/csp2.387.

54 Ibid.

55 Hamilton, Lawrence C. et al. “Wolves Are Back: Sociopolitical Identity and Opinions on Management of Canis Lupus.” Ibid.2020, pp. 1-13, doi:10.1111/csp2.213.

56 Eeden, Lily M. van et al. “Political Affiliation Predicts Public Attitudes toward Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) Conservation and Management.” Ibid.vol. 3, no. 3, 2021, doi:10.1111/csp2.387.

57 Niemiec, Rebecca et al. “Public Perspecgive and Media Reporting of Wolf Reintroduction in Colorado.” PeerJ, no. 8:e9074, 2020, doi:10.7717/peerj.9074.

58 The Humane Society of the United States. “Government Data Confirms That Wolves Have a Negligible Effect on U.S. Cattle & Sheep Industries.” 2019, pp. 1-30. https://www.humanesociety.org/sites/default/files/docs/HSUS-Wolf-Livestock-6.Mar_.19Final.pdf.

59 Ibid.

60 Ibid.

61 Ibid.

62 USDA-Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. “Death Loss in U.S. Cattle and Calbes Due to Predator and Nonpredator Causes, 2015.” 2017. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/general/downloads/cattle_calves_deathloss_2015.pdf.

63 The Humane Society of the United States. “Government Data Confirms That Wolves Have a Negligible Effect on U.S. Cattle & Sheep Industries.” 2019, pp. 1-30. https://www.humanesociety.org/sites/default/files/docs/HSUS-Wolf-Livestock-6.Mar_.19Final.pdf.

64 Ibid.

65 United States, Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service,. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Revision of the Regulations for Listing Species and Designating Critical Habitat.” 83 FR 35193, 2018, pp. 35193-201. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-07-25/pdf/2018-15810.pdf.

66 Ibid.

67 “Endangered Species Act of 1973 as Amended through the 108th Congress.” 16 USC §1531-1544, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, December 28, 1973 pp. 1-41.

68 Stracqualursi, Veronica.

69 Holden, Emily. “Trump Officials Weaken Protectiosn for Animnals near Extinction.” The Guardian, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/aug/12/endangered-species-act-trump-administration-protection-changes.

70 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Statement on the Gray Wolf in the Lower-48 United States.” 2023. https://www.fws.gov/media/2023-usfws-gray-wolf-statement.