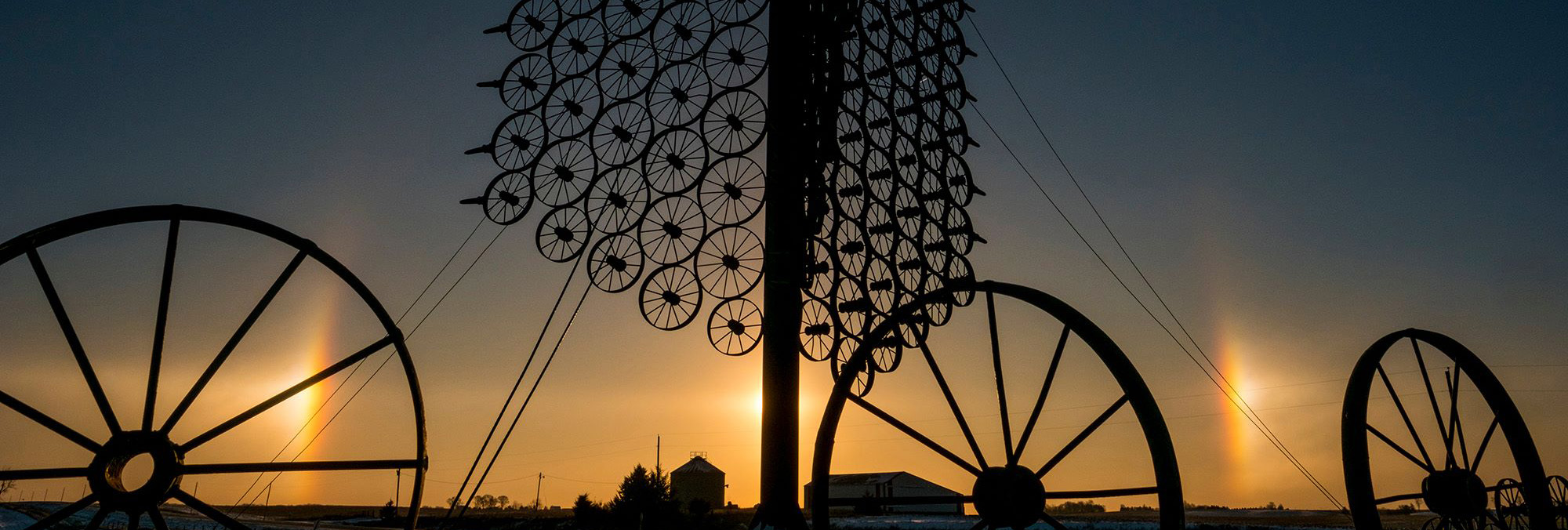

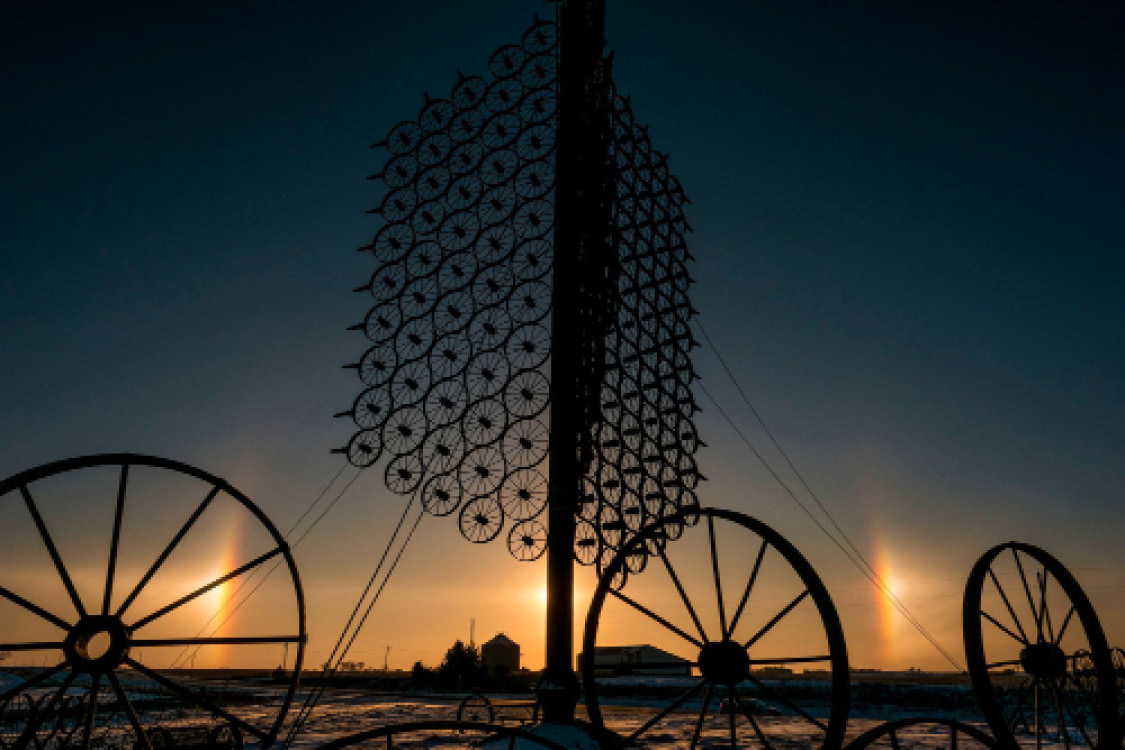

The photographs on the facing page and the page following are of a sundog, or rather of two sundogs, which flank the sun in the middle. Sundogs are an atmospheric oddity with many of the same original characteristics of a rainbow. A spectacular phenomenon, they are caused by hexagonal prism-shaped ice crystals in the upper atmosphere. 1

Sundogs flanking L. J. Maasdam’s wheel sculpture outside Sully, Iowa. Photo by Justin Hayworth

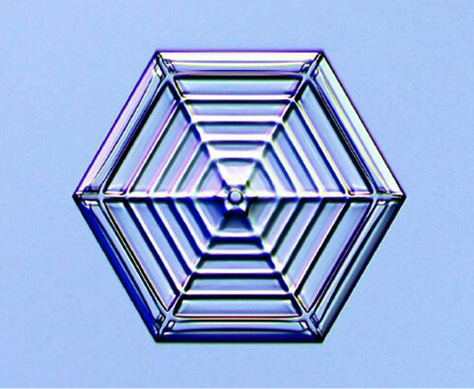

Microscopic hexagonal prisms of ice (see the photograph, at right) work together to diffract the light of the sun at precise angles across a horizon. The ring connecting the two sundogs in the photographs is created by similar crystals that have a longer height. Acting together, these crystals produce a halo effect around the sun that follows alongside just like a pair of loyal dogs. 2

Sundogs form when light diffracts through hexagonal ice crystals in the upper atmosphere. Photo by Kenneth Libbrecht, California Institute of Technology

The things that set sundogs apart from rainbows can be ascribed to a couple of factors. First, in contrast to a rainbow, the arcs appear separated from the sun at precise 22-degree arcs on either side of it. This means that unless one has a habit of looking directly at or around the sun, sundogs can be tricky to catch. Secondly, the crystals essential for the creation of these phenomena are only formed at low temperatures and under specific climate conditions. The long winters of the prairie region, combined with the flat, uninterrupted horizon, make for a perfect harmony that allowed Grinnell College’s campus photographer, Justin Hayworth, to take the beautiful photographs you see here.

The origin of the word “Sundog” is hotly debated. Most linguists agree that the name has roots in mythology. Norse mythology makes reference to the term Solhunde or Solvarg, both meaning, essentially, “Sun Dog.” However, the scientific terminology for the phenomenon is parhelion, which is derived from the Ancient Greek meaning “beside the sun.” Aristotle is quoted as saying, “two mock suns rose with the sun and followed it all through the day until sunset.”

3 Aristotle follows this with the statement, “mock suns” are always to the side, never above or below, most commonly at sunrise or sunset, more rarely in the middle of the day." This could indicate that at the time Aristotle was writing, no common name yet existed. Aristotle was describing the event rather than simply offering a name. Aristotle isn’t the only noteworthy historical figure to discuss Sundogs, as William Shakespeare also makes reference to sundogs in the third part of his play King Henry VI.

Sundogs over an Iowa farmstead. Photo by Justin Hayworth

Three glorious suns, each one a perfect sun;

Not separated with the racking clouds,

But sever’d in a pale clear-shining sky.

See, see! they join, embrace, and seem to kiss,

As if they vow’d some league inviolable:

Now are they but one lamp, one light, one sun.

In this the heaven figures some event.

Act Two, Scene One

Henry VI, Part 3

William Shakespeare

1 “Cloud Crystals and Halos, Atmospheric Optics UK,” https://atoptics.co.uk/halo/crhal.htm

2 “What Causes Halos, Sundogs and Sun Pillars?,” National Weather Service, 2006, https://www.weather.gov/arx/why_halos_sundogs_pillars

3 Aristotle, Meteorologica (340 B.C.E.)