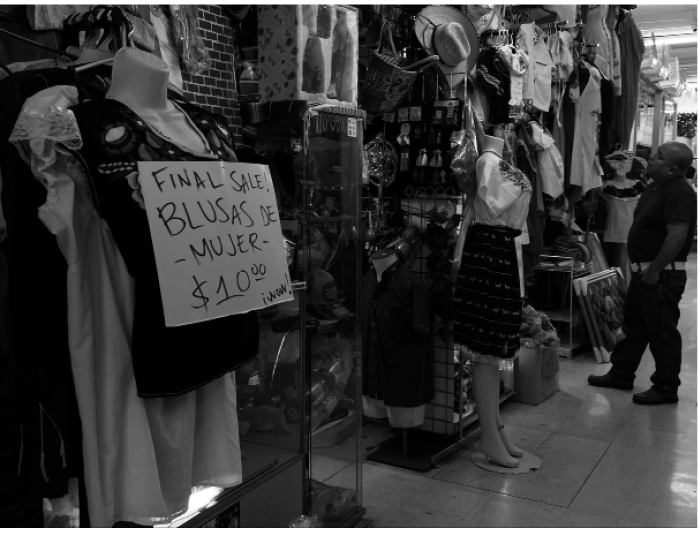

Little Village, a predominantly Mexican community located near the “Heart” of Chicago, recently lost one of its significant cultural roots. The Discount Mall, or “El Mall de veintisies,” as locals would call it since it sits along 26th Street, recently kicked out half of its vendors due to Novak Construction, a major contractor, buying the plaza in which the mall is located. While the community rallied and pleaded with lawmakers and the company itself, all they were able to achieve was to delay the eviction date by a few months. Ultimately, after 31 years of business, the majority of vendors had to pack their bags and abandon what many of them had come to call their business home.

The Discount Mall has fostered a strong sense of community and encapsulates the culture of Little Village. When people think of Little Village, the Mexican culture stands out the most. However, what is “Mexican” culture? It’s the food. It’s the music. It’s the hard-working people. It’s the resilience, that even after being beat down day in and day out, you are still going home to your family with love. It’s the family values that we hold near and dear to our hearts.

Due to the way contracts work at the mall, many of the vendors went under; there are two owners, for neither of whom was I able to receive any contact information. Both were given contracts to keep some percentage of their buildings respectively. The mall was one big building with doors in the middle dividing the left and right side. Each owner owned one half of the mall. Granted, no matter if they signed on or not, there was going to be some downsizing, but one of the owners refused to, which left him and the vendors under his contract without a place for business.

Novak Construction has announced plans for the future of the mall. This entails the laying off the majority of the vendors and bringing in larger commercial stores to the plaza. While it may be good for business, it defeats the purpose of the plaza, which, beyond its commercial purpose, is creating community strongly rooted in the Mexican culture of Little Village. It is gentrification in front of our own eyes.

I wanted to take a deeper dive and ask the vendors and customers who make the Discount Mall the pillar of culture for their perspective. Major news outlets only mention the closure briefly. I wanted the story—their story. I had the opportunity to interview three vendors with staple businesses within the mall, as well as with community member. These are their stories.

A Vendor: Trajes*

I interviewed a vendor who is keeping their shop open even after all the chaos that Novak brought to the community. For the sake of their business, they have requested to remain anonymous. They immigrated from Mexico at the age of 15 and were presented with a job opportunity at a clothing store in Little Village, at their sister location at the Mall, where they’ve been for 20 years now.

“It was after the pandemic that I knew Novak bought the mall.…Things between the vendors haven’t been the same since this news. We’ve limited the amount of merchandise we would usually get, we would live with the fear of losing our jobs that we’ve worked so hard to keep for more than 20 years.”

This is the first time I got a clear timeline regarding the announcement of closings; it comes as a shock that a company would come in and take people’s livelihoods from them, but even more so after a devastating pandemic. As this vendor goes on to say, Novak’s actions changed the behavior even of businesses that were not evicted. When I visited the Mall, there wasn’t the same lively atmosphere, the shops weren’t popping and everything seemed to be much more conservative, and I now know why. These vendors knew that their shops might not make it, and while they cling to faith, it’s better to be pleasantly surprised than to be disappointed. They brace for the worst by having less merchandise and expect to sell what they have and move on to whatever may be next.

Every day for them felt like an uphill battle, and maybe today would be the day they get the call that they have to pack. Maybe it’s the day they see the bulldozer outside their workplace. Or maybe today would be the day they longed for, when the owners or even the alderman came in with a contract, informing them that eviction was avoided. However, for more than half the vendors the worst has already happened: they lost not just their jobs, but also their life’s work with nothing more than a memory to show for it, just a memory.

Trajes told me:“Discount Mall is more than just an experience, it’s a state of mind.” It’s a very small quote, but it carries so much weight. While many, including me, would walk in and spend a Sunday with the family at the Discount Mall, grab an elote and maybe even buy something, it was when I walked in in March of this year that something had vastly changed. Something was missing, and while I couldn’t put my finger on it at the time, I realize now that the passion had left. Everyone seemed beaten down and distraught at the prospect of losing their shops, their lives. There wasn’t a fight there anymore. Some vendors shared feelings of frustration, others shared feelings of sadness, but they all expressed love for the Mall. However, they have all accepted the inevitable - not because they wanted to, they were just exhausted.

*“Trajes” is an alias used to preserve the vendor’s anonymity.

Maricela Iñiquez: Iñiquez Unisex Hair Salon

Originally from Mexico, but naturalized in the States, Maricela Iñiquez is a professional hair stylist who has been working for more than thirty years, starting when she was still a sophomore in high school, balancing both high and cosmetology school. The years of training paid off quickly since she opened her shop at the Discount Mall when it first opened in 1991. She shares her story full of a mixture of emotions: opportunity, faith, and hope, but at the same time frustration and disappointment for the place that has given her so much ends so abruptly.

Maricela Iñiquez says: “Tenemos 30 años trabajando. Dia a dia. Se mira simple, humilde, sace mis dos hijos. Sace carreras de aqui. Por la bendición de este hogar” Translation: “We have 30 years working here; - day to day. It looks simple, humble even. I got my two kids through life with this, I made careers here. Because this place is a blessing we call home.” ~ Maricela Iñiquez

It’s been thirty years of business for her. It’s no longer just a “job” for her, it’s her life. While vendors such as Maricela may live as much as an hour away, the mall is where their friends are, where they watched their kids run around, get dirty, and grow up. Maricela feels all of this, but in addition to the sadness and frustration, she, along with many other vendors, calls this place a blessing. It has given them more fruit than any tree, and more shade than any umbrella. She has had numerous people come to work for her, and now her ex-employees run their own hair salons in Mexico, Uruguay, and Argentina. She, along with the other vendors, know that this mall isn’t as grand as the Mall of America, nor is it trendy like malls downtown. It’s simple, but it’s rooted.

Maricela Iñiquez said “No sace ni un cinco de el gobierno, ni para mis hijos. No estamos pidiendo, estamos trabajando. Están cortando el corazón de Chicago, pero yo estoy riendo y bailando con la muerte porque sin nosotros no tienen nada.” Translation: “I’ve never accepted a single dollar from the government, not even for my children. We’re not begging, we’re working. They’re cutting the heart of Chicago, but I’m laughing and dancing with death because without us you’re nothing.”

Maricela’s statement is directed at Novak Construction, the buyers of the mall, and at the American capitalist system in general. Maricela emphasizes that the vendors are hardworking people who must pay rent on a weekly basis. If they do not sell a certain amount, they’re evicted. Despite these constraints, they take pride in their work. It’s not a side hustle for them; it’s their livelihood—they keep their families alive with this money. This is often overlooked by Novak and anyone else who looks at this building as a source of profit.

When Maricela refers to the “heart,” what she means is that the mall is located close to an area known as the “Heart of Chicago.” This location is the reason Novak Construction was tempted to buy out the mall. For Chicago, Little Village is a gold mine; known as the Second Magnificent Mile, it brings in around $900 million annually. Yet these businesses are run by forgotten people who don’t need fancy stores or skyscrapers, to generate big revenue, just hard work and a spirit rooted in community and culture. When Novak Construction buys the mall to pursue only economic gain, they are seen by the vendors as a symbol of death, bringing the end of an aspect of the community that is beloved. While many people, from vendors to community members, are scared or even furious about the future of the mall. Maricela isn’t fazed, but rather laughs at Novak because she knows that without the vendors, the community, the people, the plaza is nothing. This “dance” that she refers to is a nod to traditions in Latin culture, where dances often symbolize a new beginning or an ending to something great.

Maricela Iñiquez says “El hombre que trabaja tiene honor, tiene vida. El hombre que no trabaja no tiene nada y los que ni quieren trabajar tienen menos, y por eso cortarle el pescuezo. Y aqui esta mío, cortamelo porque yo tengo todo.” Translation: “The man that works has honor, he has life. The man that doesn’t work has nothing, and those who don’t even want to work have less, and because of that, cut off their [Novak] necks. And here’s my neck, for I have everything.”

Maricela’s statement is directed at Novak. Honor is one of the most valued qualities in a person within Mexican culture. To earn honor, one must work, get their hands dirty, so that they can say that what they accomplished or made is by their own labor. Since Novak and its people only signed a check to earn the mall, she labels them as people without any honor. It’s the injustice of the capitalistic system, in which the person with money can swoop in and buy out a place of great significance, purely for financial gain.

Los Esteros: A husband and wife duo

One of the most well-known vendors in the mall is a husband-and-wife duo that sells stereos. Anyone who has spent time at the mall remembers walking near the south end of the mall to be greeted by flashing LED lights and heavy bass-boosted Mexican music. It’s a very popular and vivid stand, one that cannot go unmentioned when the Discount Mall is brought up. They too shared their story but preferred to remain anonymous.

The wife said: “Me gusta estar aquí, me gusta mi trabajo, me gusta la comunidad, me gusta platicar cuando la gente viene de afuera.” Translation: “I like being here, I like my job, I like the community, I like to talk with people that come from afar.”

It’s a sentiment shared by many vendors. They are not forced to take this job, nor are they wishing for another job. These people know that life might be hard financially, but they do not care. This is because the mall connects back to the community, and they like, even love, the community. “Community” in this case can be understood in two ways: the community of Little Village and the community within the mall itself. The Discount Mall gathers people from everywhere who are connected through culture, something so rare and beautiful, but it’s still being stripped away.

The wife says: “Nos supimos por la noticas que se iba vender el mall.” Translation: “We found out through the news that they were going to sell the mall.”

The harsh, unfortunatel reality is that the vendors were denied the respect they deserved by not being told the news of the mall being bought out to their face. Instead, many found out about the eviction from the television news. This was a major slap in the face for these people, and they were still left in the dark when they posed questions about their future. The husband-and-wife shop owners told me that they had reached out to their alderman at the time but heard nothing back. They also reached out to their mall landlord and again heard nothing. No one was willing to talk, and they were left confused and scared.

The husband says: “Yo digo, yo de aquí digo. No tengo otro trabajo. Toda mi vida he estado aquí trabajando y manteniendo de aquí mis hijos, mi casa, mi familia. Se me hace injusto que no nos permitan quedarnos.” Translation: “I’ll say it right here, I have no other job. All my life I have worked here, and I have maintained my kids, my house, and my family afloat through this job. I think it’s unjust that they don’t let us stay.”

Everyone who is impacted by the mall’s closure has said similar things. They don’t know what’s next. This was their only source of income, their literal life’s work. For this couple, this is all they know. The husband began to work at the stereo shop as a high schooler, and he later took the opportunity to run the shop. His wife soon joined, and this has been their life ever since.

The people who buy out this mall seem not to care that this impacts entire families and communities. It won’t just be the vendor being hurt by the closing. It’s also their children that are dependent on them. It’s also the family down the block that makes visiting the mall their weekly family activity.

Morelia Bermudez: a community member

Morelia Bermudez grew up within the community, developed strong ties within it, and has been a part of the Discount Mall in multiple ways, both through relations with vendors and by being a vendor herself when she was younger, she now attends the University of Illinois in Chicago UIC but remains rooted in her community. She shares her thoughts on the mall closing.

“My aunt had a candy shop, it was fun and nice to see people appreciate something as small as candy, and it brought people together. And another friend had a shop of trajes (dresses).”

Morelia went to the mall every weekend growing up. She helped her aunt with her shop, and it showed her the joy of candy. She reminisces about how happy older people got when they saw candy from their childhoods back in Mexico. This small, sugary thing brought them back every week, asking for more. She also refers to a close friend and their family business of trajes. Trajes are dresses and outfits for any occasion. However, in Latin-American culture it is deeply rooted in some of our biggest life achievements. Typically the first time someone wears one is in their Baptism: the boys wear a white suit and the girls a white dress. This later carries onto other religious achievements such as The First Communion and Confirmation. But the biggest reason that people buy these trajes is for a girl’s Quinceañera, when a girl enters adulthood in Latin American culture.

“They jumped through hoops just to sell, and they did it with so much happiness while knowing that the money wasn’t reliable,” says Morelia. “I admire these people, they’re working hard day in and day out, but they stayed. They were the backbone to what made Little Village, Little Village.”

Here Morelia is referring towhat is needed to sell in the mall. While it may seem that all you need is to fill out an application, that’s far from the truth. Each vendor needs to secure a license, negotiate with the landlord, and on top of that pay the weekly rent. The key part in all of this is that income to pay the rent is not guaranteed, and these vendors knew that. However, they do their work with a smile on their face because this is their very own business. Many think these people did research and knew that money will pour in, but that just isn’t the case. They’re selling for their livelihoods, but they also know that they won’t become rich. This is a passion of theirs.

The second part of the quote really shows how the community views these people. All of this you find in every vendor. These vendors are the embodiment of Mexican culture, from the work ethic to the high value they place on their families and community. The vendors made the mall into a haven for all of us to enjoy.

There’s a saying that I grew up with, one that my father said was common back home in Michoacan: “Todo a su debido tiempo,” or, “everything in due time.” I look at the photographs I took of the mall. The vendors knew above all that it was time to go. Shortly after these interviews were conducted, the contracts expired, and most vendors were kicked out. While it was abrupt and not the ending they were hoping for—one where they have the power to call their last ever sale—it was the end nonetheless. They overcame numerous obstacles and struggles to come to where they are now, and this is nothing more than just that, an obstacle. With plans to relocate the vendors to a new location, there is still a sliver of hope that these vendors cling onto. It’s the fire that will ignite again that will get them through this because that is what they all share. A fire to keep going. Currently, the plaza is under construction, and while the plans may look aesthetically pleasing, it is now a shell of what was once there.