On the last day of March 2023, I was able to interview my older brother, Peter Chan Min Sang, about his experience working as an ESL teacher, with immigrant and refugee students in St. Paul, Minnesota. I recognized that my brother was in a unique position because many of his students—most of whom are Karen people—are also from Myanmar/Burma. In this interview, we talked about the histories and experiences that led the Karen people, as well as Peter, to the land of 10,000 lakes.

Myanmar/Burma is a heterogeneous country with more than 135 ethnic groups, who are assigned to seven states and divisions administratively. My family belongs to one of the smaller ethnic groups, the Chin, who traditionally reside along the northeastern mountains of Myanmar/Burma, near India and Bangladesh. The Karen people are constitutionally given a state at the western borders of Myanmar/Burma, next to Thailand. Despite the distance between the Karen and the Chin States, our ethnic communities live close to one another in Yangon, the largest city of Myanmar/Burma, where my brother and I grew up.

On February 1st of 2021, the military took over the central government of Myanmar/Burma in a coup d’état. Since then, the civil war in our country has become more violent and devastating. Many more people have begun to seek for asylum in neighboring countries, hoping to find better lives elsewhere in the world. However, this interview taught me that the refugees who end up in the first world still struggle to thrive due to language and culture barriers.

SCHS: Could you introduce yourself?

PCMS: My name is Peter Chan Min Sang. Currently, I teach English as a second language to mostly immigrant students at a high school in St. Paul. I’ve been doing this for four years. I was born and raised in Myanmar/Burma. I came to the United States in 2013 for college. I went back home to teach for a year before I came back here in 2018. I did my Master’s in teaching at the University of Minnesota. I’ve been teaching in the St. Paul Public Schools since then.

SCHS: Let’s start way back. Could you tell me about your early experience of education?

PCMS: I went to a public school in [Insein township in] Yangon. It’s a government-run Kindergarten to Eighth Grade school. It’s a bit outside of the city, but it’s still a decent sized school. I think there were about 2,000 students. It’s a very, I want to say, traditional Burmese school. We had a uniform that was white and green.

SCHS: I also attended that school. And what I remember is that a lot of our schoolmates were, in a sense, immigrants to the lowland because a lot of them are Karen [people].

PCMS: [The Karen people whom we grew up with] are actually from the [Irrawaddy River] Delta. There’s a huge Karen population in the Delta.

SCHS: I did not know that. I think that there is something to be critical about assigning certain land to an ethnic group. Because that gives a false perception that the people that live on that land will only be from that ethnic community or that an ethnic community will only reside on the land assigned to them. In reality, ethnicity is so fluid and mixed [and the state borders are arbitrarily created for the central government to rule the people easily.]

PCMS: Yes, another strange thing is that Insein [became a warzone] right after World War II. [During the British occupation of Myanmar/Burma from 1824 to 1948], the British-Burma army has different battalions based on ethnic groups, and the Karen battalion was one of the strongest military battalions that they had. Right after [Myanmar/Burma gained] independence [from the British in 1948], the Karen battalion tried to take over lower Myanmar. There was a huge battle in Insein, and the Karen almost won. But at that time, the Chin Battalion sided with the regular Burma Army, which is one of the reasons why the Karen Army failed to take over lower Myanmar.

So, it’s kind of weird growing up as a [Chin], and they know we’re Chin. I mean, our classmates are too young to know the importance of this history, and it’s not taught in school. So, our classmates are not aware of it, and they didn’t really treat us differently. But I remember requesting a friend’s parents to study at their house one time, but they weren’t big fans of that. I didn’t know why. In retrospect, I think it’s because of that history, but it could also be something else. I don’t know.

SCHS: When did you decide to become a teacher?

PCMS: The summer between my junior and senior year [of college in 2016], I went to teach in Falam, in Chin State. Joe Decker, my former teacher at the Pre-Collegiate Program of Yangon (or PCP for short), was leading a school there. And after that summer, I knew for sure I wanted to be a teacher.

And I wanted to teach at PCP. So, right after I graduated [in 2017], I reached out. Helen Waller was the academic director then, and she was super excited to have me. But she was also leaving. So, as I became a teacher at PCP, she was no longer in Myanmar/Burma. But, I had so much fun. I was teaching sociology. Basically, based on everything I learned in college, and all the good things that I enjoyed, I get to create my own class. I did a unit on economic justice. I did a unit on identity. I took my students to a labor union office in Hlaing Thar Yar [which is the main working-class neighborhood in Yangon]. I mean, it was one of those things where I worked long hours, but it never felt like working, because I was really enjoying it.

SCHS: How did you become a public-school teacher in St. Paul, Minnesota?

PCMS: While I was teaching at PCP back in Yangon, Zara [who is now my wife] was here [in the US]; we were in a long-distance relationship and I knew that I wanted to be with her. So, in 2018, I left PCP and applied for the teaching program at the MU [University of Minnesota]. I was excited, though, because there were a lot of Karen students here. Even before starting the program, I looked up which schools had the most Karen students. I also reached out to my adviser, and they told me that the public school they worked with has students from Myanmar. So, I joined the program. It was a one-year master’s program, which was also very appealing. It’d cost less money, and I could make money right away afterwards.

But, it was intense. Academically, it was still okay, and I felt like I knew what I was doing. But as soon as I started student-teaching, it felt hard because then I was expected to do everything by myself. And for me, I was still new to the public school system in the U.S. So, it was a completely different ballgame for me. And when I started student-teaching, there wasn’t much curriculum. So, I had to create everything from scratch. But, because a lot of my students were either born here or they started in kindergarten, I couldn’t even tell if they were English language learners or not. Things got really blurred.

SCHS: Why are your students still in the English as Second Language (ESL) program then?

PCMS: They are mainly still in the ESL program because every year they have to take a test, and only if they get a certain score in the test can they exit the ESL program. But even a native English speaker will not pass it. It’s too hard. So, a lot of our students are still in [the ESL program] because the test is too hard for them.

SCHS: So, the system is kind of rigged.

PCMS: Yes, and it’s so weird. There is this vested interest in the school district to not let the students exit the program, because funding is based on the headcount of students who are labeled ESL. But also, in a way, if there is more funding, it does help everyone because we get more teachers in what we call the Language Academy [also known as the ESL programs]. But I always feel kind of icky about it, though.

Washington Technology Magnet School in St. Paul, Minnesota. Photo Courtesy of Saul Chan Htoo Sang.

SCHS: Okay. Let’s switch back to your teaching experience. So, you were telling me about your student-teaching days when you were still in the Master’s program. What was your experience like when you became a full-time teacher?

PCMS: I graduated in 2019, and I started my full-time job as an ESL teacher at the school where I’m still working. St. Paul Public Schools have what they called the Co-taught Model. Basically, there are two teachers in one classroom for English as Second Language Learners. There’s a content teacher, and then there’s an ESL teacher. Technically, we’re supposed to be co-teaching, co-planning, co-grading but a lot of the time there’s an [imbalanced] power dynamic. As an ESL teacher, I was going into [the content teachers’] classroom. Sometimes, I was considered this glorified assistant. I was paid as a teacher, but I was in the classroom just helping. I mean, my co-teachers did respect me. They allowed me to grade. They allowed me to do small group work, but on their terms. I was doing everything based on what they wanted me to do. And the curriculum already exists. So, even if I tried to come up with new things, I was only modifying the content a bit. Basically, they have the full creative control. And I have very little.

SCHS: For some context, could you talk about the school where you currently work and your students’ demographics?

PCMS: I teach at a sixth through twelfth grade school—middle and high school combined—in St. Paul. It’s one of the two schools that has a sixth through twelfth program. It’s a huge building. By building size, it’s the biggest. We have the biggest square foot in the district. And we have about 1700 students.

Half of my students are Karen (from Myanmar/Burma). And I have a couple students from Rwanda. Three Somali students. Six Latino students. And some of them I now have in my senior year class. But it’s a bit sad. A lot of my female students got pregnant, and they’ve either dropped out or they’re in a school for pregnant women and moms. But I have about five students who made it all the way to senior year. And one of them got into St. Olaf College.

SCHS: How did the immigrant communities end up in the Twin Cities?

PCMS: The Hmong came here in the late ’80s. I don’t know if you’ve heard about this. During the American-Vietnam War, a lot of Hmong served as interpreters for the American military. After the war a lot of them were targeted by the Viet Cong soldiers. Many fled to Thailand and sought asylum there. Then many of them got resettled in the US. And it was a policy back then that [the U.S. Government] wanted new immigrants to be as far away from existing immigrant communities as possible so that they would assimilate. So, they put them in places like Minnesota, where there were no former immigrant communities from Asia. So, the Hmong are the biggest Asian immigrant community in St. Paul.

The same thing happened with the Karen refugees later in the late 1990s. I have students who came here when they were in middle school.

There are also a few Ethiopian and Somali students. But more of them are in Minneapolis, so we don’t have as many of them [in St. Paul]. But even then, there’s a good ten to fifteen percent of Somali and Ethiopian students; there are also students from other African countries like Rwanda, Congo, and Kenya. But now, the more recent students in the newcomers’ program are immigrants from Latin America – El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

SCHS: Could you talk about how your Karen students and the Karen people in general got resettled in the Twin Cities?

PCMS: Many of our Karen students were refugees in Thailand. A lot of them were born in the refugee camps. Some of them had schools, some of them didn’t. So, it’s a mix. A lot of them fled to Thailand because of the civil war in Myanmar/Burma. And they call their homeland, Kaw Htoo Lei. They don’t refer to it as Karen State. Currently, there’s an active war there. [Editor’s note: The fighting is between the central government’s military, known as the Tatmadaw, and the Karen resistance armies. This conflict, which began in 1949, is considered the longest civil war in the world.]

All of them literally had to flee because there were bombs being dropped on their villages. For many of them, Thailand was home because the [refugee] camps are where they grew up. We might think camp is like this place where it’s fenced in, but it’s more like a village. There are checkpoints, but it’s not necessarily fenced in. If you want to go into a city or go through the main road, you will have to go through a checkpoint and you need paperwork. And you get support from the U.N. in terms of food, because you can’t really grow food. Some people have small farms, but it’s a different land from where they are used to [farming].

I know a lot of my students have family members who had left the camp and now are working in either Chiang Mai or Bangkok. And they decided to stay there. Also, not everyone who signed up got resettled in developed countries. I don’t know what the system is like—it might be some sort of a lottery system. But even then, some family members decided not to go because they’ve been [in the refugee camps] for like five to ten years and they have become familiar with life there. Many of them are long term residents now, although they have no official paperwork that says they’re Thai citizens or Myanmar citizens.

SCHS: It’s a problem of statelessness. I took a class called Migrants, Refugees, and Diaspora with Sharon Quinsaat, a Sociology professor at Grinnell College. We read a lot about how these camps in the borders become very dystopian-like villages. But getting back to the new immigrants coming to Minnesota, what are some of the challenges and the struggles that you see your students facing as they are making their lives in the Twin Cities?

PCMS: For most of them, they don’t know the system here well enough. I mean, they know the things that they need to know. They know how to apply for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Their parents have figured out how to file taxes. But when it comes to college planning, a lot of the students struggle with that. Also, because their parents never went to college, when you ask them things like, “Do you want to go to college?” They don’t know. They don’t know if it’s the right thing or not. Because there aren’t that many role models for them. They don’t know what options are out there after high school. They’ll just say, “I’ll work in a grocery store.” There’s nothing wrong with working in a grocery store, except for not being paid enough to have a family. And that makes me worried. Because I want them to be healthy, happy, and be able to spend quality time with their family.

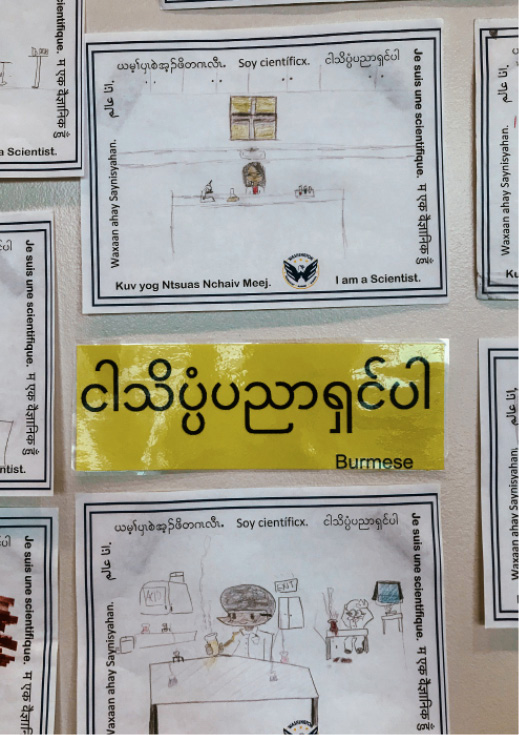

Poster Wall with Children’s Drawings with Caption: “I’m A Scientist.” Photo Courtesy of Saul Chan Htoo Sang

SCHS: What happens to your students when they don’t go to school anymore? What do they do?

PCMS: A lot of them enter service jobs like shops, restaurants, Uber. And because their parents don’t speak English, they’ll work at meat-packing factories. A few who are fortunate enough to figure out how to do college, they work for nonprofits, in the city, the government. There are some people who work for private companies, too, but not that many. The vast majority works at these odd jobs.

SCHS: As a teacher, how do you see your own teaching career going?

PCMS: Well, I’m going to quit this year. I’m taking at least a year off, because my wife and I are expecting a baby in June, I want to stay home with my baby. But part of me is also done with the teaching career. We get paid, okay, if we’re single. But as soon as you get a baby, or you want to have more than one kid, all these health insurance expenses go up. We will still be able to afford it, but we won’t be able to save any money as soon as we have one kid. And if we have two kids, it’s even going to be more costly. And my wife’s also a teacher. So, it’s not sustainable for both of us to be teaching. And I’ve always thought about doing something else. So right now, I’m thinking of just quitting and getting hopefully a stay-at-home job, or hybrid jobs so that I can be home more often. But part of me, I know, I love teaching enough that I see myself going back to the classroom; maybe five years down the road, if we only have one kid. If we have more than one, it might be a bit longer. That’s my plan for the next few years. And if this career transition works out well, the other thing I really want to do is teach at PCP again at night.

SCHS: Is there anything that you want to add?

PCMS: I feel worried about the teaching career profession in the U.S. Because I know I’m not the only one who’s quitting. A lot of people I know have quit, and [not many] newer people are not signing up to become teachers. So, I think it’s something that the U.S. must reckon with. Especially in the south, where the teachers are paid like fifteen to sixteen dollars an hour, and they make more working somewhere else. Even at our school, if you are an educational assistant, where you work with challenging kids, one-on-one, you’re getting paid like sixteen dollars an hour to be yelled at, you know. So, they’re choosing not to work in the school anymore. And they’re the ones that keep the school going, right? Because as a teacher, I have like two hundred fifty kids. But for educational assistants and teaching assistants, they work with students one-on-one, for kids who really need the support. But right now, we don’t have enough of those because they’re not being paid enough to do their job. And because of that, teachers can’t do their jobs either. Because the kids who really need the most help are not getting the help. So, they’re now just either wandering in the classroom or disrupting other kids. Or like acting out. So, it’s not good.

Peter Chan Min Sang with a group of his students at their graduation.