The following interview was inspired by a college student curious to learn how her great-grandfather’s stories from 93 years of life could help explain the past and build hope and vision for the future.

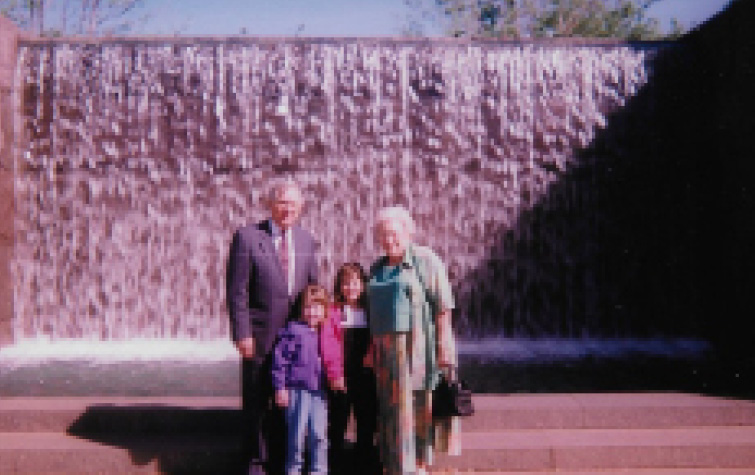

My great-grandfather, Neal Smith, was a quiet man, but there were three topics that we could always ramble on about—Grinnell College, the prairie, and agriculture.These conversations were fueled by childhood memories growing up in Iowa and our shared comfort in and love for the tall grass prairie. Our connection to Grinnell was thanks to my great-grandmother, Bea Smith. She graduated from Grinnell in 1945. My great-grandfather loved to share the story of when he arrived by train to Grinnell after returning from military service. He made it just in time to surprise my great-grandmother for her senior dance. These shared Grinnell experiences brought me closer to my great-grandparents.

While at Grinnell, I continued learning about the beauty and paradox of the tallgrass prairie: Iowa has the richest soil in the Midwest, yet its agricultural system has nearly led to its demise. While monitoring water quality in nearby creeks and spraying invasive weeds at the Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge, which supports one of the largest restored tallgrass prairies, I learned about the challenges of building a system where nature and agriculture can coexist. For instance, the existence of diverse lifeforms underpins both the natural balance and ecosystem services of nature, and while these services benefit agriculture, the principles of biodiversity are not often integrated into systems managed for production alone.

My great-grandfather also had an appreciation for these challenges and had a significant impact on conserving natural areas in Iowa during his years in Congress (1959-1995). I wanted to learn more about this, so I interviewed him while serving on the board of the Center for Prairie Studies (CPS) at Grinnell College. Along with Jon Andelson, the emeritus director of CPS, I interviewed my great-grandfather at the Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge. It was strange to see everyone excited to see and learn from my great-grandfather. Normally Neal Smith was just my great-grandfather, but during the interview I saw that he was so much more.Going into the interview, I had a hard time fathoming the amount of change he had experienced in 93 years, but it was even more shocking to hear about how many things hadn’t changed. For instance, he shared how, even after 93 years, some people still lack respect for one another and that we still struggle to live in balance with nature. But despite this, he shared that he still had hope for change, and that was inspiring to me—just a 21-year-old desperate to make a difference.

Now, ten years since the interview, I continue to see the threads of my great-grandfather’s passions sewn into my own life and work. I recently received my PhD in soil microbiology from Michigan State University and am working at the intersection of science and engagement to help build a more resilient and regenerative agricultural system that works with, instead of against, nature. Editing my great-grandfather’s words during this stage of my life helped remind me of the steady pace needed to make the changes he always believed in.

A brief recap of Neal Smith’s life

Congressman Neal Smith, Chairman of the House Small Business Committee, 1977-1980. Photo Courtesy of Tayler Ulbrich

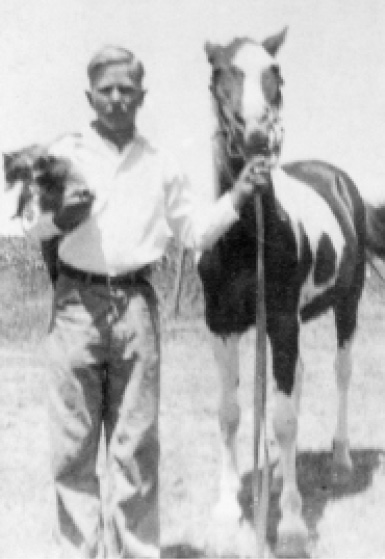

My great-grandfather, Neal Smith, was born on March 23rd, 1920, near Packwood, Iowa. He was born in a house that his great-grandfather had built. His early years spanned from the stock market crash and the Great Depression to WWII. While it is apparent that those experiences influenced his values and views on the world, my great-grandfather did not share much about the hard times. Instead, the stories I heard most often—which often made him chuckle to himself —were about the mischief he got into with his horse, Topsie, and pet raccoon.

Neal opened up more in the last years of his life, writing a book of reflections and telling my dad many stories, which my dad has since shared with me. He talked about how he helped his family during the Depression by selling pelts, collecting bounty on crows, and doing various other jobs that he could find. While he was thankful that he could help his family earn money, he never enjoyed killing anything. He had respect for animals and appreciated what they gave him, whether it was a wild animal or the domestic pigs they raised for food and income.

He also shared how, in his teenage years, President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave people hope that their lives could be better, and that the government had the ability to accomplish what individuals could or would not do alone. He talked about how cooperation is the key to change. He rarely mentioned his time in the war, only sometimes reminiscing on the funny people he met and the impact that some of his missions had on others. He also talked of the disruptive impact war has on humanity. My great-grandfather told my dad that his time in the service changed how he thought about the world, that the world became small: a finite place where all humanity exists. I think these experiences probably contributed to great-grandfather’s strong conservation ethic and belief in the need for connection and respect among people and all other species.

This belief and desire to help build connections among people may have fueled his desire to run for office. Neal served as a member of the Democratic Party for the United States House of Representatives from 1959 until 1995, which made him the longest-serving Iowan in the United States House of Representatives. He had two children, six grandchildren, and twelve great-grandchildren. He lived a long life, dying at 101 years of age on November 2, 2021.

I hope, as it did for me, this interview from my great-grandpa gives you a glimpse into the past and offers a bit of hope for the future. If someone that saw so much pain and tragedy, who also worked in the US government for 36 years, can end an interview with “It can be improved,” I think we must have hope.

TU: You have already enjoyed a long life, which means you’ve seen a lot of changes in your lifetime—in the world, in the United States, and in Iowa. Of the changes you’ve seen in your home state, which ones stand out as the most significant changes?

NS: Well, I was raised during the Depression on a farm near Packwood, Iowa. Anybody who was raised during the Depression saw significant changes. The railroad was about a mile away from our house. And our place was on a steep grade, so the trains slowed down when they came close to us. People who didn’t have a job and were riding the rails would jump off the train, come to our place, and ask for something to eat. The government began getting involved in programs to simply help lots of people survive. The other change that really impresses me, when I think back, is how much technology has changed life, especially in communication. In those days we got a weekly paper from Kansas City. And you didn’t have television and radio and all these things that have come along since then. All these things changed a lot.

TU: Iowa has also seen a lot of changes in its landscape. It has long been known as the agricultural state, and I’m especially interested in how you view the extensive changes that you’ve witnessed in agriculture and the farming way of life in the course of your lifetime. Do you see these changes as positive or negative?

NS: Well, of course, the big change is in the amount of food—corn, beef, and so on—one person can produce. It is just a huge, huge change. So, for instance, when I was in my late teens, if a farmer had more than 40 acres of corn, they couldn’t husk it all themselves. They had to hire somebody to help them. Today, with machinery, a farmer can harvest hundreds of acres of corn, even thousands. Yields are way up, too. So, technology’s been a big difference.

Neal Smith at fourteen with his horse and pet raccoon at the family farm in Packwood, Iowa, in 1934. Photo Courtesy of Tayler Ulbrich

TU: The natural environment is suffering in many parts of the country and the world, and, in many cases, this is impacted by agriculture. Is it possible for natural areas like the [Neal Smith National Wildlife] Refuge and agriculture to coexist?

NS: Well, what I think many people don’t appreciate enough is that different kinds of soil should be treated differently. For instance, some of the flat land north of Des Moines is heavy and solid and gummy. Near where I was raised, the soil was real black on top. But you get down about three feet and it’s blue. But you dig that blue out and put it up on top and in a year or two, it’s black. It was the same soil, but it didn’t have oxygen. And so, in the same field you could have two different kinds [of soil]. Now here where we are at the Refuge, the soil drains deeply, fairly easily. Some places down south of here they have almost a hard pan just a foot down under the ground. So, these soils must be handled differently. Another example is that there’s a place on this Refuge where they found that six feet of soil had been eroded away. It was very rich soil, but also highly erodible. But if you go south of here, if you get down two feet, there’s no richness at all.

TU: So maybe just being more aware of the soil types would allow us to manage the land cover in a way that would be more efficient?

NS: I hear people say everybody ought to do a certain kind of farming. Well, you have different weather, different soil. So, there isn’t just one type of farming [that’s] appropriate, no one rule fits all.

TU: Many people would say that one of the most important developments in recent history has been the rise of the environmental movement generally. Why do you think the environmental movement began and what triggered that change?

NS: We’ve always had some people that are sort of up-in-arms and others that are not. In some cases, people who lived in the city and have never been exposed to other species, or hardly at all, don’t think much about the environment. Their environment is concrete and high buildings. For other people, who are closer to the environment, it’s different. Here at the Refuge, they had 7,600 schoolchildren visit last year [2013], and some years they’ve had more. Even more would like to come, but it’s hard to handle them all. In Iowa, the land was plowed up and we didn’t have forests and mountains and things, so we don’t have as much nature for them to visit. That is very important.

Congressman Neal Smith with then-Senator John F. Kennedy, 1959. Photo courtesy of tayler ulbrich

There’s always been some people more concerned about the environment than others, but there are some that have never been exposed to nature in a way that would make them want to know more about it. With regard to your question about why so many more people are involved… I’m not sure there are more people—a greater percentage—involved. But another interesting thing is how technology has changed the experience of nature. It used to be you went to the Rocky Mountains maybe once in your lifetime. Now you can watch TV and see more of the Rocky Mountains than you used to if you went out there.

TU: That’s so true. You’re known for having very strong environmental values. What experiences in your life shaped these?

NS: Growing up during the Great Depression shaped them. There had to be a certain amount of saving anything, people had to do whatever they could to get to next week. If you didn’t have coal, you burned corn for warmth. Also, one of the things we have here at the Refuge is the opportunity to see what has happened on this piece of land over 170 years. You need to learn from that.

TU: Did your conservation values influence your approach to public policy when you were in office?

NS: Well, they did. Any experience that anybody has influences their interest in some subjects more than other subjects. If you haven’t had certain experiences, you won’t be that interested or won’t know how to value certain subjects. So, experiences do make a difference. For anybody that’s working with public policy, background makes a difference.

TU: There has been a long-term research project at the Refuge called the STRIPS project [Science-Based Trials of Row-Crops Integrated with Prairie Strips], which is where they’re studying how integrating small strips of prairie within row crop agriculture might benefit the landscape and ecosystem surrounding it. Have you heard about this study, and what do you think of it?

NS: Well, any of those kinds of studies are good. Yeah, you recognize that to do it in one field may not be what you do in another. For example, when I was farming, I had some land that needed a way to control the runoff. So, I used strips too! I used switchgrass, pure switchgrass. And some of the conservation people think you shouldn’t use switchgrass and they have some other combinations that they want people to use. But I used switchgrass, even though I did not get any government help with planting it, because I wanted it that badly. And then three years later, after it got established very well, some of the conservation people were bringing people to see it. But people are still learning. Yeah, still learning.

TU: How can we address these topics when we’re talking to farmers or conservation districts about implementing conservation measures?

NS: When you talk to someone, what they know is on their own farm, in their conditions. It’s really difficult for some of them to understand that you can’t use the same methods everywhere and expect to have the same effect. And they have to recognize that different parcels of their land are different. We’ve got farms between here and Des Moines where part of the soil on the farm is from that last glacier and the other half of it was made 8000 years before that. The farmers have fields that need to be treated differently.

TU: Some people argue that conservation practices should be made mandatory rather than voluntary. What is your opinion about that? Also, how could we provide money for farmers to install such practices if we did, in fact, make them mandatory?

NS: Well, we do have programs that offer cost-share for conservation measures. However, there’s no one smart enough to write a bill for the right kind of program for each and every farmer, and each and every kind of soil. Some of the results have got to come from experience. It’s just different. You just can’t write a mandatory procedure for all conditions. So, you can have minimum things [limits], but to say that all farmers must do X or Y is never going to work.

TU: What do you think would be the way around that?

NS: The way we have been doing it: we agree and still debate. Somebody tries to make something more mandatory, then they find out that causes a condition that they didn’t expect to see, and they try to change it some more.There are always people working [on it].

Neal Smith with U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Director Mollie Beattie and other dignitaries, planting native species during Prairie Learning Center Ground Breaking, September 1st, 1994. Photo courtesy of Fish & Wildlife Service and Neal Smith NWR

TU: Recently, there has been a large push for social and environmental changes to happen through small localized grassroot organizations and movements that can then hopefully spread into more general belief-systems and policies. What do you think about the power and sustainability of those small grassroots movements. Do you think that’s the best way for people to influence governmental policies, or if not that, what’s the best way a person can help influence?

NS: Well, the main thing I think about is…we’ve always had some of that. It increased greatly during the Johnson administration. Johnson had some programs that affected cities, especially. During his administration [1963-1969], they encouraged growth of organizations that would speak up and have ever since. But the main thing these organizations need to remember is to be respectful of others and not to force their beliefs, you know. Some of them get out of hand; they only see their own situation. The main thing is: be respectful of others, express yourself, and let them know what your situation is and why you think something. So, to that extent, these organizations are good.

TU: Do you think that the small grassroots organizations have power?

NS: Yes, there is some. But their power and their influence are much greater if they are respectful and try to understand that others may have a different situation.

Future generations and Iowa agriculture

TU: I’m wondering what you think Iowa agriculture will look like in another generation? Will there be anything left of the yeoman farmer ideal that Thomas Jefferson believed was such an important foundation of democracy?

NS: There will always be some. As a matter of fact, there may be more of them right now than there were 10 years ago. There will always be some with different ideas and investment possibilities, and different abilities to respond.

TU: Many people think that education will play a vital role in shaping the future. The Walnut Creek National Wildlife Refuge, which is now renamed in your honor, is trying to educate the people of Iowa—like the students you said that visit and other visitors—about the prairie. What do you see as the ultimate purpose of this education?

NS: Well, it’s so that, in the end, we live in a place we understand and know.

TU: My father told me that you taught him how to make willow whistles on the streets of DC when he was a kid, and that this helped him realize that nature can exist in a city. I think that’s missing for a lot of children that are now growing up in urban areas. How do you think that educators and policymakers should work on improving environmental education in urban areas?

NS: We need to expose people as soon as we can to other species. I have seen it here so many times. Ten miles from here, there are people and young children or teenagers that hardly know that there are other species in the world besides them. They come here to the Refuge, and I see it. I saw a little boy get so excited when he looked up at the exhibit with the cross-section of grass roots under the ground. He said, “I didn’t know grass grows below the ground.” He thought grass only grows up.

TU: Did you have close contact with nature growing up?

NS: I spent hours and hours and hours in the timber. I lived on a farm, and there was a pasture and creek running through it. And there were trees along the creek, with a couple more timbers a mile away. So, I spent a lot of time just out sitting and watching and observing, listening to the species talk to one another. I mean, they don’t talk to one another, but each species in the timber knows what others are saying. For example, when an enemy of some kind comes through the timber, say a coyote or something, a bird will fly through cackckckaka [sound effect]. The squirrels know what the bird says, and they run up the tree. But they couldn’t answer back. They communicate by listening. So, yes, I spent a lot of time in timber watching. And I remember so well that when I was very, very small, probably four or five years old, I discovered that no matter what two trees you looked at they were in line with one another. I thought I really had discovered something. [laughter]. And I saw that it wasn’t true with three trees! Just observation, you learn a lot with observation.

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2023-spring/ulbrich-6-volume-ix-issue-1-spring-2023.jpg)

Monarch butterfly on a prairie sunflower. Photo courtesy of Joan Van Gorp, President and Community Coordinator for Friends of the Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge

TU: Do you think that your connection with nature has helped you in your relationships with people because you learned how to observe and how to see things work together?

NS: I think that knowing [and] appreciating other species is always helpful. There are so many thousands of species in the world. You observe them, how they get along, and how they protect themselves while they’re devouring others.

Bison herd at the Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge (NWR). Photo courtesy of Joan Van Gorp, President and Community Coordinator for Friends of the Neal Smith NWR

Jon Andelson: I’d like to follow up if I may with one question about that. I’m a little worried that — maybe especially in Iowa—it’s getting harder and harder for those other species to live. You remember Earl Butz telling farmers to plant fence row to fence row. Most farmers are doing that. There’s very little wild land on a farm anymore. Do you have any thoughts about that? Are we making it hard for other species to live?

NS: Yes, we are. But it’s important to do what we’re doing here at the Refuge — trying to re-establish species so that you see them, and you can know how they operated in the past. It’s very difficult to re-establish some species. It was too bad that the tall grass prairie was such good farmland. It would have been so much better if maybe 50,000 acres had been reserved somewhere. But we have less than 1% of the original tallgrass prairie left, and that’s not enough. You can’t have buffalo very many places. But right here at the Refuge they’ve found species that people didn’t even know were here; [the species] have come back on their own after 75 years, once the right conditions appeared.

JA: Maybe you remember the name Ada Hayden. She was an early naturalist in Iowa. Hayden Prairie is named for her. She published an essay in 1916 that Tayler actually read at one of our events [for the Center for Prairie Studies]. Way back in 1916, Hayden called for the preservation of just one quarter-section of original prairie in every township in Iowa for the ecological knowledge it could give us. It’s a pity that we didn’t follow her advice.

NS: They just didn’t think about how valuable it would be for future generations 100 years ago. “Well, I want to plow that up because I need it right now.” Yeah. When I was in Congress, we set aside a lot of land in the West that was about to be torn up.

JA: I think they’re trying to take away some of that protection.

NS: Yes, they are.

JA: One of the concerns that I’ve had about agriculture in Iowa is all the chemicals being used, because some of the chemicals are intended to kill things, the insecticides and so on. And I’m especially concerned about it from the standpoint of the soil, because what makes Iowa soil so special is the life in it. It’s got all the microorganisms; it’s got all the root structures and so on. What you see in the exhibits here at the Refuge shows that very clearly, but we’ve become so reliant on insecticides that we’re killing the life in the soil. Do you think there is a solution to that?

NS: Well, we’re overpopulated, and we’re responding to that to try and get more and more food from the land. So, we have special corn varieties that have been developed now, it’s mostly feedstock and food stock. So that means you use more and more and more chemicals.

JA: Do you think there’s any way that we can return to a more diversified farming like we had in the past?

NS: Well, we have some diversified farming, but it’d be very difficult for many people to farm that way.

Reflections on Neal Smith’s political career

JA: I wanted to ask a question about the United States as a whole, which has been through a lot of very challenging political periods in its life. You mentioned the Great Depression, which certainly is one of them. World War II, obviously, the whole Vietnam era and the political turmoil that it created, the more recent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the collapse of the markets in 2008. Are there some political periods that you think that we as a country handled better than others?

NS: Oh, no question about that. The World Wars, for example, especially World War II. During World War II, overnight it went from two-thirds of the people being against it, to everyone being for it, to everybody united.

JA: December 7.

NS: Yes, it made a difference because we were attacked.

JA: Do you have any thoughts on the Kennedy administration [1961-1963] since you were in Congress at that time?

NS: Kennedy had a lot of good ideas, but they didn’t get implemented. Then Johnson picked them up and passed them. In other words, they were creative people who were thinking of something, but accomplishing it was something else. And some of that was not their fault. Johnson had a unique background. He was from the South, but not from the Deep South. And he had the ability to get along with everybody, no matter where they were from. And even more important, he had the ability to know how to put coalitions together. And he had the ability to realize what had to be done to get the right kind of coalition to do one thing, even though they were opposed to something else. He was unique in his ability. The conditions today are different. Years ago, we had the Southern Democrats and Northern Democrats and Republicans. You really had three parties, and you had to put different coalitions together. In the last election, the majority of the people voted for a Democratic House of Representatives, but because of how districts are set up we have a Republican House. So, you don’t have the voice of the people. To have that we may need to have some kind of constitutional amendment, which would be very difficult to pass. Former [Supreme Court] Justice Stevens has proposed one. He says we need to think about changing the constitution once in a while to match the changes in the times. During my service of 36 years, we had five amendments to the Constitution. In the last 20 years we’ve had virtually none.

JA: I’m under the impression that a lot of the problems come from the re-districting procedures.

NS: That’s one of the things that [Justice] Stephens is talking about. Through redistricting you end up with some districts that are 80 percent one party or the other, and not enough are between 45 and 55. There are other things that would be almost impossible to change. One is that the small states are not wanting to give up having two senators. So now there are 21 states, with 42 senators, that have the same population as California with two. You don’t have majority rule when you have that.

JA: Well, the Constitution was also set up to protect the rights of the minority and the small states.

NS: Well, it was set up as if each state was an independent country.

Lessons from the past

Neal Smith and wife Bea with Great-Granddaughters Madison (center left) and Tayler (center right) in 1996 at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial in Washington, DC. Photo courtesy of tayler ulbirch

JA: A few minutes ago, I referred to the various crises of the 20th century. I’m curious to know your thoughts about what lessons the American people should draw from the crises of the 20th century.

NS: We draw lessons from each one of them. Not immediately, maybe 50 years later. From World War II, how up until December 7th, the overwhelming majority said, “Well, there’s a big ocean between us and those people are over there, and that acts to protect us. We don’t want to have anything to do with them.” So, we ignored what Hitler was doing. And then all at once you find out it does affect you. Lessons can be learned from each one of these crises, but in many cases almost nobody foresees the lesson.

JA: What was the lesson of the Great Depression?

NS: The Great Depression showed Americans that things get done by getting together and utilizing the government as a tool. We did something that benefited almost all the people. It wouldn’t have happened unless they did it through government.

JA: I’m feeling a little pessimistic right now about the government. There seems to be a kind of inability to work across the aisle. Do you see some hope?

NS: Well, it’s difficult. It started in the early 1990s, it started with the majority of each party making the minority go along with [their preferences]. And I never thought I would ever, ever see anything like the Hastert Rule. [Editor’s Note: “The Hastert Rule says that the Speaker will not schedule a floor vote on any bill that does not have majority support within their party – even if the majority of the members of the House would vote to pass it” - Wikipedia.]

JA: So where does the hope lie?

NS: It is going to be very, very difficult to make some changes that would improve things, but there are some that can be made. There’s hope. You’ve got to think things can be done. A lot of things can be done to improve it, even if it isn’t going to change fundamentally. It can be improved.

JA: Well, it’s probably never been 100 percent.

NS: No, no it never has.

Elk grazing at the Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge (NWR). Photo by the U.S. Geological Survey