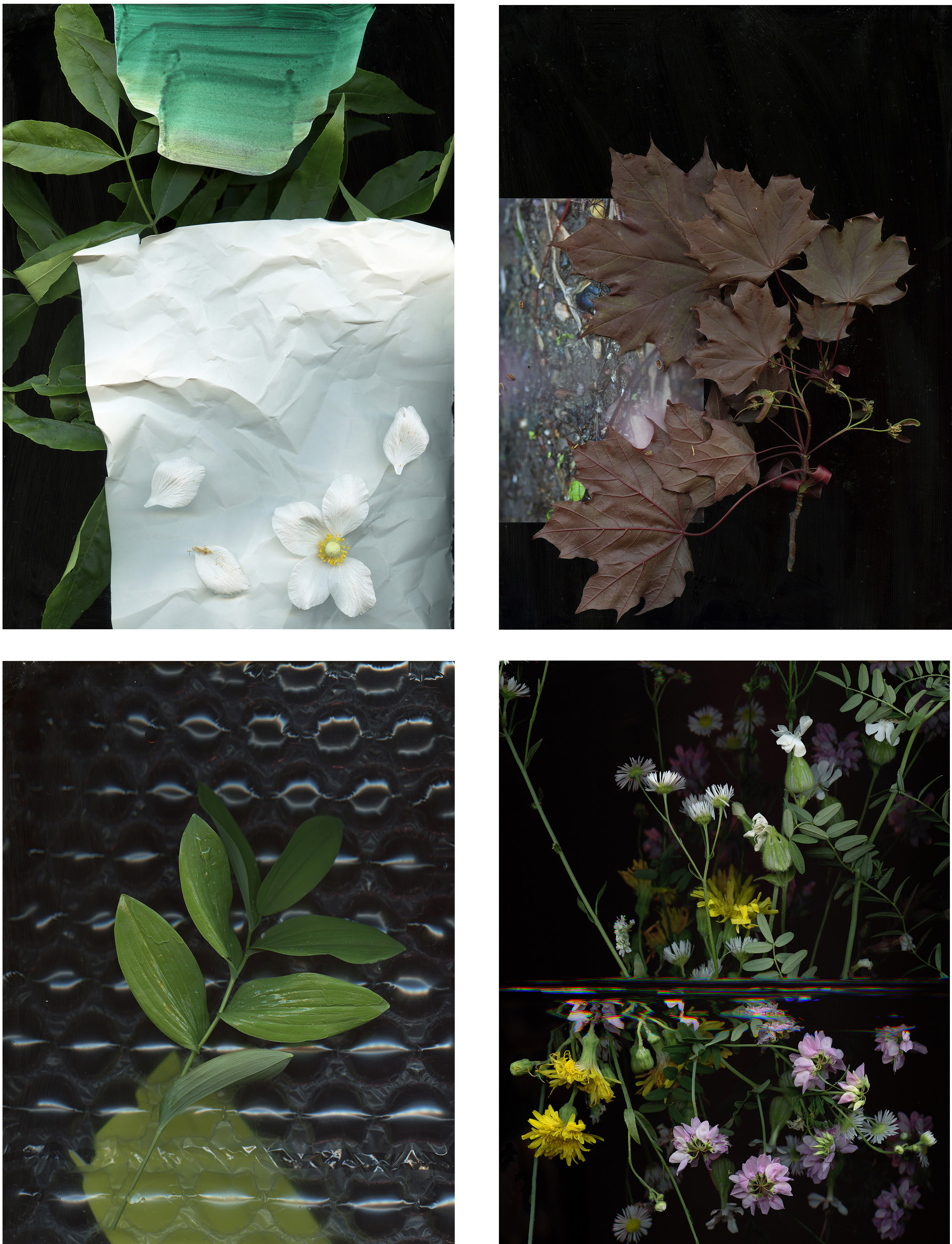

“Prairie Constructs #35 & #36,” Archival Inkjet Print, each image 36 x 54 inches, by Regan Golden, 2015

For the past decade my artwork and research has focused on ’edgelands,' from a forest in Massachusetts bordering a subdivision to a ragged prairie in Minnesota running along a railyard. Edgelands act like scrims rendering other spaces invisible, yet the edgelands are absent from most city maps. This wavering visibility seeps into my photographs and drawings: the soft villous hairs on the unfurling fern fronds are partially obscured by a puddle of green paint. Edgelands are considered one of the last refuges of wildness. I photograph and draw the plants I discover in these overgrown patches of “weeds” as the seasons change. My images are as much about making visible this overlooked landscape as they are about documenting the passage of time.

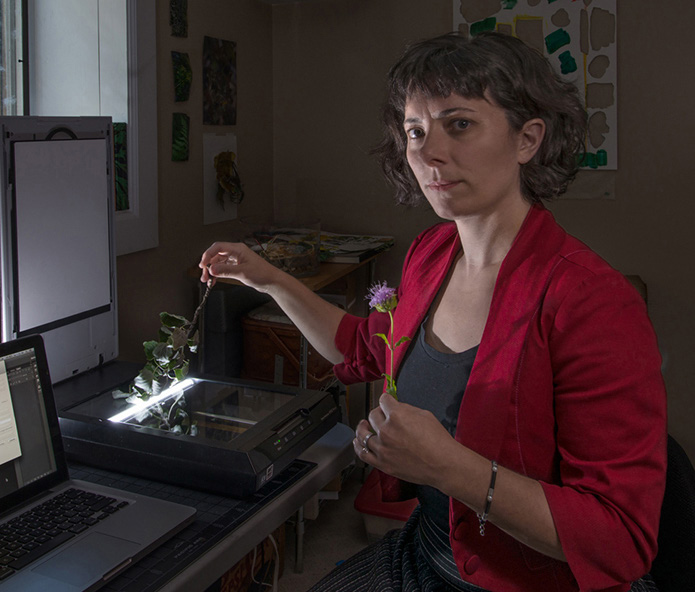

“The Prairie Constructs” are an ongoing series which catalogs the life and death of plants from the edgelands of Minneapolis. Made almost entirely on the scanner bed, The Prairie Constructs are a digital version of a photogram or botanical solar print. The images are shown as both large-scale digital color prints and as an artist book or compendium, showing the evolution in the landscape over the course of a year. What started as a way of collecting bits and pieces of plants as the seasons change has turned into a methodical and sometimes frenetic project of gathering and experimenting with each plant.

Since I often uncover synthetic materials, plastic bags mostly, as I collect plants I included these in the images as well.

Chance also plays an important role because the view from below of the scanner is not visible until the image appears on my screen. I place my materials within the frame and then document them as they react and evolve (melt, flow, crumple, wilt), often making multiple scans from a single combination of paint, photographs, plants and plastics. I orchestrate this “organic process” that is then recorded and amplified through digital technology.

Light is an important ingredient in the transformation of my materials

and in the elevation of these spaces. I work with light when

photographing the landscape, making the scans and installing the images.

In traditional landscape painting, light can be interpreted as lumen,

observed light, or lux, divine light or the light of reason. I prefer

to think about light in terms of Heidegger’s description of lichtung,

which translates as “light in a forest clearing.” He argues that

openness must precede lumen and lux, observation and judgment. My

work enables me to be open to the natural world that is around me, even

in the city. It is this sense of wonder and awareness about the

persistence of urban nature that I want to pass on to viewers through my

images.

“Prairie Construct #41,” Archival Inkjet Print, 36 x 54 inches, by Regan Golden, 2015

Clockwise from top left, “Prairie Construct #23, #5, #37 & #18,” Archival Inkjet Print, each image 36 x 54 inches, by Regan Golden, 2015