Born in the Midwest at nearly the exact middle of the 20th Century, Dartanyan Brown has been front-and-center for many of American culture’s most defining struggles, particularly the Civil Rights movement and the advent of revolutions in music and technology. Where many people content themselves with one career, Brown has had at least four: in journalism, in musical performance, in the tech sector and in education. Through it all, he has continued to forge ahead with an optimism and openness to connection that he learned in a family guided by a strong maternal grandmother who grew up in an integrated Iowa town where she “didn’t know nothin’ ‘bout no segregation!”

This unique foundation, along with the exceptional outlook this gave him, has enabled him to live what he refers to as “My Integrated Life.”

In this issue of Rootstalk*, we’re running Part I of his remarkable story. Part II will appear in the Spring 2019 issue.*

My name is Dartanyan Brown. I’m an African-American conceived in California and born in 1949 in Des Moines, Iowa.

I’m also a former Des Moines Register 1 reporter, as well as a third-generation musician with deep roots in American Jazz, Folk, Rock ’n Roll and Electronic music traditions. I’ve also been an educational technology enthusiast, though I label myself an artist-educator, having spent over 40 years creating interdisciplinary arts-centered curricula for students in public- and college-preparatory environments.

That I identify as all these things and more is a testimony to the family, community and educational influences that aligned through the years on my behalf. Reflecting on over six decades of experience, I can say that having been born in Iowa prepared me well for a fantastic journey that I like to describe as My Integrated Life.

Buxton Roots

To begin, let’s travel back in time 122 years ago to a coal seam in Monroe County, Iowa, owned by the Consolidation Coal Co. of Chicago. The town that grew up around the mine, Buxton 2 (near present day Albia), was named eponymously for its manager, Ben C. Buxton. That was where my great-grandparents, Ross and Blanche Johnson, arrived from Virginia in 1895. Why did they travel so far?

To understand why my grandparents and other African Americans perceived Iowa as a place of refuge, we have to understand the conditions they endured in 1890’s Virginia. In the year 1894, African Americans were actually the majority of the population of Albemarle County, Virginia. (The county was home to 606 free Blacks and 13,916 enslaved African Americans, compared to 12,103 Whites.) Of course, fear of that Black majority engendered the kinds of naked oppression you might expect from those dedicated to maintaining White supremacy by any means necessary. Segregation was the rule in every area of Charlottesville public life.

Ross Johnson, my great-grandfather was well aware of social, vocational and economic lines that could or could not be crossed. Even a casual review of what my ancestors endured in Jim Crow Virginia serves to underline the hope and possibility that buoyed them on their journey out of the South. During the Civil War, Iowa had been on the Union side of things (thank goodness!) and so this land was blessed with a somewhat more progressive, humanistic perspective than, say, Missouri or the states that had been in the Confederacy. So, Ross and Blanch Porter Johnson left Charlottesville in 1893 for coal mining work on the Iowa prairie. My grandmother, Lettie Porter Thompson, was born in Monroe County on November 19, 1896.

As a child in Iowa, Lettie experienced a totally different social matrix than the one she would’ve endured in Charlottesville. That is not to say her family members didn’t experience reduced opportunities because of their skin color, but life was materially better in Iowa if for no other reason than that they were able to take advantage of social and educational opportunities denied them in the South.

That my Grandmother could proudly say of her Iowa childhood: “we didn’t know nothin’ ‘bout no segregation!” meant that something very significant had occurred. With a gleam in her eye that was still there in her 80s, she told me, “The happiest time was getting out for recess because you could play with ALL the children on the playground.”

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2018-fall/grinnell_28318_OBJ.jpg)

Buxton, Iowa, as it was at the turn of the 19th and 20th Centuries. Public-domain image from Blackpast.org.

Over the years, my grandmother described Buxton as generally a very good place to grow up. “I don’t like this one, I don’t like that one…can’t go here, can’t go there…we never had that nonsense!” That was Lettie…always keeping it real. Perhaps the most important thing was that you could get along with people, and basic respect was accorded to just about everyone—unless you couldn’t handle your liquor.

Her biggest regret was leaving high school before graduation. Working to help support the family was necessary, though, and so while her two sisters, Katherine and Anzul, were able to finish high school (Katherine was a state debate champion in the late 30s), Lettie, also a fine musician, sacrificed her potential opportunities for the sake of others in the family.

The grace with which Lettie Thompson lived her life was a model for folks both Black and White. As I mentioned, she wouldn’t allow talk about racial disharmony, and she instilled high standards in her family in terms of education, personal behavior and vocational excellence. .

Getting along with people of any ethnicity was the hallmark of my grandmother’s philosophy of life. She lived it and wouldn’t tolerate any derogatory talk about anyone. When I was a youngster, my parents would go for drives, visiting friends both Black and White in little communities outside of Des Moines. Mom and Dad would pack my two brothers (Kevan and Don) and me into dad’s beloved ‘55 Dodge and head off to Albia, Marshalltown, Perry or somewhere else where the family had friends from the Buxton days.

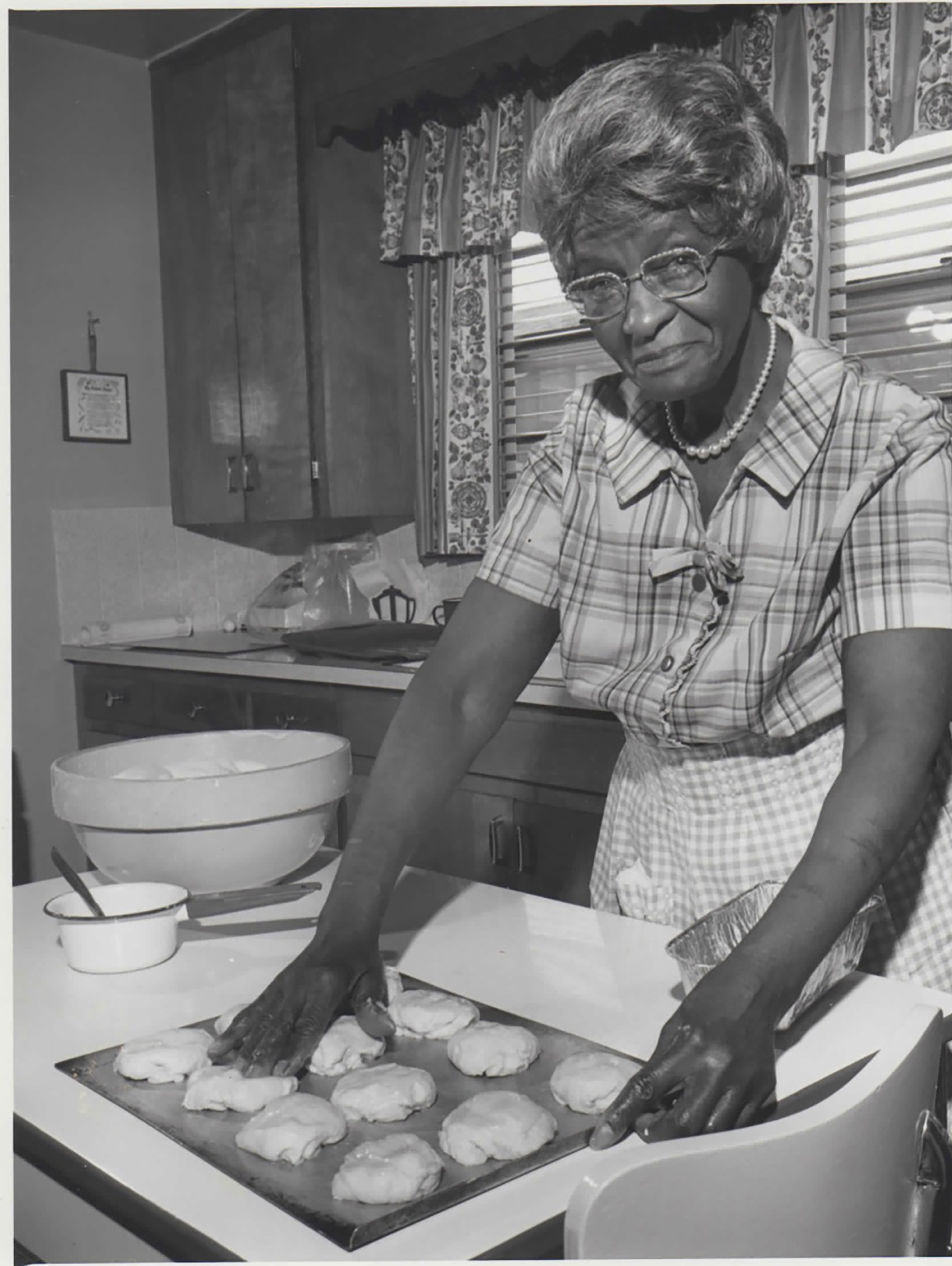

Dartanyan’s grandmother, Lettie Porter Thompson

I remember hearing about The Buxton Club 3, a social circle of mainly women whose families had roots in Buxton/Monroe County. In the summer of 2018, I was happy to find out that the Buxton Club still sustains the memory of the place. It’s amazing that over a century later, the memories of Buxton still have a powerful impact on those whose predecessors directly experienced it. Without question, these are the cornerstones of My Integrated Life.

My maternal family’s experience in Buxton was key to establishing sympathetic, forthright relationships with people regardless of ethnic or racial difference. My parents’ expansive worldview and pursuit of knowledge across disciplines was pivotal in shaping my view of music, education, technology and culture. It is the matrix from which springs the experiences I write about here.

My Parents Meet

My father, Philadelphia-born Ellsworth T. Brown, met my mother, Mary Alice Thompson, in Los Angeles after the Second World War. Mom was studying music at Los Angeles City College and working as an extruder at Lockheed Aircraft when dad returned stateside after his wartime duties in the Merchant Marine. They got married in early 1949. A few months before I was due to be born, Mom decided that she wanted to be near her family. Ellsworth and Mary left L.A. and moved back to Iowa—just in time for me to arrive in October of 1949 at Mercy Hospital.

We lived at 1434 Walker Street on Des Moines’ east side. It was integrated like Buxton was, and we had lots of Jewish, African-American, Latino and European-American neighbors.

In the mid-50s the Walker Street house was a hub for rehearsals, jam sessions, and music lessons for students like 16-year-old Frank Perowsky 4 who left Des Moines to forge an incredible career as an arranger, instrumentalist, studio musician and recording artist in New York City. Dad even had a system you could use to press your own recordings 5 from blank vinyl discs. (Don’t ask me how that worked!!)

Ernest “Speck” Redd 6—originally from Hannibal, Missouri—while certainly not the only good piano player, was the most respected African American jazz piano player of the 50s and 60s in Des Moines. Because he lived three blocks down Walker Street from us, there were frequent music sessions involving him and my father. Charlie Parker 7 was the reigning king of Jazz at that time, and I remember spirited discussions between the musicians about how to interpret Bird’s musical innovations. Speck was posthumously inducted into the Des Moines Community Jazz Center (CJC) Jazz Hall of Fame 8 in 2005. My dad’s induction came in 2010.

Dad was a bebopper (bebop 9 being a kind of jazz introduced during the 1940s by innovators like Charlie Parker); Mom loved Rhumba, Merengue, and European Classical music of all kinds. I was immersed in these sounds, almost inundated with them, from the time I was born. I would sing (Mom would call it yowling) along with records—no matter what style.

Though my parents later divorced and for a time my father drifted out of my life, this was a time when I gained my basic appreciation for ALL music dedicated to telling stories and bringing healing to our beleaguered souls.

My early exposure to technology

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines the word integration as “incorporating or coordinating separate elements as equals into a social environment.” It also has a significant, though different, meaning in the world of mathematics.

My father was familiar with both the social and the mathematical contexts for integration. Ellsworth had been one of the few Black radio officers in the Merchant Marine during WWII. Dad integrated his aptitude for mathematics into his love of music, and this led him to the Schillinger System of Musical Composition 10. Years later, at my father’s induction into the Iowa Jazz Hall of Fame, I learned from his friends in attendance that he brought musicians to our Walker Street house to teach them the Schillinger System.

Dartanyan’s musical parents, Ellsworth and Mary Alice

Music, mathematics and technology were completely integrated in my father’s mind. In my 20s, when I encountered the writings of R. Buckminster Fuller 11, I found someone who could clearly articulate complicated ideas in the same way my father could. Bucky’s Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth 12 was an inspiration, and it remains an inspiration to this day.

Dad also collected radios, and the pieces in his collection were objects of fascination for me. I remember a small room in our house that was filled with scopes and electronic parts. As a youngster watching television (we baby boomers were the first TV generation) I was awed by science fiction serials of the day (Captain Video 13 anyone?). The radios on Dad’s worktable had these things called “tubes” inside, and to me they looked like little spaceships. I delighted in removing them from the back of old radios and zooming them around the room flying my mission to Mars.

The 60s: Music, and The Register

According to my grandmother and everyone else I knew, if there was something I wanted to do, I had to get out there, prepare myself and go for it. During the tumultuous years of the 1960s, I would find myself pursuing ambitions in two realms: the literary and the musical.

As a child in 1954-56, I had watched Superman on television, but rather than Superman, I wanted to be Clark Kent, the mild-mannered reporter. At age 12, I decided I wanted to be a writer.

In a similar way, my childhood experience growing up in a hub of the musical community primed me also for a passionate, lifelong obsession with music. It seems fitting that a decade so filled with foment and change for our country should also be transformational for me personally. It is yet another example of integration as my life’s theme.

In 1964, my best friend George T. Clinton (whom we called “G.T.”) played the Hammond B3 organ in a band called The Upsetters. It included drummer Jimmy Brown, guitarist Bernie Fogel and bassist Wally Ackerson. I blame these guys for destroying what was left of my resistance to making music a participation sport. George lived in what was called the “Southeast Bottoms” or Chesterfield district of Des Moines. Raised in the Shiloh Baptist Church, G.T. was steeped in Gospel and Praise music, but he also studied jazz extensively with our neighbor Speck Redd while he was still in middle school. By 1964, he had added the “gospel” of Little Richard to his repertoire, and became Des Moines’ first Beatles-era “rock star”. His musical talent was matched by a dangerously sexy rock star attitude that Jagger himself might have envied. An African-American with a Beatle haircut (!) and an instinct for knowing where the music of our generation was heading, George introduced me to memorable jazz and rock music experiences long before I considered actually performing myself.

He introduced me to a local Jazz Festival at the First Unitarian Church and took me to the KRNT Theater to see Illinois Speed Press 14 and Chicago Transit Authority (later Chicago 15), as well as Veterans Auditorium to hear Cream 16 (god, Eric Clapton played LOUD!!). He started taking me to his bands’ rehearsals and asked the bassist to show me how to play a blues bass line.

After a lot of practicing in the basement, I was playing bass myself, and in the winter of 1968 I went with a group of friends to the Drake Fieldhouse for a concert by a band from Chicago.

It was the Paul Butterfield Blues Band 17 featuring the legendary harmonica player and singer. He introduced 17-year-old Buzz Feiten on guitar to us. Also on board were Phillip Wilson on drums, Tenor saxophone player/vocalist and songwriter Brother Gene Dinwiddie, and I think David Sanborn was in there, too, on alto saxophone.

I had never heard of this band before, but after the concert I went out and bought their new album (“The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw 18”) and lost the rest of my mind while playing it.

Everything about this music confirmed that something big was missing from my own life. My mother and father had divorced sometime in the 1961 through 1963 period. I’m not sure when, exactly, because between the ages of 11-13, memories of my father seemed to just gradually fade away. My brothers and I were used to him going to out of town engagements, but as I got into middle school I realized that he was just…gone. I must’ve eventually been told the who/what/why/when and how of the situation but that didn’t soften the emotional upset.

The songs, the lyrics, the sound…everything about the music I began listening to after the Paul Butterfield concert seemed to beckon me back home. There was something so inherently comforting and challenging at the same time that something inside of me literally cracked open, I suppose. What was revealed was a yawning cavern of stuffed pain, questioning and longing to understand what, besides my dad, happened to be missing from my life.

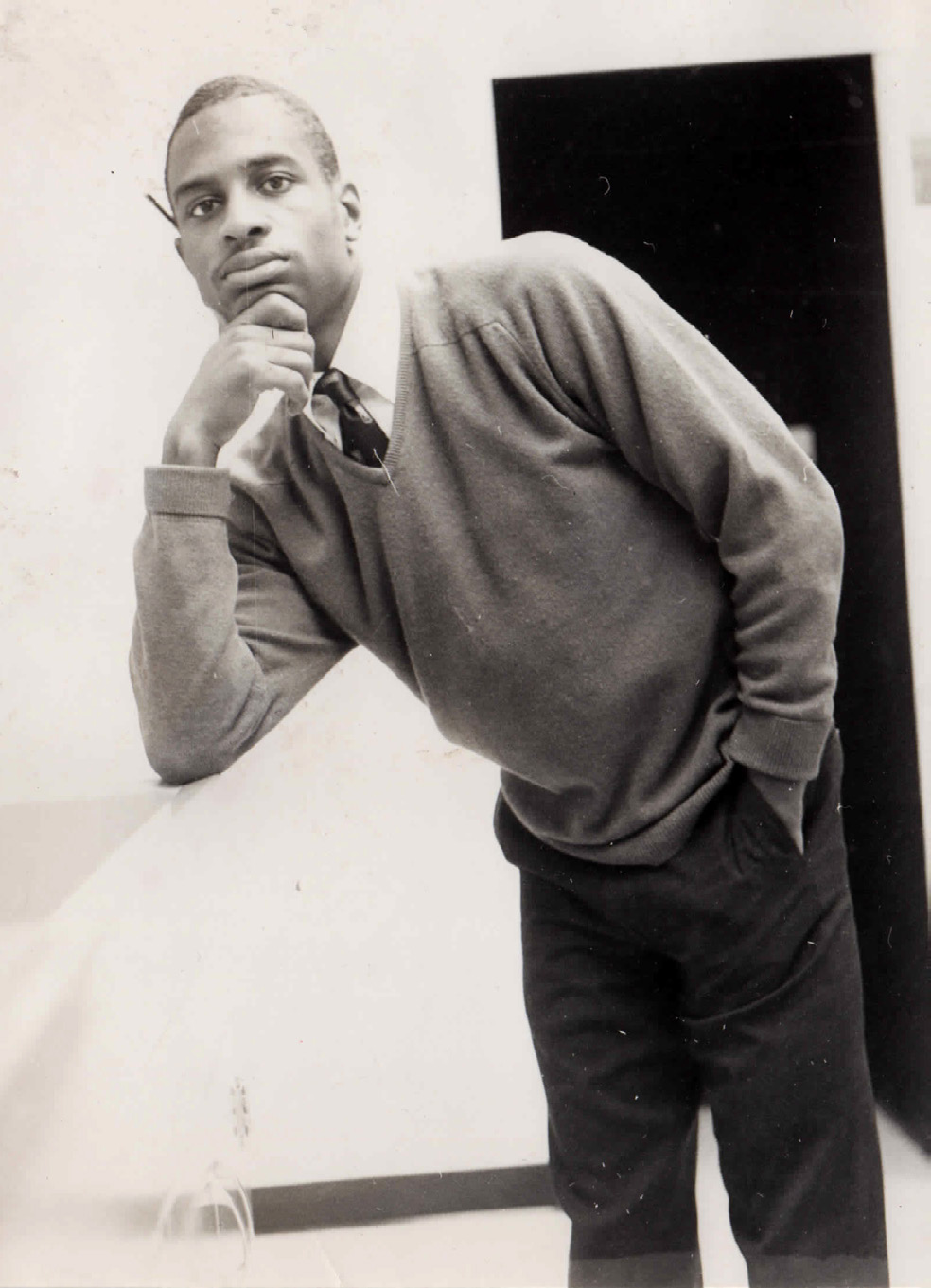

A portrait of the artist as a young journalist. Dartanyan at the offices of the Drake Times Delphic

I struggled to deal with feelings that had nothing to do with striving, with achieving, or with caring about social position. I discovered the primal longing that each of us is subject to as human beings. It was the simple realization that my family had fractured and I had tried to act as if nothing was wrong in the years since the divorce. My brothers and I were trained to keep moving forward and not to talk, think about, or acknowledge the chaos that enveloped our lives in the years 1960-70.

After the Butterfield Concert, with friends Rick Arbuckle, Paul Micich, Frank Tribble, and Sylvester Strother, I started the Black and Blues Band as a kind of serious hobby. I was really glad I learned to play the blues on bass and guitar, because I was ready to fit right in to the Blues Revival that followed in the wake of the British Invasion 19.

I feel it important here to mention that Blues music—that quintessential African-American music form native to the USA—was being ignored by almost everyone in 1960. By 1964, though, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, The Kinks, Fleetwood Mac and other British rock stars revealed that the secret of their success was the Blues elements they cribbed from Americans like B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Elmore James, Little Richard, Sonny Boy Williamson, Gatemouth Brown and, of course, Mr. Crossroads himself, Robert Johnson. It was deeply ironic: White kids all over America were losing their minds over British musicians who credited, praised and emulated the Black originators of the music. I believe the homage musicians like Mick Jagger, Paul McCartney and others paid to their Black mentors added momentum to an American Civil Rights movement that sought to restore humanity and dignity (and commercial success) to many of those same individuals.

The summer before my senior year, I scored my first job, sweeping up the floors at Kassar Drug Store on Locust Avenue. It was, as advertised, a pretty menial gig, and while I was sweeping there was lots of time to think about what I really wanted to do with my life. I was already taking journalism classes at North High School with Mr. Barnett, and I was already Sports Editor for the North High Oracle. Importantly, I had also written some articles for the Iowa Bystander 20, the state’s most established newspaper for the African American community. Bystander editor Allen Ashby was my first mentor. He was a wise, knowledgeable man who prepared me well to go forward. So during the late summer 1967, as I was slinging the broom at Kassar’s, I thought that my experience might enable me to at least try to get a job at the Des Moines Register. I just remember thinking: “This is it. Go and at least ask about a job.”

I put the broom aside, checked out, and walked the four blocks to the Register & Tribune building. Once inside, I asked the receptionist where to apply for a job and she told me Fourth floor (while looking at me like she was thinking: “Sure kid, go on up…fat chance though…”)

Thanking her, I turned and walked through the lobby toward the elevators, noticing the huge, slowly rotating globe that displayed the time in every country. I also looked up to see the big, mounted panels displaying Pulitzer Prize winning stories, editorial cartoons and headlines. At that point in history, the Register and Tribune newspapers WERE the news sources all Iowa (and most of the Midwest) depended upon.

I got off the elevator, turned left twice and walked into a beehive convention in which activity was going off in all directions at once. I had happened to arrive just at Saturday afternoon’s sports deadline, where—it seemed—every living being who wasn’t playing football somewhere in Iowa was covering someone playing football somewhere in Iowa.

Sports Editor Leighton Housh was patrolling the writers’ desks where Bill Bryson Sr. 21, Buck Turnbull, Jim Moackler, and Ron Maly were racing toward their personal deadlines, pounding out stories on typewriters that emitted the ‘chik’ ‘chik-chik’ ‘chik’- sound of those old metal key-action Smith-Coronas.

Meanwhile, Bill Dwyre 22, Ron’s Maly’s brother Phil, Larry “Laddy” Paul and Copy Chief Howard Kluender were at the editor’s ring, heads down, pencils slashing through sloppy copy, replacing it with elegant, brief sentences, designed to be read over coffee in the morning edition.

When a break came in the action, Housh came over and took my application and asked me why I wanted to do this job, and what made me think I could.

I surprised myself with an almost immediate answer: I already was writing for my school newspaper, I really, really wanted to be a reporter, and I’d do anything to begin working there.

He took his pipe and switched it from one side of his mouth to the other, evidently curious. “Come back tomorrow,” he said, “And we’ll start you on the phones.”

Stunned, I stood there as it sunk in, thinking: Wait…he said…come back tomorrow…that means… I got the job!!

That moment validated everything I had ever been told by my family about the way opportunity would be open to you if you were prepared. The civil rights era was right on top of us then, and this gave me a certain amount of courage, I suppose, to go after what I really wanted. As I see it, moments like this one—where courage is what’s required, if we are going to step up and seize the opportunity when we have the chance—come to all of us sooner or later. Ethnicity has very little to do with it. Mine was a quiet triumph. In seeking an objective that I felt prepared to handle, I was confirming both parental guidance and personal observation of the way things could be.

Integration is a part of this time in my life: when I was hired as a coffee boy, sports phone desk person and copy runner, I was the only African American on the Register editorial staff.

Soon after I was hired, though, other African Americans followed: photographers Ron Bayles and (fellow North High graduate and NHS Hall of Fame Inductee) David Lewis came onboard, as well as the (great) feature writer (and another North High graduate) Elenora E. Tate. Each brought extremely high levels of professionalism to the job.

Another important milestone that I should note: after serving for a few months as coffee boy and copy runner, I was reporting on high school sports events and learning the ropes of general assignment reporting. On April 4th 1968, I was on the spot for the reporting break of a lifetime—which sadly, was connected to the death of a great American hero. Martin Luther King’s assassination was an earthshaking event, and in the wake of his murder Black communities across the nation erupted in rioting and what amounted to a communal scream of pain, anger and sorrow.

Des Moines’ Black community also ignited in violence that consumed the central corridor along University Avenue. I was in the sports department when I was approached by the city editor with a question: Would I be able to grab a camera and go to the area of the rioting to take pictures and report on what might be happening?

Protest against the Vietnam war in 1968, at Drake University

Before I knew it, I was stepping over fire hoses in the street, avoiding the police who were trying to keep order, and estimating the size of the groups of people who were either part of the action or observers. Martin’s death was a tragedy that I felt viscerally, but I was being given a chance to contribute to the reporting of a major news story. In later years, I learned that event was a sad but important launching pad for more than a few other Black journalists of that era, including the late Ed Bradley. After that night, I was moved to general assignment reporting covering stories including the Iowa legislature.

Thankfully, my faith in my ability to attain a job that I wanted was greater than my fear of being rejected. Racist messages, seeking to sow fear and doubt about people of color, were as strong then as they are now. Knowing about my family’s experiences in Iowa over the last 100-plus years, though, helped provide me with the perspective I would need to navigate a new world for which there were few road maps.

Looking back on it, I think the best thing about my time at the Des Moines Register was acquiring great research skills. The esteemed Iowa author Bill Bryson 23 and I both began working for the Des Moines Register while still in high school. His father, Bill Bryson Sr. was one of the nation’s great sports writers. Bill Jr. and I were high school-age copy runners and cub reporters learning the ropes, but we began a friendship that continues to this day. Those who love Bill’s body of work appreciate granular research combined with the wit of a happy sage. Bill began developing those gorgeous research skills whilst searching out obscure bits of information in the Registers’ vast archive of clip files in 1967-68.

The investigative reporter is the original Google. They never rest, and they never stop turning over rocks to find the truth. Learning where to look, whom to ask, and whom to “socially engineer” have always been the hallmarks of those who went out and got the story, and got it right. Pulitzer-Prize-winning writers like Nathan ‘Nick’ Kotz 24 and the Register’s own Clark Mollenhoff 25 were the kind of reporters that we need vastly more of today.

Anti-racism protest at Drake University in 1968

Then, in 1968, my journalistic worlds became a little too well integrated. Let me explain:

During my sophomore year at Drake, I was the sports editor of the University’s student paper, the Times-Delphic 26, while at the same time I was now a Police Beat reporter for the Register. As an 18-year-old, I was doing pretty well. I was getting lots of opportunities, and like a hungry kid at a banquet I was grabbing everything I could.

Late in the 1968-69 Drake Basketball season the Bulldogs were playing a pivotal Missouri Valley Conference game at Veterans Memorial Auditorium. Meanwhile, I was on police beat at the police station across the Des Moines River to the south and east of the auditorium.

I was monitoring the police radio, which was my job, waiting for something to happen. Meanwhile, the little AM radio on the shelf was tuned to the basketball game and crackling with excitement. WHO radio broadcaster Jim Zabel was going crazy as the Bulldogs were in a very close contest.

Man, how did this happen? I thought. I’m the Sports Editor; how come I’m up here at the cop shop, dammit?!

Well, as 18-year-olds will do, I decided to take a chance. I could leave the station, hightail it up to the auditorium, grab some of the action and take a few pictures for the next edition of the T-D. What could go wrong?

Well…upon my return to the copy desk after my shift at the station, I was asked how the game went? My attempt at playing dumb was unmasked by the fact that the game was broadcast on TV (duh?) and my face had clearly been visible among those on the sidelines. The press passes giveth and the press passes taketh away. Luckily there had been no murders, fires, robberies or even kittens up a tree during my absence, but my two-places-at-once act became office legend at the pre-Gannett Register.

The Wobble Begins

There was no doubt that my balancing act was getting to be a serious handful. Music, academics, a budding journalism career, the ever-present civil rights struggle and war worries were weighing on my mind.

It was also getting increasingly difficult for me to ignore internal questions about my absent father. Like that annoying small stone in your shoe, it wasn’t long before—one way or another—I was going to have to stop along the path to deal with it.

The tragedy of the Kent State Massacre 27 in May of 1970 triggered deep evaluation for me: Who was I, really? What was I doing here? Where else should I be? Why couldn’t I ever relax, and how could I regain equilibrium?

Like reviewing old movie footage, I began to replay my life looking for something to help me deal with something deep that I hadn’t dealt with previously. The more I concentrated, the more I began to remember events surrounding my parents’ breakup that I hadn’t allowed myself to revisit ever before.

At the time when a young man most needs the closest guidance to navigate the path into manhood, I was without my captain. Adding to the chaos, we were forced to move out of our house because of something called Urban Renewal 28. I learned that urban renewal was actually short hand for “build a big new freeway—over land formerly known as the Black neighborhood.”

Our little home, located at 1434 Walker St., was to be leveled to make way for the new freeway.

So: wow, first Dad is gone and now the city is telling us they can just take our house and offer compensation based on their assessment, not our asking price. Mom was able eventually to find us a new home in the Union Park neighborhood. Surprisingly, the move turned out to be a very cool thing, because instead of being held at a middle school, my new 9th grade classes convened at North High School, so I got to attend high school a year early. This wouldn’t be the last time a perceived negative would transform itself to my advantage. Flashing back to the present, I realize that attending classes at Drake was becoming burdensome because I simply had too many commitments and no time for rest or reflection.

As for Viet Nam—another stressor at the time—Mom hadn’t even wanted me to join the Cub Scouts so, the military was completely out of the question. As she told me with fire in her eye: “I’ll send you to Canada myself before I’d let them have you for that war!”

In an atmosphere of so much turmoil, I was really missing my father’s influence in my life. Telling myself that I didn’t care, or that it didn’t matter wasn’t working for me anymore. In the spring of 1969, I was sitting in my office at Drake when I had a revelation-like flash: I’m a reporter. I can find out everything else; why don’t I find my father? Wow! good question Dartanyan. What would a good reporter do?

I decided a good reporter would try the musicians’ union. I got the number for the New York Musicians Union Local 212, placed the call and asked: “Hello? Can you give me contact information for Ellsworth Brown please?”

“Just a minute…yeah we’ve got a number right here for you.”

Holy crap. I had my Dad’s phone number. Now the question was: “Do I reeeallly want to make the call?”

No longer able to quell the inner chaos that draped over me like a heavy overcoat, I dialed the number in hopes that some resolution might be gained from closing this long unresolved circle. Hearing his “hello” on the other end of the line, I felt like a salmon arriving back upstream to its spawning grounds. My father’s voice resolved the suspended chords of my life. I think we were both relieved that we were still alive and that positive energy seemed to attend our reunion. We filled each other in on some key points. Yes, Ellsworth was still a working musician, living on Staten Island. No, Dartanyan didn’t play a lot because he was in college, and working as a journalist.

That call was the coolest thing ever, and after it I updated my brothers Don and Kevan on the news. Reconnecting with dad was literally life changing, as all three of us would try, with varying degrees of success, to rebuild a relationship with Ellsworth and to make up for the time lost.

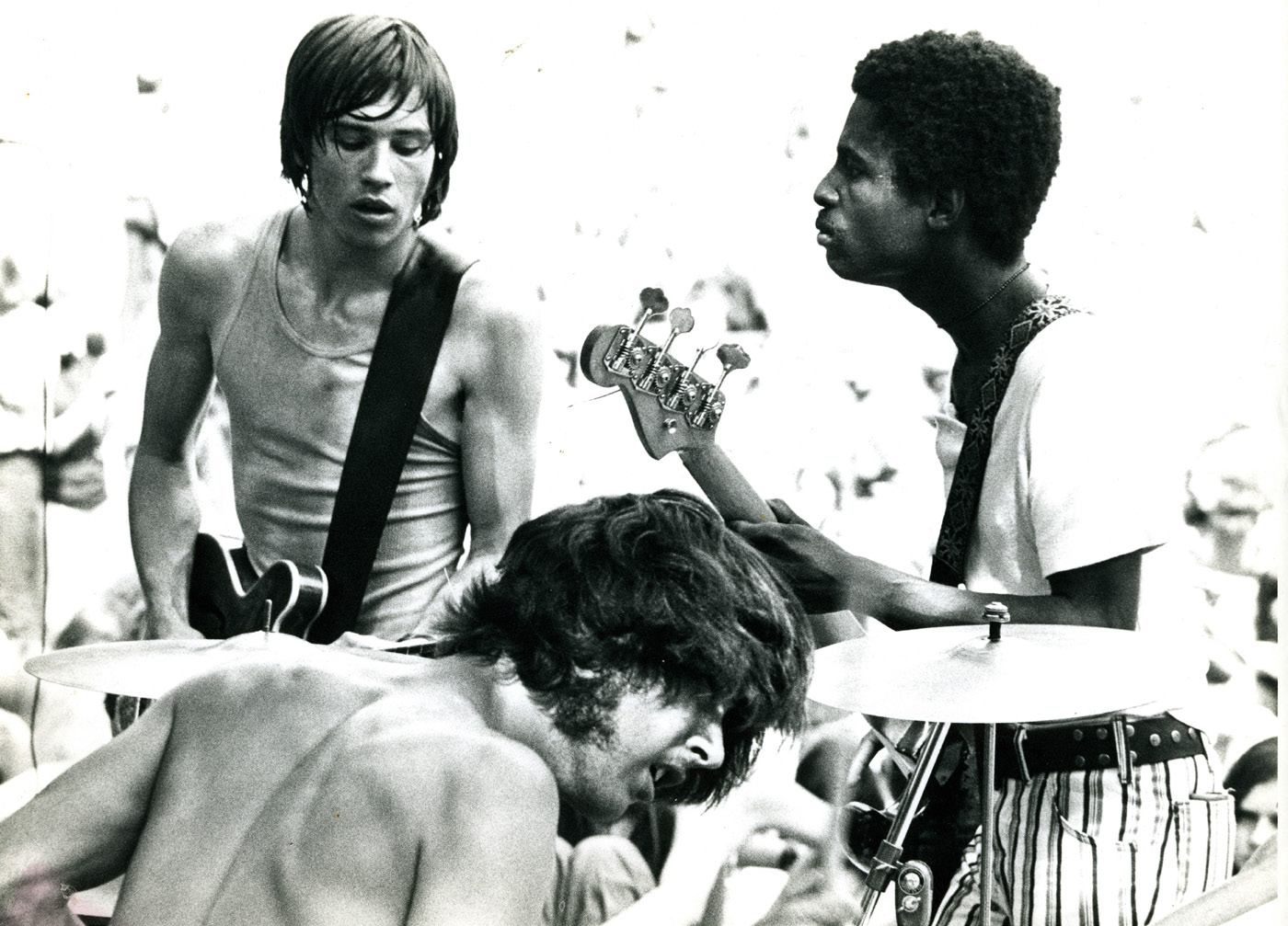

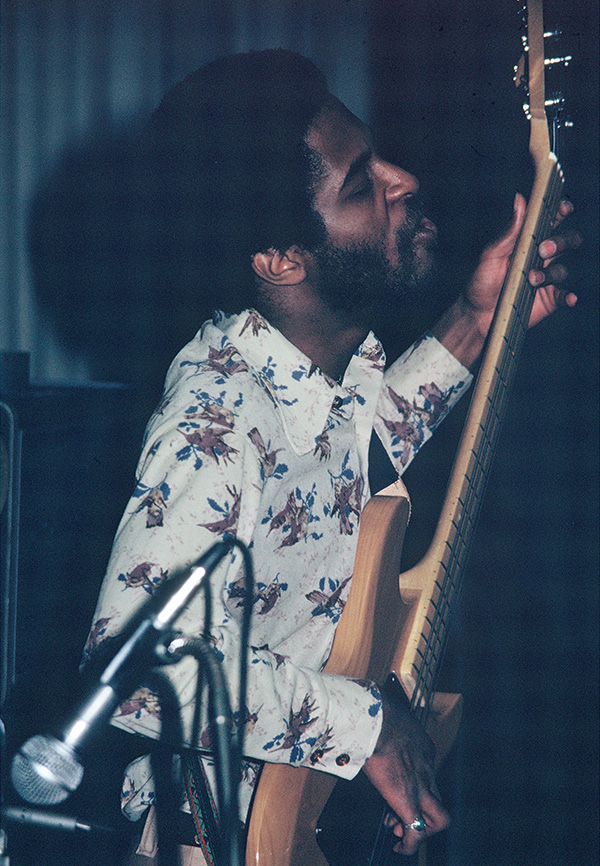

Wheatstraw on stage in Greenwood Park in Des Moines: Ron Dewitte (guitar), Dartanyan (bass) and David Bernstein (on drums). Photo by Bill Plymat

After the call, I resolved to go to NYC to see dad during my Spring break.

Our reunion was pretty crazy. We obviously had love for each other, but it was also obvious that, generationally speaking, we had developed very different views of the world. Example: I played electric bass and Dad thought all electric instruments were illegitimate. It was a great first meeting, though, and when it was time for me to return to Des Moines, I found out that, in addition to his music, Dad had high respect for German engineering. He was an excellent Volkswagen and Mercedes repairman, and gifted me with a Volkswagen bus from his small collection of vehicles.

Upon my return to Des Moines, I knew that my life trajectory was changing. Youthful frustration with the hypocrisy of the Viet Nam war was palpable. We intuitively knew that the government’s intentions were not what they were said to be. Our generation had to be both courageous and outrageous enough to look beyond the stories we were being told and to find out for ourselves how to enact our morals.

Trying to keep all of this balanced in my 19-year-old brain was causing burn out. My grades were going down, and staying up until 2 a.m. jamming with my musician friends wasn’t really helping me in classes. Something was going to give; I just wasn’t prepared for how it would happen.

I was spending more time playing with musicians in town and discovering where jazz, blues, rock, and even country players were jamming and experimenting. There were always adoring fans at these happenings.

Des Moines might have been Hicksville in some ways, but marijuana still found its way there just like everywhere else in the 60s. In fact, it was hard NOT to run into the plant during those days. I mentioned my tee-totaling folks earlier in this story and, of course, they had the same attitude about pot. While I wasn’t partaking (yet) it was always being offered...and I usually declined.

Well… and….

One time a gal offered me a half-smoked joint and I didn’t want to be impolite, so I took her half-smoked gift and stuck it in my billfold saying, “If it’s ok with you, I’ll save it for later.” Famous last words.

Busted

Later that evening, I was driving my newly acquired VW bus near campus when, all of a sudden, the jarring lights of a police car in my rearview mirror brought me to attention. In the best of times, Black guys don’t want to see flashing police lights in your review mirror. Upon request, I offered up my ID and waited for everything to be ok. I hadn’t gotten my permanent license plates for the bus yet…but I had the paper temporary permit, which was taped, to the rear window.

Well, he looked at my driver’s license, looked at me, looked at my license again…and then told me that I was under arrest!!?! He kind of grinned as he held up my driver’s license so I could see….something..stuck..on..my..license?!

Jeez, I mean, how often do you hand a policeman your driver’s license…with a marijuana roach stuck to it? While he held it out in front of me, I took a last desperate opportunity to ‘save myself.’ I grabbed the roach and stuck it in my mouth and swallowed it. He didn’t seem to know whether to laugh or hit me, but in that moment, my life passed before me and I knew it wasn’t going to be ok for a while.

Twenty years of building, working, preparing, praying and striving were (as I thought at the time) about to be completely wiped away. A roach no bigger than my fingernail blew up my life as completely as if I had set off a bomb. Which, in fact I had. Taken to jail, I had to call my mother to bail me out, and you can believe I’ll never forget the look on her face.

Of course, I went from covering the news to being the news in the worst way possible. The sense of shame was searing. The hopes and aspirations of many in my family and community were upended with my arrest for what amounted to the politically motivated machinations of Richard Nixon. Fifty years later, when in many cases we refer to marijuana as medicine, it seems a tragedy that he had the power to alter so many lives for a craven political motive.

To say I was forever scarred by the experience was understatement. The real, deeper lessons of the experience took some time for me to tease out of the chaos. At this lowest point in my life thus far, I was ready to chuck it all. As I was sinking, though, I was thrown a lifeline. It was called Wheatstraw….

In April 1970, musicians Ron Dewitte, Craig Horner and David Bernstein asked me to join their band, and since the band’s former bass player (whom I replaced) owned its former name, “The American Legend,” we’d have to find a new name. We were blues addicts at this time, and there was an obscure guy named Petey Wheatstraw. We thought that name (also on cigarette papers of that time) was funny, so we went with it for a band name.

Funny what joining a $90-a-week Blues band and leaving town will do for your crushed ego. I learned to care again. I started to care about myself and slowly dare to rebuild a value system. My searing sense of failure began to ease as I devoted many hours to practice, listening, analyzing and performing with my new band mates.

It was also a good thing that I was now actually communicating with my father. With his help, I eventually came to see that leaving college was a personal reset that put my life on a more sentient path. It sure beat going to Viet Nam to kill (or be killed) by folks I didn’t even know.

A symphony in brown crushed velvet: Dartanyan in Six the Hard Way after it morphed from Wheatstraw

Last Resort?

I might not have considered leaving everything behind to join a blues band if it hadn’t been for guitarist Ron Dewitte, who was eventually inducted into the Iowa Blues Hall of Fame with me in 2010. He was one of the most expressive blues guitar players I had ever heard. The touch, timing and fire that distinguished his playing rivaled anything I’d ever heard from anyone short of Jimi Hendrix. Craig Horner, our keyboardist and trumpet player, was also a fine musician who spent long hours practicing and listening to everyone from John Coltrane 29 to Jimi Hendrix. Importantly, I discovered that culture isn’t just about famous individuals. It’s what my friend, University of Indiana music professor David Baker, described as the Inner Circles vs. the Outer Circles. The marketplace needs “stars” (outer circles) for sure, but the real “capillaries of culture” (inner circles) are those local masters of community knowledge and custom who often remain unknown beyond their locality. So, while you may not have heard of Ron Dewitte, Craig Horner or David Bernstein, there was no doubt these guys dedicated their lives to expressing musical truth. Wheatstraw spent a fair amount of time on the road during 1970-72, playing the Midwestern states of Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois and Minnesota.

It was in Wisconsin that a new chapter was getting ready to begin for me, but I sure didn’t recognize it at the time.

The first time I heard Bill Chase 30 was when Wheatstraw was booked at Judy’s Gin Mill (!), a beer bar in Fond du Lac Wisconsin. It was a Friday afternoon and David, Ronnie and I were sitting around our hotel room doing basically nothing. Things were calm until Craig literally burst through the door (knocking over a nightstand in the process) and leaped to the record player. He took the record that was playing on the turntable and frisbee’d it across the room. Replacing it with one he held, he said: “You guys are NOT going to believe this...!”

And with that, we heard the first track of Chase’s first album entitled “Open Up Wide.…”

Once I peeled my brain off the ceiling, I researched Bill Chase and discovered he’d been a star trumpet soloist for big bands of the 60s, including Maynard Ferguson 31, Woody Herman 32 and Stan Kenton 33. Bill was a monster trumpet player and now he was a band leader whose first single (“Get It On”) would become an international hit song.

Hearing the album definitely changed my impressions of what music could be; but at the time, I had no idea that Chase’s music would literally reshape my life about 24 months from that moment. Wheatstraw toured for two more years, surviving until 1972, when in desperation we became Six the Hard Way (don’t ask...). Reality finally caught up to us, though, and I went back to Des Moines to write music and finish a journalism degree. Or so I thought…

When I returned to Des Moines after the Wheatstraw experience, I formed my first working group, called Dynamite. It was an extremely funky quartet featuring members Phil Aaberg on piano, Rod Chaffee on guitar, Tom Gordon on drums, and yours truly on bass guitar. A band of writers, we played bluesy-jazzy roots music that morphed from one style to another with great relish. Our influences were as wide ranging as John Coltrane, Paul Butterfield, John Cage 34, the group Tree (an Iowa City Free Jazz collective), Donny Hathaway 35 and the Sons of Champlin 36.

Dynamite was a fun band with talent to burn, but unfortunately for us (though fortunately for my future), through a connection to the Kansas band The Fabulous Flippers 37, our drummer, Tommy Gordon was called up to the “big time” to play with…Bill Chase!! (Chase’s second album, “Ennea,” had been released a few months earlier). Tommy was a great drummer who rightly jumped at the chance to play with Bill. Of course, that meant the end of our great little Des Moines band but things were far from boring…

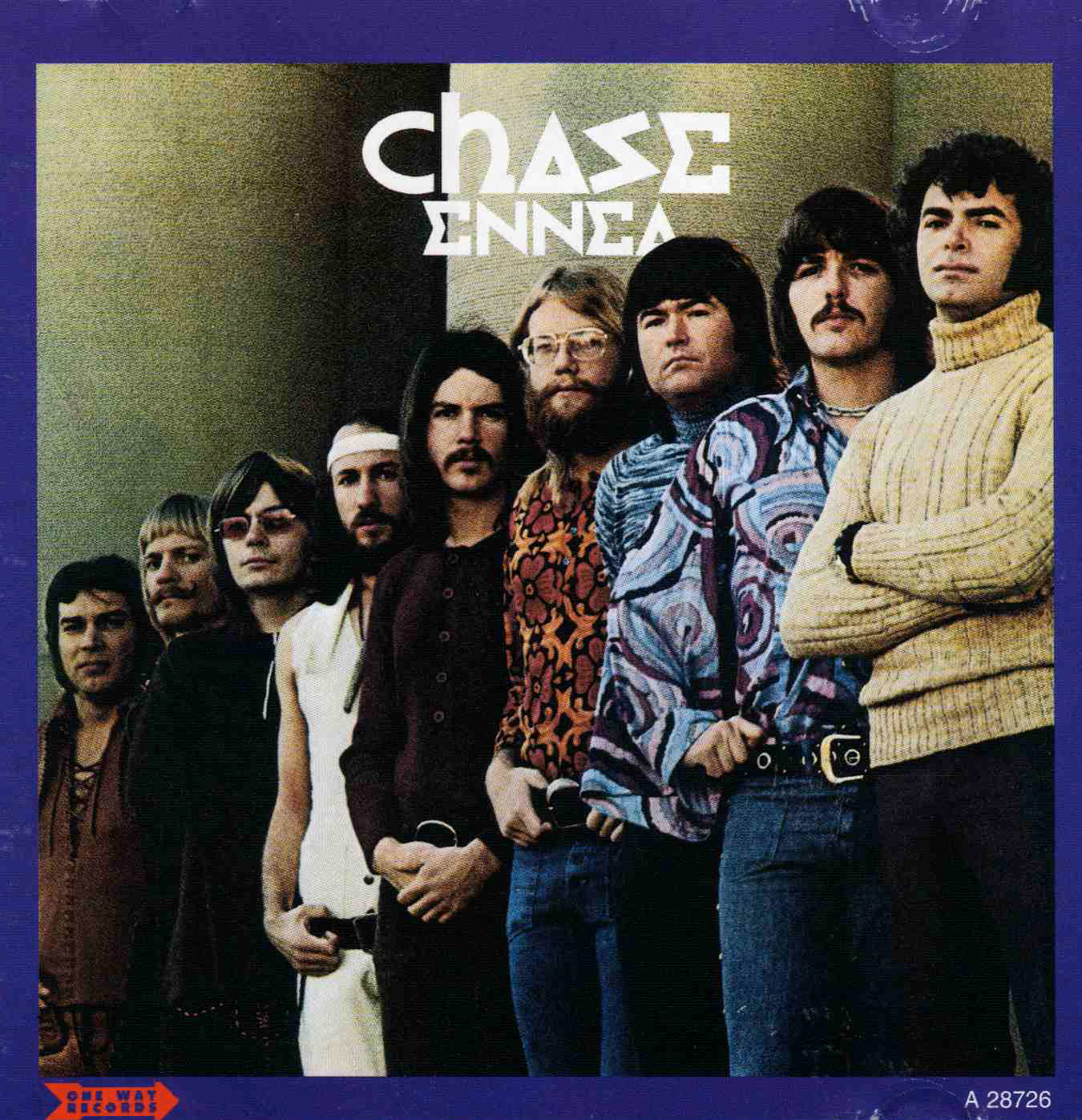

Chase’s second album “Ennea” came out not long before Bill Chase called Dartanyan up to the big-time

After Tommy left town, I collaborated with John Rowat, Bill Jacobs and Michael Schomers to start a band called The Mothership. It was another more experimental band with jazz/rock/country influences. We had a band house on the SE corner of Des Moines on Army Post Road. Next door to our house there was a big roadhouse called the 505 Club (which everyone called “The Five.” It was notorious as what I would call a “cowboy punch out” bar. It was a rough joint, but the music that got played in there was worth the risk of injury or dismemberment.

The Five was owned and managed by Dick Kampus, a large and hearty man with a real lust for throwing a party, The Five was the classic edge-of-town bar which even the local police didn’t mess with too much because it was that rough.

Over the years, we saw lots of different groups there. Funky horn groups like the previously mentioned Flippers, singer Marvin Spencer 38, and lots of groups from Kansas, Florida, Louisiana and elsewhere. The list of bands that toured the roadhouse circuit to carve out a career is long. I was at home next door to the club when one day the phone rang…

I picked it up. " Hello," I said.

“Hey Dart,” said the excited voice on the other end, “Get your ass over here now and hear this...!” I recognized the voice as Dick’s from across the driveway at the Five.

“What are you talking about, man?” I queried.

“Just get over here NOW, you won’t believe it.”

As I loped across the expanse of white gravel, I heard the rhythmic thud of bass guitar and drums coming through the walls of the club. As I got closer to the door, the syncopation was getting “too good” if you know what I mean. By the time I entered the cavernous club, it only took another two or three minutes to realize that something special was happening on the stage—and this was just rehearsal.

The group rehearsing for the evening’s show was Wayne Cochran and his band, the CC Riders 39. For those of you unfamiliar with the tradition, Wayne Cochran was a White soul singer in the tradition of James Brown. The cool thing about Cochran was that he, like Brown, was the real deal. He was a loud, signifyin’, funkified White boy who could drive an audience as well as any R&B veteran I ever saw. But I digress…

Cochran’s energy emanated as much from his band as from his own nasty soul. The band’s engine was being stoked by a tall skinny kid on bass who they called Jaco.

“Jaco” was Jaco Pastorius 40, later bass player for Weather Report 41, which—alongside Miles Davis’s 42 electric bands, the Mahavishnu Orchestra 43, Return to Forever 44, and Headhunters 45—was one of the most important jazz fusion bands of the 70s and 80s. When I saw him at the Five, though, Jaco was the heart of Wayne Cochran and the CC Riders’ rhythm section, which also included guitarist Charlie Brent. (As a side note, Brent—a dynamite arranger—would later contribute charts to Bill Chase’s second album, “Ennea.”)

Well, I listened transfixed as I watched Jaco creating totally loose, but on-the-mark bass grooves. His sensibilities for groove and support and melodic bass playing were strangely scary, but at the same time an affirmation of where I knew the instrument could go.

After the rehearsal, I made a beeline for the stage and introduced myself to Jaco. Being an old newspaper reporter, I wasn’t going to miss an opportunity to “interview” this guy to find out where he got his bouncy, funky style.

I offered our house next door if he wanted to hang out with us, and for the next 3 days I played host to the Future Of Jazz Electric Bass! We jammed, talked, went to the Cochran gig, then jammed some more, talked a lot more about life, our families, Miles, and why each of us had a lot to offer. I have never met a more honest, caring, sensitive and talented individual than Jaco Pastorius in 1972.

While Jaco was a natural musician whose father played drums, he’d also studied with Ira Sullivan 46 at the University of Miami 47. His mom Greta was someone he was totally devoted to. Jaco already had a young family then, and it was his single-minded goal to support his family by convincing everyone that he was the world’s greatest bass player!

He was convinced of that fact (I certainly wasn’t going to disagree, based on what I had heard) and he told me of his plans to leave the Cochran band soon and travel to Boston to join up with a new friend named Pat Metheny 48. Metheny, he said, offered him an opportunity to teach at Berklee College of Music 49 in Boston. In 1976, Metheny—who was then only 21—would make his seminal debut recording “Bright Size Life” 50 on ECM with Jaco. Later in 1974, Pastorius and Metheny joined pianist Paul Bley and drummer Bruce Ditmas to record an album on Bley’s Improvising Artists 51 label).

Anyway, the three days spent with Jaco could only be termed as a meeting of kindred spirits. The next time I saw him was 1976 at the Newport Jazz Festival 52. By then he was with Weather Report and a true star. The best thing was, when I saw him again, he actually spotted me at the back of a large auditorium (Alice Tully Hall, I think) as I was walking in for Weather Report’s sound check.

From the stage, he saw me (barely visible I was) and yelled at the top of his lungs “Hey DARTANYAN, HOW YA DOIN’.” It was a testament to his eyesight, his memory and his heart that he actually remembered our time together after HIS life had changed so radically.

One sad note: The Jaco I knew in 1972 was on a natural high of life. He neither smoked, nor drank, nor even talked about anything but the most inspiring subjects. His goal was to play with Miles Davis. Period. He knew he was good enough, musical enough, and hip enough and that was that!

I never saw Jaco again after Newport. Back in 1972, he had told me that he had a chemical imbalance that meant his sensitive system could not tolerate most drugs or any alcohol. Moving to NYC was probably the worst thing he could have done because the influences on him at that time were uniformly bad. Every time news came in about him it was usually great professional triumph but leavened with the sad news of his descent into drug and alcohol abuse. Still, I’ll always have memories (and the tapes) of the Jaco Pastorius I knew, who propelled Wayne Cochran and the CC riders in ‘72. Bless you Jaco.

Dartanyan sailing on stage when he was a member of Chase

Back to Bill…

It was now spring ‘73 and, as I mentioned earlier, Tommy Gordon, our drummer in Dynamite, had already joined Chase through his Fabulous Flippers connection. Former members of that group were touring with Bill touring in support of the “Ennea” album, so Tommy’s connection from years earlier had paid off. It was about to do the same for me.

I was in my kitchen making a sandwich when the phone rang.

I picked it up with my mouth half-full and almost choked when the voice on the other end said. “Hello, this is Bill Chase.”

Needless to say, I was nervous and incredulous as he laid out his offer.

“I’ve been looking for a new bass player and Tommy says that you’re a great bass player and a singer too.” I didn’t quite know what to say except to try to agree without sounding too egotistical (unlike my friend Jaco, who would have had no problem promoting himself).

“We have a tour due to start in El Paso, Texas in two weeks,” Bill said. “Do you think you can make the gig?”

He asked me if I knew the music and I said that I knew the first album from listening, but that was it. He said, “No matter, we’ve got all the charts.”

I just said a little prayer of thanks that I was playing in the Drake University Jazz band with Bob Weast 53. Taking two semesters of Jazz Band had given me exactly the foundation I needed to read the charts I lived with for the next 17 months.

Talk about bittersweet…

I had just signed a lease with my friends in Des Moines to secure our band house and now was I going to leave town?

My band mates, John Rowat, Michael Schomers, Frank Tribble and Bill Jacobs, were more supportive of me moving up than they were disappointed at losing a renter, so I was off to Chicago to begin what would be life-changing circumstances.

Dartanyan onstage with Bill Chase

3 https://www.facebook.com/The-Original-Buxton-Iowa-Club-INC-276779099055023

4 https://www.allmusic.com/artist/frank-perowsky-mn0000174141

5 https://reverb.com/item/6878309-wilcox-gay-recordio-model-6a1ou-record-lathe-vintage-antiqueturntable-cutter

6 http://cibs.org/events-programs/iowa-blues-hall-of-fame/speck-redd

12 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operating_Manual_for_Spaceship_Earth

13 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Captain_Video_and_His_Video_Rangers

18 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Resurrection_of_Pigboy_Crabshaw

38 https://wcfcourier.com/entertainment/local_entertainment/marvin-spencer-had-golden-voice-personality/article_d361cf5b-d1ce-59ae-b110-bc8c4790b71c.html

53 http://dmcommunityjazzcenter.org/HallofFame/tabid/86/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/27/Robert-Bob-Weast-2007-Inductee.aspx