Snow trillium (Trillium nivale) or dwarf white trillium, is a member of the Melanthiaceae family, and is native to parts of the Eastern and Midwestern United States, primarily the Great Lakes States, the Ohio Valley, and the Upper Mississippi Valley. The species is one of the earliest flowers to bloom in spring. Along the Ohio River Valley, flowers may be seen in early March, while in Northern Minnesota, it blooms in early April. All photos, unless otherwise credited, are by Cornelia Clarke. All text descriptions are adapted from Wikipedia and The State Historical Society of Iowa

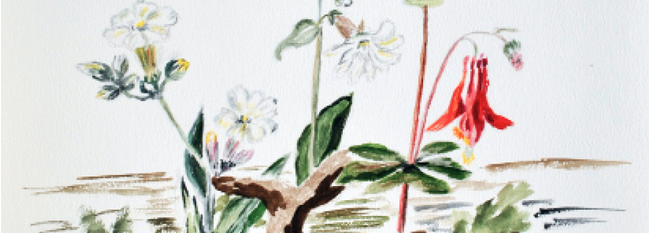

Recently, and quite by chance, Rootstalk became simultaneously aware of the work of two women artists, born in Iowa two years apart toward the end of the nineteenth century. Cornelia Clarke (1884-1936) and Lydia Krueger Curtis (1886-1973) had rather different life experiences, but both felt drawn to the wildflowers of the tallgrass prairie, which during their lifetimes virtually disappeared from the Iowa landscape as the result of agriculture. Both were moved to record the beauty of prairie plants, Clarke through the medium of photography and Curtis in watercolors. We thought our readers might enjoy the juxtaposition of Clarke’s and Curtis’s art as much as we do.

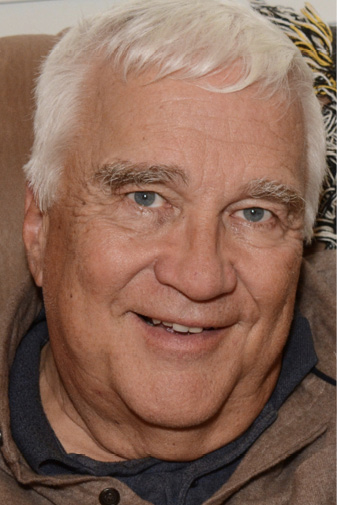

Cornelia Clarke (1884-1936)

Photo courtesy of State Historical Research Center of Iowa

Cornelia Clarke was the only child born to Ray Alonzo Clarke (1850-1932) and the former Cornelia Shepard (1849-1884), July 4, 1884. Her mother died within a few hours of the baby’s birth, so Cornelia was “baptized over the coffin with her mother’s name,” as her mother’s obituary had it. At the time, her father was farming north of Grinnell, Iowa, and, except for her father’s mother, who came to Iowa to keep house and care for the baby, Cornelia lived a fairly lonely childhood, occupying herself with the animals and plants she found around the farmstead. These early experiences with the natural world proved crucial to her life-long interest in nature and her ability to photograph it.

Clarke learned the rudiments of photography while still a child, borrowing her father’s camera and gradually developing her skill. While still quite young, she began to photograph her pets, including two cats, which she trained to accept humanoid clothing and to pose like humans. These pictures were first published in 1911, bringing Clarke immediate fame and a contract to publish colorized versions in a fetching 1912 volume, Peter and Polly.

“My childhood days were spent on a farm with father and, not having any brothers or sisters, my mother having died at my birth, perhaps the cats took the place of many things which other children have…My cats and myself were brought into a closer understanding and a sort of deeper affection grew between us.”

However, if many of Clarke’s early photographs required an imaginative story as context, over time she became a serious nature photographer whose pictures appeared regularly in publications like Nature Magazine and Science News-Letter, the latter often using Clarke photos for its covers. Numerous authors of biology and zoology textbooks also sought her photographs, as did encyclopedias and newspapers.

Clarke used her growing camera skills to reveal the secrets of biological process, as when she documented the life history of the mosquito or the stages of butterfly generation. Collaborating with Grinnell College professors like Henry Conard (1874-1971) gave her occasion to produce images—often enlarged many times over natural scale—of great scientific accuracy and value, confirmed by the Grinnell College herbarium of local plants of which she became volunteer curator.

Despite her success, Clarke’s last years were not happy. Difficulties began when in May 1929 she and her father were involved in an automobile accident. Both suffered from the collision, and Ray “slowly but steadily failed until the end came peacefully,” March 21, 1932. Cornelia carried on, and continued to publish her photographs, but soon after her father’s death she was diagnosed with breast cancer, which killed her September 29, 1936. She bequeathed some 3300 glass plate negatives to Henry Conard, who abandoned them at the University of Iowa when he retired in the 1950s. Fifty years later 1100 of her botanical images were discovered in poor condition, but saved by the State Historical Society of Iowa. The fate of the other 2200 negatives—of insects and animals, including cats—is unknown.

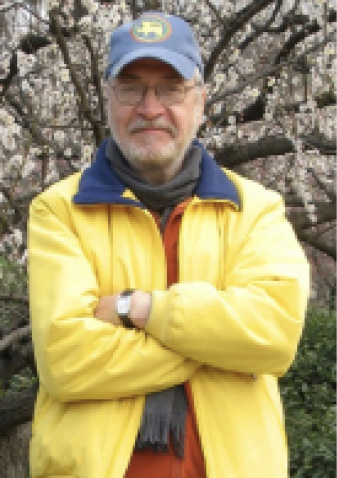

—Daniel Kaiser

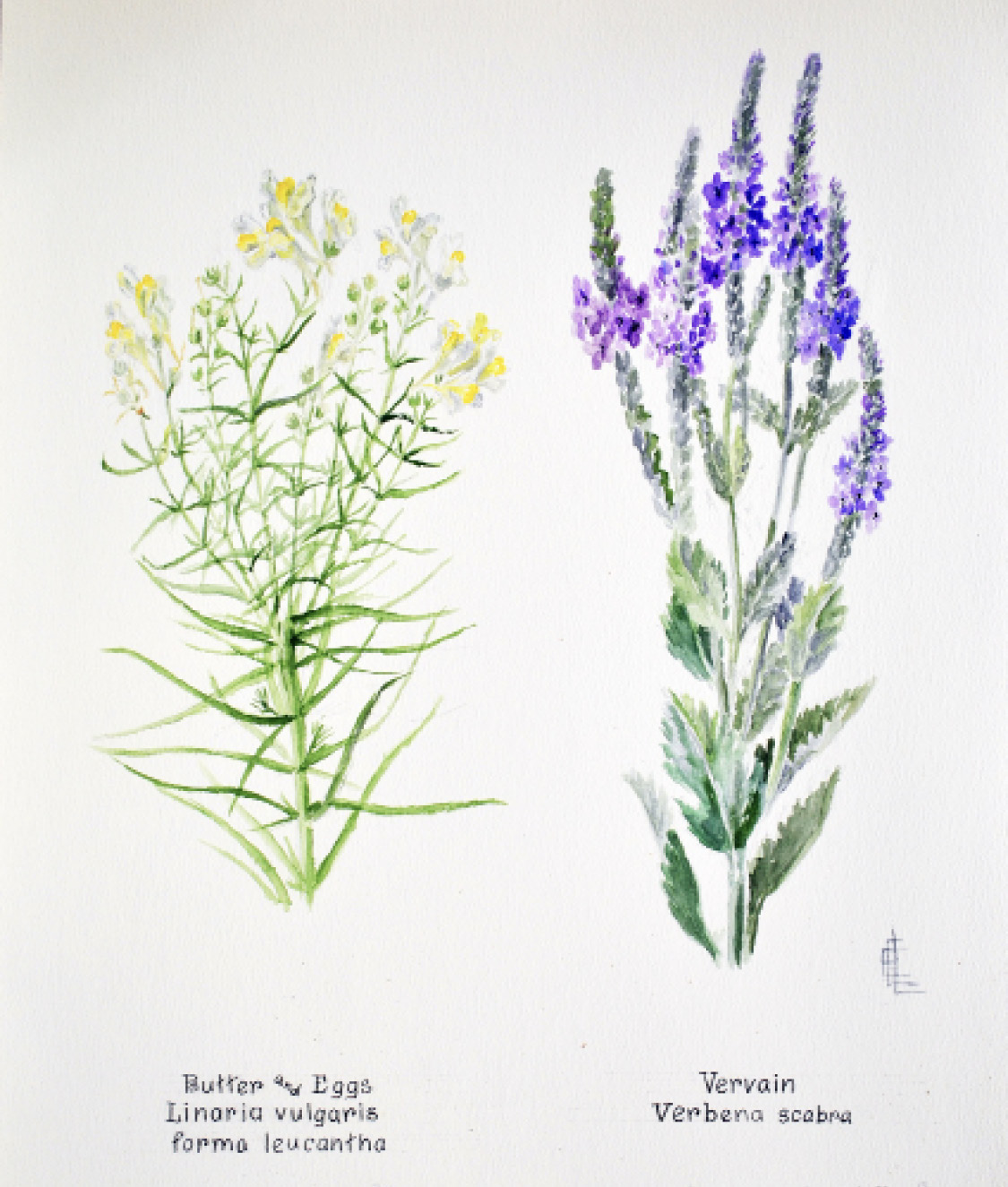

Butter and Eggs

Linaria vulgaris

This plant with its bright blossoms used to be easily found but now it is not often seen. It grows from one to three feet tall, and grows from short root stocks. Where found it may be in clusters or a colony of plants. It has been naturalized from Europe.

It was believed to have certain healing powers. The blossoms have been steeped and used in cases of dropsy, jaundice and various skin infections. The fresh plant has been bruised and applied as a poultice on boils and was also made into an ointment that was used for skin irruptions. In Germany the blossoms were used as a yellow dye. Pioneers used the juice in milk as a fly poison.

The blossoms resemble the cultivar Snap Dragons in shape and manner of growth. They are visited by bumble bees and butterflies.

The plant is partially parasitic. Its roots wrap themselves around any roots—even other roots of the same plant—that chance to be near, and draw part of their food from their host.

Sandpaper Vervain

Verbena hastata, var. scabra*

This is a hardy plant that came to us from Europe. It is also known as Wild Hysop. In Europe it was one of the religious plants of the Druids. In ancient times it was held sacred to Thor, the god of thunder. It was used to stimulate affection and charms and was reputed to break the power of witches.

In France it was gathered under certain changes of the moon with secret incantations, after which it was supposed to make remarkable cures.

Bridal wreaths made of Vervain were used in Germany. Both Virgil and Shakespeare mention Vervain in their writings.

When found in dry hilly pastures it is small and the stems are tough and woody, but in moister more fertile ground it grows luxuriantly.

Indians gathered the seeds and made them into flour.

Pasque Flower (Anemone patens Wolfgangiana), also known as Prairie Crocus or Cutleaf Anemone, is a member of the Ranunculaceae family, and is one of the first flowers to bloom in the spring, often coming up while there is still snow on the ground. Look for it on south facing slopes in dry to average sandy soil, typically in scattered clumps. All these photographs were most likely taken in or near Grinnell, Poweshiek County, Iowa, early in the twentieth century.

Canada Anemone (Anemone canadensis) is another member of Ranunculaceae family. Also known as the round-headed anemone, meadow anemone, or crowfoot, it is a herbaceous perennial native to moist meadows, thickets, streambanks, and lakeshores in North America, spreading rapidly by underground rhizomes, valued for its white flowers.

Lily-of-the-Valley (Convallaria majalis), also known as May bells, Our Lady’s tears, and Mary’s tears, is a rhizomatous herbaceous perennial of Asparagaceae family. It is a sweetly scented, highly poisonous woodland flower, native throughout the cool, temperate Northern Hemisphere. It flowers in late spring, though in mild winters it has been known to bloom in early March. The plant’s variant, majuscula, is thought to be native to North America.

Asclepias (milkweed) seeds. The Asclepiadaciae family is a genus of herbaceous, perennial, flowering plants named for their latex, a milky substance containing cardiac glycosides termed “cardenolides,” exuded where cells are damaged. Most species are toxic, though the plant is vital as a food source for the caterpillar of the monarch butterfly. The genus contains over 200 species distributed broadly across Africa, North America, and South America, and includes several species which are native to the prairie region.

Wild Geranium (Geranium maculatum) in its fruit capsule stage. In this phase of its development, the flower resembles a crane’s bill, which accounts for its “Cranesbill” nickname.

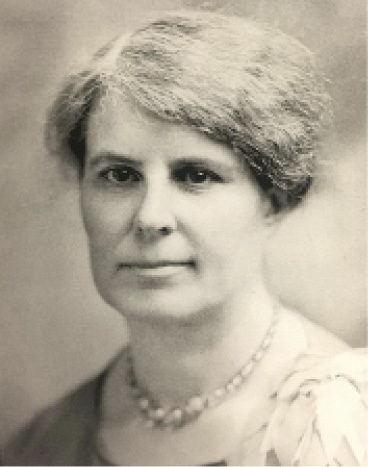

Lydia E. (Krueger) Curtis

Photo courtesy of State Historical Research Center of Iowa

(1886-1973)

Lydia Krueger Curtis was the second of four daughters born to Fred and Sophia Krueger. She grew up on a farm southwest of Charles City, Iowa, and graduated from Charles City High School. Her older sister wrote the following about life on their farm:

“The near-by timber was an ideal locale for little girls to grow up and learn to know birds, flowers and trees. Our parents knew and loved wildlife. Our father was a born naturalist. No plant, stone, tree or bird escaped his notice. A tramp through the woods was fun and we always learned something new from his knowledge about nature. In the spring, we strolled along the creek into the woods where bloodroots, bluebells, Dutchmen breeches and violets grew in profusion. Sometimes we picked flowers until we could carry no more. Our mother patiently untangled our armfuls and showed how they must be put into water. She told us not to pick so many because some must be left for seed…a lesson in conservation to avoid the destruction of the beautiful wildflowers of our childhood.”

Lydia received a bachelor’s degree at Highland Park College in Des Moines, where she met James Hubert Curtis, whom she married on December 27, 1910. While earning her bachelor’s degree, she also taught pen arts at the college.

As a civil engineer, James was employed in Iowa, Minnesota and Missouri communities. During their marriage, Lydia carried on the usual activities of a wife and mother, as well as church, school and community activities. During the Depression she augmented family income by extensive gardening and raising poultry. She also found time to engage in painting with watercolors and oils, something she enjoyed since girlhood. Her talent was recognized early by her father, who arranged private lessons while she was still in her teens, though in large part she was self-taught.

Following James’s death in 1945, Lydia worked for the United States Army Corps of Engineering. Her responsibilities included using field data to hand-draw snow pack maps of the upper Missouri River watershed to estimate spring run-off.

After retiring at age 72, she had the leisure to give full rein to her artistic talents, her love of flowers and more-than-superficial knowledge of botany. She searched out, collected and painted in watercolors the wildflowers indigenous to the upper Middle West, especially Iowa and Minnesota. During the twelve years she continued painting, she produced about 250 plates of different wildflower species. At age 85, with failing vision and a less than completely steady hand, she quit painting, concluding she no longer could “do justice to the beauty of the wildflowers.”

Still, she kept working on precise identification of each species. Her knowledge of botany was used as she keyed out each species with the best technical manuals as reference. Also, she accumulated bits of lore about the flowers, including where they might be found, the preferred soil and growing conditions, whether they were edible, their use as herbs in cooking, or as sources of medicines by the Indians or by pioneers. She incorporated this into essays to accompany her paintings, and we reproduce them (in part) here.

—Andy Hayes

Butter and Eggs

Linaria vulgaris

This plant with its bright blossoms used to be easily found but now it is not often seen. It grows from one to three feet tall, and grows from short root stocks. Where found it may be in clusters or a colony of plants. It has been naturalized from Europe.

It was believed to have certain healing powers. The blossoms have been steeped and used in cases of dropsy, jaundice and various skin infections. The fresh plant has been bruised and applied as a poultice on boils and was also made into an ointment that was used for skin irruptions. In Germany the blossoms were used as a yellow dye. Pioneers used the juice in milk as a fly poison.

The blossoms resemble the cultivar Snap Dragons in shape and manner of growth. They are visited by bumble bees and butterflies.

The plant is partially parasitic. Its roots wrap themselves around any roots—even other roots of the same plant—that chance to be near, and draw part of their food from their host.

Sandpaper Vervain

Verbena hastata, var. scabra*

This is a hardy plant that came to us from Europe. It is also known as Wild Hysop. In Europe it was one of the religious plants of the Druids. In ancient times it was held sacred to Thor, the god of thunder. It was used to stimulate affection and charms and was reputed to break the power of witches.

In France it was gathered under certain changes of the moon with secret incantations, after which it was supposed to make remarkable cures.

Bridal wreaths made of Vervain were used in Germany. Both Virgil and Shakespeare mention Vervain in their writings.

When found in dry hilly pastures it is small and the stems are tough and woody, but in moister more fertile ground it grows luxuriantly.

Indians gathered the seeds and made them into flour.

Gold Star Grass

Hypoxis hirsuta

Gold Star Grass [also called yellow star grass or common goldstar] belongs to the Amaryllis family. Its leaves look much like the grass leaves that grow around them in both size and shape, but they grow from a small bulb.

The blossoms grow on very slender stems from the bulb with the leaves surrounding them for an inch. The blossoms have three sepals and three petals, all bright yellow on the face and lighter yellow or somewhat green on the back. The blossom opens to about a half inch. There are several buds which form at the tip of the stem, but they usually open one at a time.

Prairie Lily

Lilium philadelicum, var. andinum

The Prairie Lily [also commonly referred to as the western wood lily] seems to belong to the prairies of the Upper Midwest of the United States. I have failed to find anything about it in any of the Eastern or Western flower books. Even Ryberg in his book Flora of the Plains and Prairies of the United States does not mention it. In Gray’s 8th edition of his Manual the author does add “var. andinum-which grows in the prairie” to his paragraph about Lilium philadelphicum, the wood lily.

When I was a child there were still large areas of unfenced prairie near our home. My father rented tracts of this land to pasture cattle. He hired a young man to herd the cattle. At intervals during the summer he drove out to see about the herder and cattle. Sometimes he took my sisters and myself with him. In June and early July we would find the prairie bright with flowers. Among these were the bright red Lilies. How we prized them.

The Prairie Lily [has] a simple stem about 15 inches tall, which ends in a whorl of leaves about 1-1.5 inches long…. The leaves are fleshy and narrow and below the whorl they alternate on the stem. The blossoms are more orange-red than the Wood Lily’s crimson. Like other lilies they fasten to the stem with narrow parts of the petals and sepals, then abruptly widen and grow more colorful. Near the place of widening they are spotted with small purple spots. The blossoms do not open as widely as those of the Wood Lily but instead the petals and sepals stay more upright. The stamens and three-part pistils are pink tipped with brown which adds much to their beauty.

Since prairies are cultivated and roadsides mowed, these beauties are becoming rare.

Stiff Marsh Bedstraw

Galium tinctorium*

Marsh Bedstraw with its whorled leaves and plumy heads is very attractive. In this area there are several varieties; in fact they are widely distributed. They grow from fibrous roots. Indians used the juice from these roots to dye their feathers and themselves. Just how they got the name Bedstraw I have not been able to learn. One variety is fragrant, especially when dry. It may have been from this variety.

White Campion

Lychnis alba

The Campions belong to the Pink family. They have ovate-lance shaped leaves. Both stem and leaves are softly hairy and sticky. The corolla petals are held in a tubular calix which becomes inflated and red- ribbed as it matures. The outer part of the corolla spreads out to make a blossom 1-1.5 inches wide. The blossom is centered by stamens seated in the tube, the yellow anthers barely showing above the surface of the corolla.

The white Campion has many species, and they are widely distributed in Minnesota. They may be found in many waste areas. The one sketched was found near Gull Lake northwest of Brainerd, Minnesota.

Columbine

Aquilegia canadensis

In shady nooks or along stream banks the stately Columbine finds its favorite home. The lower leaves are long stemmed and compound with subdivisions in groups of three. Simple notched leaves surround the stem at points where the stem branches. The slender red-brown stem grows tall, usually rising above neighboring foliage at blossom time.

Although delicate in appearance this is a hardy plant. The lower part of the stem is stiff and almost woody. The stem may branch several times, each branch terminating in the red and yellow blossoms which hang gracefully. These blossoms have a unique form, consisting of five yellow sepals—which look like petals—and five tubular petals which point upward. These petals have small sacs of honey at their tips especially attractive to hummingbirds. These dainty visitors add their color and charm. (When I was a child I and my sisters used to enjoy nibbling these tips.) A group of long yellow stamens and slender pistils hang like golden tassels from the center of the blossoms.

In Colonial days plants of Columbine were sent from Virginia to King Charles I to decorate the gardens of Hampton Court.

The Columbine is widely distributed in the wooded areas of the Midwest. The speciman sketched was found in the woodland near Gull Lake northwest of Brainerd, Minnesota.

Virginia Bluebell

Mertensia virginica

In the long-ago when I was a child my family lived near a creek that meandered its way through a woodland. At its bends were a number of low moist areas, so-called bottom land. In May or early June we found these areas so blue they looked like pools of water. As we ventured near we found it was Bluebell time and that the bright blue Mertensias or Virginia Bluebells were in bloom. The beauty of the Bluebells and their fresh fragrance were always a special delight.

The plants grow from one to two feet in height. The leaves are rather large, oblong in shape, smooth in texture, easily crushed. When the buds first appear they are a delicate pink. As they continue to develop they become a dainty orchid color and finally clear blue.

Although these plants are hardy and respond readily to being transplanted to cultivated gardens, they have not been able to endure the tramp of cattle over their natural beds. The sight of large patches of Bluebells such as I knew is becoming rare.

This plant is known by various local names such as Cowslip and Lung wort.

The specimen sketched was growing in our wild flower garden in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Prairie Smoke

Geum triflorum*

This lovely prairie flower, once so plentiful, is known by several names such as Torch Flower, Plumed Avens and Old Man’s Whiskers. It cannot survive cultivation and frequent moving. Now that the virgin prairies are mostly cultivated it is becoming very rare.

Many years ago when I was a little girl we lived in north central Iowa in an area between a large native prairie and some timberland. The prairie was not fenced and farm homes were far apart. My father rented some of the prairie land and hired a man to herd cattle on it. Sometimes he would drive out to see how the herdsman and cattle were doing. Frequently he took me and my sisters with him. In June and July we would find patches of Prairie Smoke growing in the grass. We were always delighted to find these flowers so different from most plants.

At the base of the plant there is a roseate of attractively notched base leaves three to six inches long. They are broader at their tips than near the base. From this base almost naked ruddy red stalks arise which are divided into three branches. The branches are terminated by ruddy red buds. As the blossom opens the white petals are small and insignificant, but there are an abundance of pistils which grow into a hairy head with numerous hairlike appendages. These are delicately colored and make an unusual showing with the ruddy sepals surrounding them and the ruddy stems holding them to the wind. From a distance they give an impression of a cloud or smoke, hence the common name of Prairie Smoke. In some area they are known as Old Man’s Whiskers.

The specimen sketched was found in a bit of prairie turf a short distance south of the Minnesota-Iowa border near Chester, Iowa.

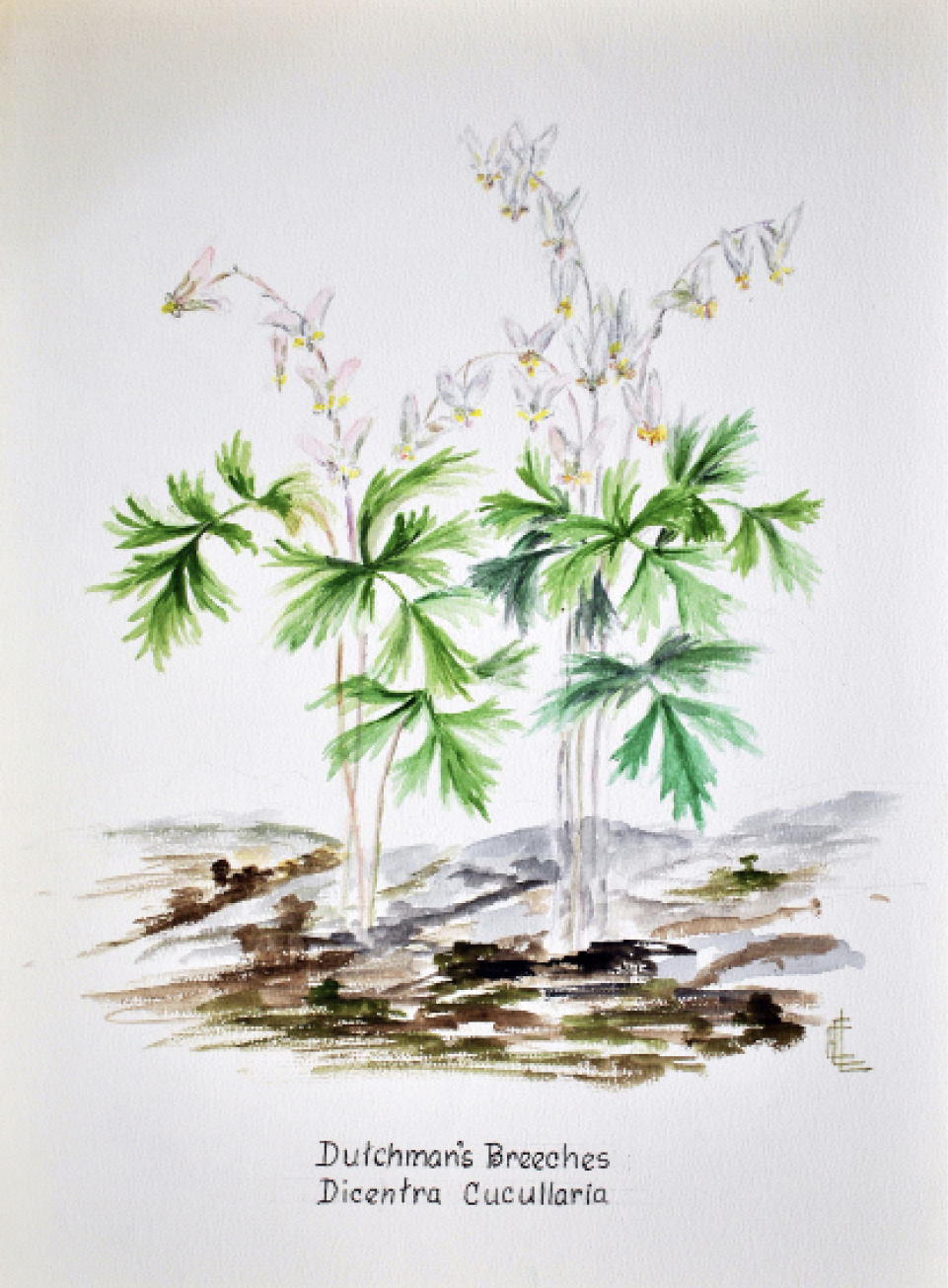

Dutchman’s Breeches

Dicentra cucullaria

This is one of our daintiest wild flowers. It blooms in May in our area, preferring a wooded lake shore or streamside. The leaves are compound, being divided into parts of three until they are lacy. Both leaves and blossoms grow on long stems which grow up from a cluster of small tubers which look like a scaly bulb.

The blossoms have four petals, two of them formed into pouches joined together so they look like pantaloons. Since they were found by our colonists in New York and eastern Pennsylvania they were given the name of Dutchman’s Breeches, probably because they resembled the garments that Dutch men were then wearing. At any rate this name followed them as people moved on westward. The blossoms are mostly white but sometimes a very faint pink. The other two petals are small and are shaped like a cup, protecting the stamens of which there are six.

Squirrels are fond of the bulbs and when other food is scarce they will dig for them.

*Corrections: Through the years, changes occasionally take place in the Linnaean nomenclature (more popularly known as “Latin names”) for various organisms—usually in the species (the second word) rather than in the genus (the first word). Whether this is the case with several of the plant species Ms. Krueger Curtis painted, or whether she made errors in labeling a few of her watercolor images, it is impossible to say for sure, however several corrections are necessary. Her use of Verbena scabra with her illustration of Vervain is slightly misleading. The proper nomenclature for the specimen depicted is Verbena hastata, var. scabra, commonly referred to as sandpaper vervain.The label Galium boreale, used to identify stiff marsh bedstraw (Galium tinctorium), actually identifies northern bedstraw. The correct nomenclature for prairie smoke is Geum triflorum. Geum canadense is the nomenclature for another flowering plant, white avens.