Dartanyan Brown and the members of the Drake University Jazz Band in 1974. He is seated front row center with his bass. Future wife Marcia Miget is at the end of the second row, on the right, holding her saxophone and flute.

When I got back to Des Moines in the Fall of 1974, I saw that many things had changed. I returned to Drake University, where I found the jazz band energized by several new young members who had a lot of enthusiasm. Robert Weast, band director and now a good friend, introduced me to a freshman woodwind player named Marcia Miget early in the 1974-75 academic year. Marcia, from Perryville, Missouri, immediately charmed anyone who heard her play either woodwinds or keyboard. We shared an instinctive musical communication, and before long we were playing together. Marcia played in an off-campus band called the Midwest Express. Beside her, the group included Drake student and keyboardist Bobby Parker, Des Moines resident musicians Danny Nicholson (guitar) Terry Condor (bass) John Grgurich (drums) and blues shouter Big Mike Edwards, who rounded out the group. Big Mike brought an intense vocal energy which really made the band a popular force in town. It was great to jam with kick-ass players on the local scene again. No big egos, no high stakes; just play your ass off and have fun.

I’d really wanted to concentrate on finishing up my degree and even, possibly, return to reporting. I’d felt like I’d “been there, done that” as far as music was concerned and I certainly didn’t anticipate having a band as fun or successful as Chase again soon—if ever.

Midwest Express playing a gig in 1976. From far left, Marcia Miget is on saxophone, with Danny Nicholson behind her on guitar and Big Mike Edwards next to her at the mic. Dartanyan Brown (against the back wall) is on bass, John Grguric is on drums, and Bobby Parker is seated at the keyboard

After a few months at the Des Moines Register, though, it was clear that the old days were long since gone. Technology had completely transformed the production of the paper and ownership was in transition. Frank Eyerly, who had been the paper’s managing editor during my previous tenure there, was gone. The newspaper’s editor was Michael Gartner, a local boy who had gotten his start at the Register as a janitor in his teens, and had then gone on to editorial posts at the Wall Street Journal, USA Today and the Louisville Courier-Journal before bringing his business acumen back to the Register’s newsroom. His business-friendly approach to journalism seemed at odds with the investigative roots I had sprouted while I was there from 1967 to ’70. Indeed, Gartner would eventually leave the newspaper business entirely, finishing his career as NBC News’s president.

The assignments I was given at the Register were few and far between, which also sent a message about what I could expect to achieve in a career there after graduation. It wasn’t especially encouraging.

Where I had once hoped for a career in journalism and writing, I now realized that even if I hadn’t messed up my own chances at a career, the business of journalism was already showing signs of serious decline. One former Register editor termed it “our dark period.”

During those dark days of 1975, the paper “All Iowa Depends On” began a three-decade slide into what has become the paper “all Iowa descends upon” with frustration at the paucity of its coverage. The purchase of the organization in 1985 by Al Neuharth and the Gannett Corporation only seemed to accelerate the decline. It seems incredible that the flagship newspaper from a major agricultural state has no Washington bureau. But, so it is.

The year I spent as an “intern” at the Des Moines Register upon my return to Drake University was enough for me to know something had really changed. I didn’t realize it in 1975, but technological developments that would disrupt our entire culture were well under way in the news business and the music business. Typesetting, formerly done by well-paid union labor, was now being performed not in a hot, dangerous environment, but in a well-appointed office.

Music—formerly composed or played almost exclusively by human beings who played real instruments—was now increasingly composed and programmed by a new cadre of musicians who could control computer-driven instruments to replace the humans formerly employed as studio musicians.

I might have been happy working at the Register again if it had been like it was in 1967, but those days were gone and 1976 was right up ahead.

Crazy Fun

The Midwest Express band was turning out to be crazy fun. With each new rehearsal or show, I lost that jaded feeling I had gotten from life on the road, and frankly the musicians on the local scene were pretty awesome.

Each member of the band offered something very special. Danny Nicholson could soar on guitar, while pianist and electronic music enthusiast Bobby Parker was the brain of the band. Classically trained and soulful as a plate of fried catfish and black-eyed peas, Bobby was de facto arranger for the Midwest Express. Marcia, whose own family performed as a 4-part harmony vocal group, also brought huge arranging talent to the band.

Soon Marcia’s and my musical friendship blossomed into something much more significant. We were married in November 1976. With the band and our families in attendance, the reception/jam session went on for hours.

With the birth of our son Jaimeo in January 1978, I reformed the band, expanding the lineup to include keyboardists Lynn Willard and Sam Salamone, guitarist Rod Chaffee and Latin percussion master Bobby Aguinga.

In 1979, we produced a very well-regarded boutique-label LP titled Influences. Co-produced by the band and local radio legend Ron Sorenson, the collection of original Jazz, funk, Latin-jazz and Americana, remains a sought-after collectors’ item in Europe as well as the U.S.

It was at this time that Marcia and I began trying to pull all the threads of our creative and academic lives together. Jazz education became the focal point for both of us.

Let me briefly describe how I decided on a new direction:

During my time with Chase, I would sometimes tag along while Bill Chase did “clinics.” Clinics were master-class sessions where he would discuss his personal journey as a musician and demonstrate examples of the technical issues inherent in playing brass instruments.

Hearing Bill describe how musicians worked together reminded me of watching my father practice with other musicians in our home when I was a kid. It struck me how different jazz education was from the relatively sterile music environment I had experienced in high school. I realized that the oral tradition—the powerful, but simple method of communicating across generations—was going to be key in my efforts to create a fun and challenging Jazz education program.

I started submitting grant applications to the Iowa Arts Council in 1976 for funding to offer a program of music history, performance and education from the perspective of an African American Jazz musician. These applications were unsuccessful for several years, until 1979, when Marcia and I were asked by Iowa Arts Council director Nan Stillians to meet with A.B. Spellman, a site-director for The National Endowment for the Arts who was visiting from Washington D.C.

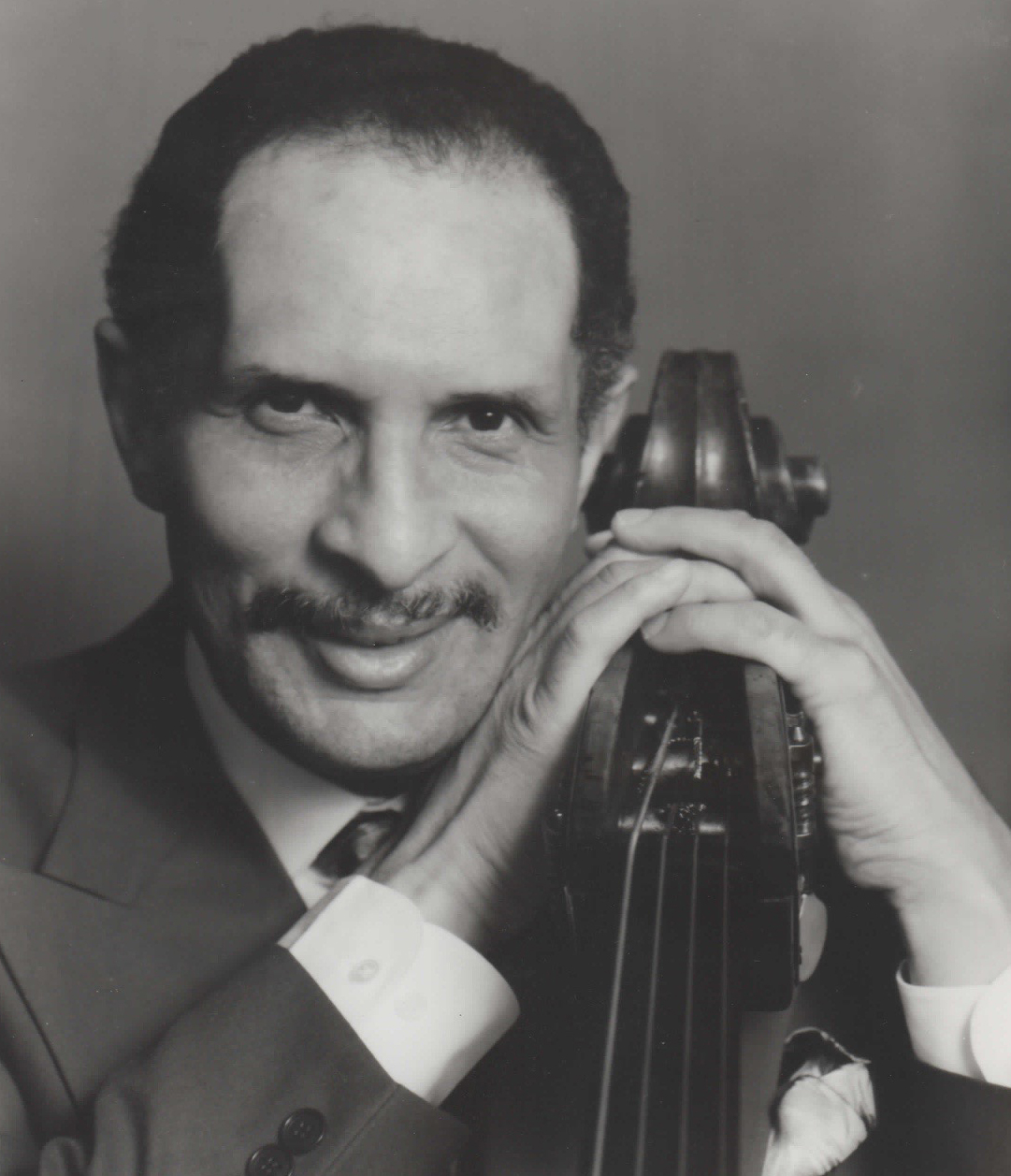

Dr. Larry Ridley, the Rutgers University professor who founded the Jazz Artists in the Schools Program

Mr. Spellman, impressed with both our music and our approach to education, introduced us to Dr. Larry Ridley, a Rutgers University professor who was himself an internationally acclaimed jazz bassist. Ridley formed the Jazz Artists-in-the-Schools (JAIS) program, which was sponsored and endorsed by The National Endowment for the Arts.

Marcia and I were selected to participate in the founding conception and implementation sessions of the JAIS. They were held at Duke University in North Carolina, and the original crew of artists and educators included the late Dr. David Baker from Indiana University, teacher Jamey Abersold, pianist Kenny Barron, clarinetist, the late Alvin Batiste, guitarist Ted Dunbar, trumpeter Bill Fielder, composer Frank Foster, trumpeter Pat Harbison, Thelonius Monk’s alto saxophone soloist Charlie Rouse, and drummer Art Taylor. My old Chicago friend from five years previous, Arnie Lawrence, was on the original crew, too. From our initial sessions in 1979 at Duke University, JAIS artists were dedicated to delivering a more culturally balanced and rigorous approach to teaching the fundamentals of jazz improvisation within the k-12 music education curriculum. Conveying what that meant in practice requires a little explanation.

Jazz music, like most organic African-American forms of expression, had to run the gauntlet of acceptance into the American experience. Coming from the lowest rungs of the social and political hierarchy, African-Americans were caught up in a dichotomy: discriminated against as an ethnic group, some were lionized nonetheless as creators, innovators and heralds of anew American voice in the Arts.

America, naturally, looked at things through the lens of its European cultural roots. The wildcard, though, was the advent of slavery and the introduction, willing or not, of humans from the African diaspora into America’s economic and cultural life. The integration of European and African cultural expression in America produced a new consciousness which expressed itself in music, visual art, theater, dance, and many other fields of endeavor.

Jazz began stretching music in two directions from the center— ever more harmonically intriguing while at the same time exhibiting a rhythmically-seductive energy that would eventually set the world jitterbugging, bebopping and scat singin’. While it may have been recognized as a new popular music, though, it was, until the 1980s, viewed as totally unworthy of “legitimate” study by most of collegiate music education.

I remember stories of students in the early 70s in Drake University’s conservatory-style music program being in big trouble if they were “caught playing jazz” in the practice rooms. This attitude, completely understandable from the perspective of the European-Classical ethic, represented a reluctance, or in some cases a refusal, to acknowledge the dawn of the new, highly technical form of music which now required the player to incorporate her ideas in real-time concerning note choice, dynamics, and literally dozens of other decisions directly into the performance, instead of just interpreting the notes as written. Music educators’ heretofore-condescending attitude toward jazz music began to fray, though, as academics began looking under the hood at the innovations that Armstrong, Ellington, Parker, and Basie were exhibiting in their compositions and the performances that were taking place nightly on stages across the world.

Some African American jazz artists in the 70s referred to their oeuvre as Black Classical Music, attempting to wrest a measure of respect from the conservatory that only grudgingly admitted its legitimacy. An important corollary of the civil rights movement was its drive to define the Black experience outside of the usual American (read: White) perspective of things. To sum it up in a phrase: we now proclaimed that Black music was Beautiful.

With that being said, jazz—while originating in the African American community—was from its inception a multi-racial and multi-ethnic experience. Classical music, on the other hand, was almost conducted as a high priesthood where African American musicians, while talented enough, often found themselves on the outside for “other reasons.”

Of course, there were notable exceptions to this condition. Iowa’s own Simon Estes became an international star as the pre-eminent African-American bass-baritone operatic singer of his time. In fact, Simon, who performed for presidents and popes, is credited as one of the first of his generation of black artists that opened the way for others to contribute also. Chicago’s Richard Davis, the esteemed classical and jazz bassist (and one of my early teachers) developed a resumé of accomplishment in the worlds of live jazz and classical performance, studio recordings and later education as a professor of Jazz and African American studies at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Richard performed under the baton of Leopold Stokowski with the Chicago Symphony during the 1960s, while at the same time recording and performing as one of the premier talents in jazz music.

As jazz music gained in popularity in academia, uninformed, inexperienced teachers began mis-applying the standards of their classical or marching band training to the teaching of jazz music, which often fell short of giving students the true essence of the improvisation experience.

Members of the Jazz Artists in the schools program, standing in the back row, from left ot right, they are Kenny Barron, Charlie Rouse, Horace Arnold and Willie Thomas; seated are (from left to right) Dartanyan Brown, Marcia Miget, Jim Fielder and Larry Ridley

This refusal (or inability) to recognize creative music rooted in African American culture as legitimate was cultural chauvinism, and a negative force. It was, of course, the legacy of an America where renowned Black artists could command the stage in performance, but still had to stay in dive hotels or eat in back rooms because of America’s deeply ingrained and unrestrained white supremacist tendencies in those years.

These perspectives might have continued to be seen as valid, if the marching band/symphonic band experience had continued to predominate. In the new jazz era, however, the thorough-composed orchestra was being replaced by small free-wheeling bands that used song structure. Rather than allowing this to be a strait jacket, artists in these groups used these songs as wings that enabled them to tell their own stories through the chord changes.

Indiana University professor Dr. David Baker developed a method of breaking out jazz’s harmonic, rhythmic and melodic developments into units for study. His groundbreaking work greatly enabled jazz education’s acceptance into the academic world. In the early 1970s, school jazz programs were a rarity, but by the mid-1980s, jazz programs were obligatory for any school professing to offer a complete music curriculum.

…Now, about the subject of rigor. Developing the idea of chord/scale relationships (as in: if you hear that chord, play this scale) was a pretty important concept for study. The Great American Songbook (popular song standards of the 1920-1950s) provided the material to which those chord/scale relationship studies would apply.

Rigor, in these terms, meant a number of things. It meant learning to play your ideas in any of the 12 possible key signatures. It meant learning to play your ideas accurately at tempos anywhere from 50 to 150 beats per minute. It meant learning to play your ideas in 4/4, 3/4, or even 7/4 time signatures, spending at least six hours a day practicing your instrument, going to jam sessions with the goal of having the best ideas, and memorizing as many songs as you possibly could.

The intervening years have seen a blossoming of jazz education worldwide. It flourishes because it is difficult and demanding, and it continues to attract lifelong learners because of its dual role as a balm for the spirit and a spur for the mind.

In maintaining that Oral Tradition, I pass what I learned from Dr. Larry Ridley, Speck Redd, Bob Weast, Frank Foster and Dr. David Baker on to new generation of students and musical seekers. Having made that explanation, I can return to my experience with the Jazz Artists-in-the-Schools (JAIS) program. Beginning with workshops in the Des Moines Public Schools, our program blossomed to include residencies in Montana, Arizona, North Carolina, Louisiana and Wisconsin. We still hear from students today that we mentored as middle or high school students during that period from 1979 through 1985.

Inspired by artists like John Cage and interdisciplinary projects like the Black Mountain College, my first conceptual objective was to highlight music’s relationship to history, mathematics, creative writing, and, of course, science. I focused on two prime elements for development: education and learning. In my limited view, education is the yin to the yang of learning. An inefficient education system may not necessarily foster learning in the minds of the students subjected to it.

Learning is what an individual must do in order to gain mastery over a situation. It is most effectively fostered by two elements: survival and curiosity. Put another way, curiosity is the itch that learning must scratch.

When education enables playful pursuit of one’s curiosity, it opens the door to lifelong learning. Education fails when insufficient resources and inspiration leave curiosity with no positive outlet. We in education do our students and our communities a disservice when we forget that students themselves are ultimately in charge of their own learning process. If they are allowed to make decisions and experience the results of those decisions sooner rather than later, they do it just fine.

The concept of freedom-within-structure highlights a tension inherent in the process of improvisation. In designing our curriculum to aid students and teachers to examine the nature of that tension, I hoped to encourage discovery of a collaborative framework that might enable teaching artists and their students to explore jazz improvisation, as well as expanding the concept to include study of the relationships between cultures, between generations, or between value systems. Call it my attempt to better illustrate the more durable and the timeless elements that sustain us.

The 1984 election of Ronald Reagan meant a change of budget priorities for the federal government. Our Artist-In-Schools Program was scaled back considerably, and by the next year Marcia and I decided to return to Des Moines with our now-school-age son Jaimeo and three-year-old daughter Marisha.

I bought my first Apple Macintosh computer in 1984 at Computer Emporium, a Des Moines company co-owned by Richard Skeie, Donald Brown and John Kirk. The company sold computers, but more importantly, it wrote software for them too, an enterprise which eventually drove the company’s transformation from the Computer Emporium computer store into CE Software, a software design company that would become a major player in the Mac software universe of 1984-94.

Don Brown, a Drake actuarial grad, was the company’s lead programmer. Don wrote Sidekick, the first successful Personal Information Management utility for the Mac platform. That success led to QuickMail, an email application that propelled the tiny West Des Moines company into the elite of early Mac software houses.

Richard, Don and I were all Drake University grads, and I had met them because they were fans of my music. Later, I would hang around the Computer Emporium geeking out on music and computer possibilities.

One of our ideas (remember, this was 1984) was to create software to record musical sounds in the same manner you ‘recorded’ words by typing in a word processor. Text and sounds, after all, were just ‘data,’ and the computer could be programmed to handle data, no matter the type.

In 1986, I was approached about starting a new recording studio in Des Moines. Entrepreneurs Roger Hughes, Dr. Jim Skinner, and Chief Engineer Pat McManus were all interested in building a new type of studio using computers to augment traditional recording methods.

I already had experience with digital audio and the Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI), a protocol that enabled communication between computers and electronic musical instruments, so in mid-1986 we opened Audio Art Recording Studios just over the 9th St. viaduct south of Downtown.

It was an immediate success. Songwriters and small producers who needed high-quality work with faster turnaround than they could get at the bigger, busier studio in town flocked to us. We used cutting-edge digital audio tools for traditional band recording, songwriter demos and corporate video projects, and before long our work was being used in local advertising on radio and television stations in our market. Technology, art, and now commerce were all integrating nicely.

The California Years

I was working at Audio Art Studio in early 1987 when I got a call from 2,000 miles to the west. Teja Bell, one of my closest friends and fellow Des Moines native, was on the phone asking me whether I’d consider taking a trip to Northern California. Teja and I had been friends since late middle school. He had been one of the first of us to actually pick up a guitar and learn to play Beatles songs. This was 1964-68. As the civil rights and anti-war movements spun up, we played folk songs from The New Christy Minstrels and protest songs by Pete Seeger in the high school’s student center.

Teja was now making digital music history, writing, performing and producing a critically acclaimed (and hot-selling) album entitled Dolphin Smiles. It was noted as one of the best of the new genre dubbed New Age, which integrated acoustic music from around the world with synthesized tones designed to invoke an ambience conducive to meditation.

I never would have dreamed that two decades [1967-1987] after high school my friend would call me from San Anselmo, California, to cajole me into considering a trip to San Francisco for the purpose of recording, performing and basking in New Age wonderful-ness.

I flew out in October 1987 to check out the scene, arriving late in the evening on a flight from Minneapolis to SFO. On arrival, Teja and audio engineer Daniel Ryman picked me up at the airport. We glided north on the 280 Freeway, heading toward the Golden Gate Bridge and Marin County. The full moon was rising over the San Francisco Bay to our East as we crossed the Bridge I’d only ever seen before on TV.

When I arrived in San Anselmo, my senses became aware of two things: a steady, gentle rain on my face and the aromatic fragrance of wet redwood bark and jasmine. These two sensory experiences were my cosmic baptism into life in Marin County, the New Age capital of the world at that time, where hippies with computers and guitars were dedicated to saving the world with sound.

Ray Lynch (the creator of Deep Breakfast, which in 1989 peaked at Number Two on Billboard’s “Top New Age Albums” chart) was there. The pioneering synthesizer programmer Suzanne Ciani was also in Marin, after moving from NYC. Don Buchla was building synthesizers in the East Bay. Dr. John Chowning, a Stanford University-based researcher, invented Frequency Modulation (FM) synthesis which combined up to six digital oscillators to either emulate existing instruments or create new, unique sounds. David Wessel (who has since died) was running the Center For New Music and Technology (CNMAT) at the University of California, Berkeley, and inventing new input devices for the music of the future.

While all that was fun, I was soon driven by the necessity to look beyond music performance to earn enough to keep body, soul and hungry children together.

The Mac Garden

Thanks to my Iowa tech background, I was prepared to grab a job at The Mac Garden, a computer store located a few blocks from our house in San Rafael. It was one of the first Mac-only retail stores anywhere, and its owner, Chet Zdrowski, was looking for a new sales/ tech support person. I was hired, and now I was holding a mouse instead of a guitar. The mouse was connected to the Mac, which in turn connected me to an insane collection of artists, musicians, programmers, visionaries, charlatans, seers and other digital New Age hippies who gathered in the San Francisco Bay Area between 1989 and 1991.

The staff at the Mac Garden was a crazy crew of first-generation Mac retail sales zealots. To us, selling Mac stuff wasn’t selling; it was enabling people to follow their passions and dreams. Want to write a book? Get a Mac and a Laser printer. Want to make a movie? Get a Mac and a camera. Want to identify atomic elements? Get a Mac and a scope.

In San Rafael, George Lucas’s pioneering special effects studio, Industrial Light and Magic, (ILM) was where work was conducted on little projects like Star Wars and Terminator 2. In 1989, George’s guys, including John Knoll, were coming into the Mac Garden, demoing the beta version of their custom digital image manipulation software that would later be sold to Adobe Inc. and released as Photoshop!

Stewart Brand, founder of The Whole Earth Catalog, and Howard Rheingold, co-founder with Stewart Brand of The WELL (Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link) both came in. Ted Nelson, the man who coined the term “hypertext,” became a good friend. I was also thrilled to work as a computer consultant for the late jazz drummer and composer Tony Williams, who lived in San Anselmo.

While the experience I was garnering at The Mac Garden was important, it was Richard Skeie, owner of Computer Emporium back in Des Moines, who set me on quite another path into Silicon Valley. In January 1990, I was in San Francisco, attending the MacWorld Expo—what used to be Apple’s annual haj of the Mac faithful. While roaming the aisles, I encountered Richard in the CE Software booth. Unbelievably, after a handshake and a howdy, he hired me on the spot to be part of his company’s West Coast marketing team.

I traveled the Western region with marketing director Brad Sharek, evangelizing CE products to eager digital disciples. Presenting at Lawrence Livermore Labs in Mountain View, California, or in front of the Portland (Oregon) Macintosh User Group (PMUG) was a spectacular experience.

Unfortunately, though, the advent of the Internet—great for Apple and Microsoft—by 1993 rang the death knell for little companies like CE Software. The company’s business model was eviscerated when Apple made the decision to rely less on outside developers like CE, instead writing its own business application software. Since Apple is valued today at a trillion dollars (give or take), I’d say they had the right idea!

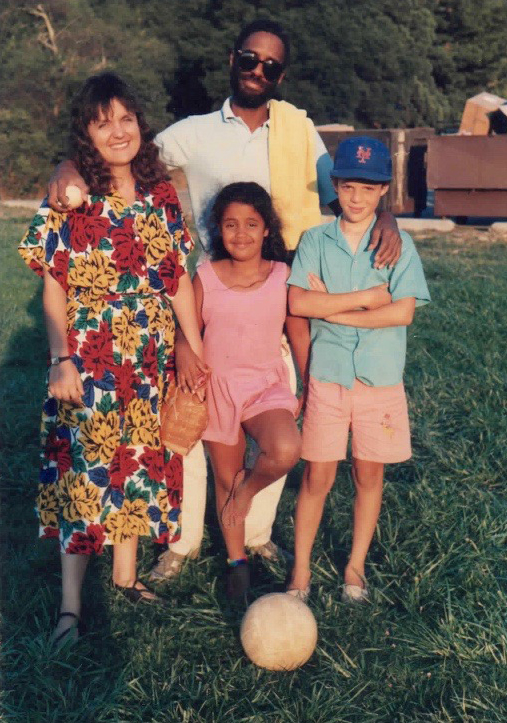

Dartanyan and family in Berkeley

Dartanyan Brown demonstrating CE software for jazz great Herbie Hancock at the MacWorld Expo, Hancock was one of the earliest musicians to explore the intersection of jazz and technology

While still at CE in 1991, I met Henry Norr, the news editor for MacWEEK a Ziff-Davis owned trade publication that functioned almost like an early WikiLeaks, providing hot tips, product news, and sensitive information poached from inside Apple which had some bearing on the nascent Macintosh computer market. Henry hired me away from CE, and the investigative/writing skills I had honed during my time at the Register now served me well during a 17-month assignment as a staff writer and reporter.

One highlight of the job was getting to interview the late Steve Jobs while he was in exile from Apple in 1992 at NeXT Computing. He didn’t allow me very much time, but as we shared a mordant chuckle regarding Apple, led by then—CEO Michael Spindler, I had a feeling he was plotting his comeback to Apple, and I was right.

Back into the Classroom

This was now 1993-94, and as our son Jaimeo was heading into high school, my marriage to Marcia was dissolving. Thankfully, we maintained our relationship as committed co-parents, but I felt a strong need to spend much more time with both our children. My work at that time included long periods away on business which—while good for my career—was not so good for the relationship I needed to maintain with my children at a critical period in their lives.

That was when I left MacWEEK and signed on as a computer lab director at San Rafael High School, where my son was a freshman. This was the dawn of networked-computer labs in education. While I wasn’t a certified teacher, my experiences as a tech-savvy artist proved to be pretty valuable in that environment. Offering new perspectives on problem-solving is the heart of education. I saw time and time again that improvisation and the sense of adventure inherent in playing jazz were also vital ingredients for a fulfilling educational experience.

In his 8th grade year at Davidson Middle School, Jaimeo won his division of the Marin County Science Fair. Our computer could act as an oscilloscope, so we decided to record and display the waveforms of equivalent acoustic and digitized electronic instruments. For example, Jaimeo sampled his mother’s saxophone and compared it to a synthesized woodwind instrument. He did the same with my acoustic bass violin, contrasting it to an electronic version.

The project was relatively simple but, of course, not many people were equipped to use computers in such a way at that time, so he won on originality and for the cool data the project produced.

It was confirmation that improvisation, analogy, and play are all present when you have a well-thought-out curriculum, particularly in grades 6-12.

In 1996, our daughter Marisha was accepted into the freshman class at The Branson School, a 320-student private high school in Ross, California, which exemplified the rare but critical mix of qualities outlined above.

Upon Marisha’s acceptance, I was invited to apply for the recently opened position of Director of Technology. The Branson School (Julia Child’s alma mater, by the way) was one of the first high schools in the nation to have a website. Branson.org was created by the legendary, (at least in the Bay Area tech world) Miko Matsumura. Upon leaving Branson in 1996 to become a key member of the team at Sun Microsystems that was charged with introducing its new Java computer language to the world, Miko handed me the controls of the school’s HP9000 mini-computer.

‘Seeing’ music thanks to the computer helped Dartanyan Brown’s son Jaimeo to win honors at the science fair

The next four years were an incredible experience for us at TBS. The fact that Marisha’s academic performance earned her distinction as valedictorian of her graduation class (1999) would have been no surprise, but a source of no little pride, for her ancestors—my father, Ellsworth T. Brown, and my mother, Mary Alice Thompson. My mother learned her lessons in mental preparation from my grandmother, Lettie Thompson of Buxton, Iowa, who received these values from Blanche and Ross Johnson, out of Charlottesville, Virginia. Lettie believed the way to success was through “hard work; hard work and plenty of it.” Her ethos was what enabled my daughter to lead a competitive group of 319 university-bound peers. If Lettie had been there for Marisha’s commencement, she would have said: “See, I told you.”

In 2003, Bob Schleeter, a Des Moines native and a fine guitarist, invited me to join the fine arts faculty at Marin Academy in San Rafael. Bob and I spent the next 10 years designing a performance-oriented music program that made it fun to learn the roots of American music, earning it a reputation as one of the most challenging programs in Northern California. I worked at Marin Academy until I left California to return to Iowa, in 2016.

Becoming a teaching artist in California had reconnected me to my beginnings as a jazz educator back in the 70s. My parents and my Grandmother Lettie had taught me that education was one of the things that could free you, but only if you did the hard work it took to put what you learned into practice. My Integrated Life would not have taken the trajectory it did if I hadn’t been exposed early in life to a variety of experiences, and if my folks hadn’t thought deeply about what kind of life I should be prepared for.

Changing careers in 1993 was a critically important thing to do when my son and daughter needed my physical presence in addition to my emotional support. I was grateful I had the skill-set and flexibility to make it work. Once I became a teacher, though, I realized that many other kids needed the same level of support. That realization drives me today as I continue being there for students who may need just one more encouragement (or admonishment) to keep them on a path to attaining the goals they set for themselves.

by Jeffrey Gilbert, at the Urban Education Network (UEN) of Iowa Legislative luncheon on November 18, 2015. Chart supplied by [Iowa School Finance Information Services](https://www.iowaschoolfinance.com/)](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2020-spring/grinnell_28539_OBJ.jpg)

Chart from ‘A little about the Iowa Economy and State Budget’ a presentation by Jeffrey Gilbert, at the Urban Education Network (UEN) of Iowa Legislative luncheon on November 18, 2015. Chart supplied by Iowa School Finance Information Services

What Made My Integrated Life Possible?

I was able to surmount the challenges and take advantage of the opportunities My Integrated Life presented to me because I was well-prepared. Between the years 1949-80, the Iowa legislature provided adequate funding for the public-school system, making Iowa a national model of how education funding ought to be done. As a result, during my childhood and early life from 1955-67 I benefitted from a solid, universally accepted school curriculum and well-respected (i.e., well-paid) teachers who were backed up by an administration adept at supporting, not obstructing them. (My parents also made a pact with my teachers to keep close watch on me. No goofing off for me.)

My family’s experiences since arriving in Iowa from Charlottesville, Virginia, in 1895 constitute the other crucial part of the platform on which I could build. I saw how these experiences manifested themselves in work, in religion, in education, in art, and in love. To the family elders who worked themselves half to death to provide for us, I give ultimate respect and dedicate this writing to their enduring spirit.

When I left Iowa in 1987, as I remember, our public school system from kindergarten to university was ranked very near the pinnacle of public education in the U.S. I returned to find that this is no longer the case, and that politicians—the caretakers of our public education dollars—seem to be at war with the very institutions they’re tasked with protecting.

Since returning to Iowa in 2007, I have witnessed directly what we lose here when bright kids aren’t provided with the parental guidance or community support they need to follow their dreams. In my experience, the most important aspect of learning is exposure—to new ideas, new cultures, new music! The sooner a student learns to acknowledge other cultures, the sooner that student will learn to incorporate the best of what those cultures offer into a personal toolkit for success. If we deny students those opportunities, we waste their potential, and our communities are the poorer for it.

In Iowa in 2019, public school teachers, healthcare workers and public union workers have lost union bargaining rights and respect. They endure attacks by those whose only purpose seems to be sowing division and reaping political gain at the expense of our most vulnerable citizens. Sane civic governance seems to be in freefall, with no one currently able to arrest this sad trend.

All of us—parents, school teachers, students, school administrators, community partners and supporters—share an interest in working more effectively together for the good of the entire system. Convincing Iowans to change legislative direction regarding public education will be hard, and there are challenges, but the landscape is far from bleak. Thanks to progressive grassroots organizations, including Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement, (Iowa CCI) I’ve witnessed rural and urban communities finding their voice andbuilding their power to effect change on environmental justice, employment, healthcare, civil and human rights issues.

One such example took place in Mason City, Iowa a few years ago (covered. in Rootstalk in Volume III, Issue 1, Fall 2016) In an all-too-familiar story for Iowans, Prestage Farms, a major corporate food processor based in Clinton, North Carolina, came to Mason City offering to build a new plant and create nearly 1,800 new jobs. Behind closed doors, the city council and state leaders brokered a sweetheart deal worth $26 million in tax abatement and other giveaways of public resources.

Unveiled in a city council meeting with little public scrutiny beforehand, the deal passed on an initial vote of 6-0.

Iowa CCI opposed the deal, partnering with community members around the guiding concept that, when there is talk about using public money, that money should be used for the public, not to satisfy corporate greed. Over a six-week campaign Iowa CCI began educating rural and urban citizens to the massive health, education, environmental and labor issues they felt were sure to upset the balance the community was seeking. The group highlighted labor, environmental and human rights issues, and in the next city council meeting enough councilmembers changed their vote to earn a 3-3 deadlock, essentially a rejection of the corporation’s overtures.

Work like this is not easy; in fact, it is hard, hard work to organize, educate, motivate and then activate a community. I have written here extensively about the problems, but I rest easier knowing that a well-grounded progressive organization like Iowa CCI continues to provide vision and energy to counterbalance forces that would exploit our communities.

In public education, administrators, classroom teachers, resource workers, coaches and staff perform unseen miracles with our youth. The courage demonstrated by our immigrant youth—stalwart while being persecuted—reminds me of the values my ancestors passed on to me. My efforts for the last decade here in Iowa have focused on directly engaging students and teachers to create interdisciplinary arts experiences for every middle and high school student we can. In partnering with the Des Moines Public Schools, these projects, often involving student-generated original music and sound elements, have relevance to—and can thus be integrated with—their science, mathematics, history and writing classes. Using music as the pathway to learning has proven to be a reliable way to communicate with students who might otherwise fail to engage. I carry this message to school boards, educational policymakers, parents, PTO groups, legislators or anyone else. We often need to restate basic foundations in reminding ourselves of our mission as a community in support of public education.

In closing this story, I return again in thought to my parents, who literally fought for me to have opportunities. Teachers and coaches at school were pivotal, but in the absence of close parental attention, the best efforts of everyone else may be undermined. Whether we’re talking about affluent private schools or urban public schools, one thing is clear to me after 24 years of involvement in education: the more cooperation between the parents and their children’s schools, the higher the level of satisfaction for everyone associated with the school. Everyone from students through the principal can work together to improve the atmosphere for learning. A renewed sense of mission involving all of education’s stakeholders could result in an “idea hive” effective enough to influence legislative behavior on issues critical to our public education system.

Yes, we have differences between us, but young people seem to understand that our differences are all wrapped up in a common package called humanity.

Humanity is the trait we all share. Taking that fact to heart, I believe, is the first step toward cultivating communities that are wiser, more progressive, and less hypocritical. Those who have had a life like mine—in which they witnessed our culture’s transformation and the emergence of a more equitable, inclusive world—are now tasked with keeping the light on for others to follow in the future.

We’re Midwesterners. We plant things. My mission (and I have chosen to accept it) is to plant seeds of success today knowing that in the not-too-distant future, there will be a harvest of community, creativity and achievement as our young people mature. I was well-prepared by my Iowa teachers, community leaders and my family. I can do no less than continue to pass that legacy on to new generations of young people who will join us in restoring the bonds of trust connecting our region’s progressive past to a future that features even stronger communities.

Dartanyan Brown’s parents, Ellsworth T. and Mary Alice Brown (in the middle of the picture), on their wedding day in Los Angeles

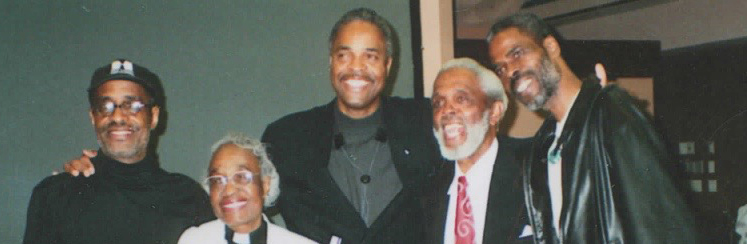

The last time the family Mary and Ellsworth created was together, in Des Moines, 2010, when Ellsworth was inducted into the Iowa Jazz Hall of Fame. From left to right, Dartanyan Brown, Rev. Mary Alice Brown, Don C. Brown, Ellsworth T. Brown and Kevan L. Brown