The storm on August 10 began the way so many others do in the Midwest: a darkening sky, pulled like a curtain across the western prospect, the light changing from brassy-brightness to gray. But then things went green, as if we had been plunged suddenly beneath the surface of an algae-choked farm pond. I was standing in the front doorway of my 1880s house, watching it unfold.

Leaves and twigs began to fall from the trees in my yard. Nothing unusual about that. One of the rituals of summer here is picking up sticks after a storm. But in the few minutes I stood there watching, the wind steadily grew. Then the wall hit.

It was a derecho—a fast-moving, straight-line storm system that can travel hundreds of miles on a vast front. News accounts later said that the wind-gusts went as high as 140 mph, making the storm like an inland category 4 hurricane. The rain blew in sideways; first branches, then limbs began to fall, and then the top of one of my mature maples came down with a crash. I decided it was a bad idea to keep watching, and retreated further into the house. The house’s frame reverberated as a venerable hackberry—three feet in diameter—gave up the ghost and struck a glancing blow to the northwest corner of my roof. Above the howling of the wind around my house’s eaves I could hear more trees toppling. I looked out another window and saw a terrified German shepherd come pelting at full speed across my back yard, looking in vain for shelter.

It was over in about 20 minutes, and when calm was at last restored, my neighbors and I emerged into a changed world.

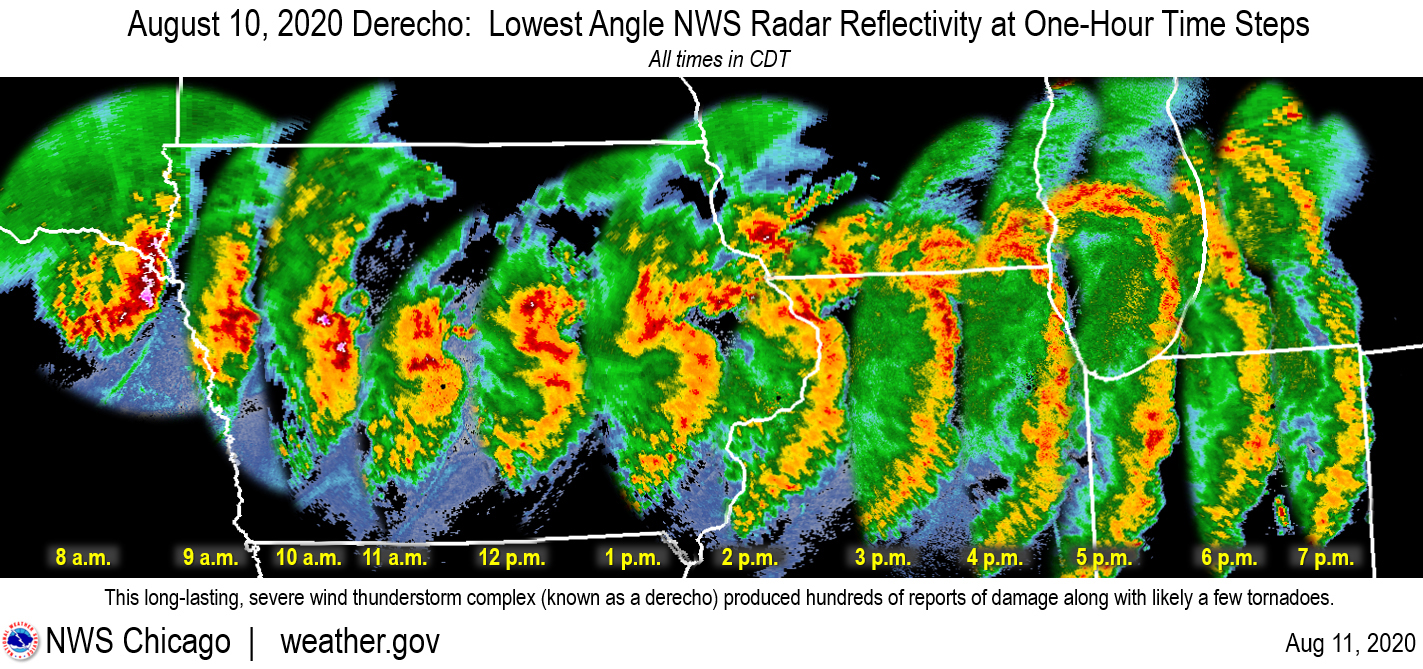

Radar image of the August 10 derecho by the National Weather Service

I couldn’t get out my front door at first; my porch was completely blocked by the crowns of the trees that had been wrenched off and flung there by the wind’s power. Many cars parked in the streets were damaged; one of my next-door neighbor’s vehicles had been smashed like a stepped-on tin can.

My neighbors and I called out to each other, asking whether anyone was hurt. Miraculously, no one was. The whole town had lost power in the storm’s first few minutes, and most of us wouldn’t get it back for 10 days. We had no phones, no internet, no air conditioning. Our refrigerators and freezers began to warm, and all the food they contained to spoil. It was like we’d been blown back into the mid-19th century.

We would learn later that our experience was duplicated across the country’s midsection. The derecho traveled at freeway speeds for 770 miles, from South Dakota to Ohio and lower Michigan, over a span of 14 hours. Whole towns were blasted. The mayor of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, estimated that there wasn’t a square mile of his city that hadn’t sustained damage. Billions of dollars-worth of corn and soybeans were flattened in the fields.

Devastation, by any definition. And yet, in short order, we began to pull together.

The day after the storm, Megan, my coworker at Grinnell College, showed up with her neighbor John and a chainsaw. My teenaged daughter Claire pitched in too, and the four of us spent a busy morning cutting and stacking debris. Then it was my turn to help them. It was a scene being repeated up and down the street, and our town’s soundtrack for the next week was the steady growl of chainsaws during the day and the thump of gasoline-powered generators at night. Line crews showed up from as far away as Wisconsin to help get the town wired back together again. One crew from Quebec even took part.

Todd and Shannon, neighbors a few blocks away, have a house with a big front porch and a capacious gas grille, and it became the unofficial evening gathering spot for the cleanup crews that patrolled the neighborhood’s back-alleys and front yards. Everyone was emptying their freezers, using Todd and Shannon’s grill to cook whatever they had before it spoiled, and adding it to the community potluck. My garden came through in remarkably good shape, so I was able to throw together a few massive salads as my contribution, along with a dozen or so pork chops that would otherwise have gone to waste. Everyone in Todd’s and Shannon’s yard was mindful of the pandemic, wearing masks and sitting in lawn chairs six feet apart, resting from the day’s labors, chatting, watching as the kids chased each other in the waning light of evening.

It wasn’t long before someone stated the obvious—that this was how things used to be, before our lives came to be dominated by screens, before COVID hit and virtual work and video meetings—once the realm of science fiction—became our daily reality. Before we plunged down the rabbit hole of isolation.

One night as we all sat with our now-empty dinner plates in our laps, Todd said: “We should keep doing this!” At the time, we all agreed, and for a few nights, we did. I wish I could say we continued beyond the end of our cleanup operation, but when the lights came on again, when the cell-towers went back into service and the fiber optic cables were restored, when the streets began to be cleared of their heaps of debris so traffic could move unimpeded, we went back to our dens and living rooms, and the whine of our central air units replaced the steady thump-thump-thump of the generators. Our society fragmented once again, our gatherings shrinking from neighborhood-sized to the dimensions of our living rooms, our couches. The many dwindled to a few, or even to just one.

We’ve had what has arguably been one of the worst years on record: a disastrous season of weather-events like ours, driven by climate change; political tumult of an unprecedented rancor; the flouting of many of the norms of decency, plain-dealing and probity which we have previously taken for granted as features of our democracy. Civil unrest has convulsed our cities, highlighting the deep divisions and inequities to which our society has turned a blind eye for too long. And then, of course, there is the election, which has been like none in modern memory. Bestriding all of this has been the colossus of the pandemic, with a death toll that keeps spiraling up and up, approaching—at this moment—a quarter-million souls, with a concomitant, disastrous effect on our economy.

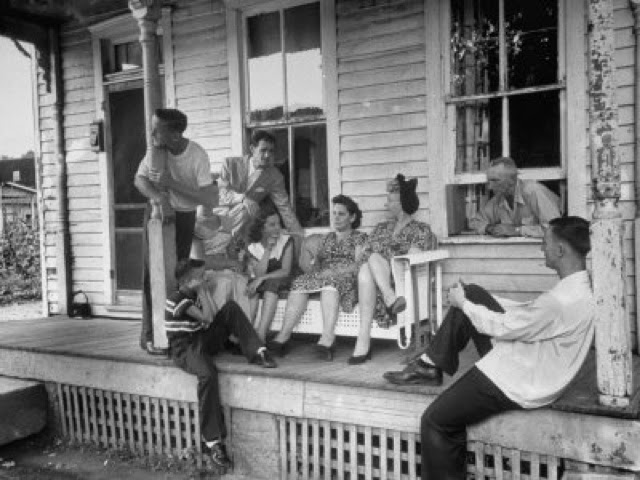

It’s tempting to say that the solution to all this literal and figurative storm and strife would be a return to that simpler, less-complicated way of life, when people gathered on each other’s porches in the evenings to pass the time in conversation, watching the evening light die as it filtered through the limbs of the elms. Those elms were long since carried off by blight, though, and our communication devices and our high level of connectivity are fixed realities now, at least until they’re replaced by the next new thing. We are not now what we then were, and we will again be altered, by and by. Things inevitably change, and change can be good or bad, or—more likely—good-and-bad. That’s the way of things.

What I find comforting in the face of this ambiguity is the thought of Megan and John showing up on the day after the storm, working shoulder-to-shoulder with Claire and me through a long, sweaty morning, for no other reason than that she knew me and knew I needed help. Whatever the truth of our tech-driven isolation from one another, when push came to shove on August 10 my neighbors’ impulse was to help one another.

When things get bad—as they inevitably do—when a derecho hits the Midwest, or a hurricane sweeps all before it in the Southeast, or the Western forests kindle and burn, or a demagogue in a position of power persuades us to turn on one another because of the variety of political sign we’ve got spiked into our lawns—it’s small and modest acts of heroism and our durable sense of community that get us through it. I feel a complicated pride when I think of that.

courtesy of Daphne Lockett's Blog, [Ramblings](http://daphnelockett.blogspot.com/2014/07/front-porch-sittin.html)](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2020-fall/grinnell_29549_OBJ.jpg)

Front porch society, as it used to be. Photo courtesy of Daphne Lockett’s Blog, Ramblings