Many people think of the prairie region as a treeless expanse of windswept grassland. But while it is true that the prairie is widely characterized by oceanic areas of wide open country, that country, before the advent of industrial-scale agriculture, was covered in a wide variety of plant species. These include grasses, but also many types of flowering plants, as well as multiple species of coniferous (evergreen) and deciduous (leaf-bearing) trees.

In recognition of this fact, in this issue of Rootstalk we are featuring a new addition to our regular “…of the Prairie” feature. In past we’ve highlighted prairie birds and prairie mammals; in this issue we’re leaving the animal kingdom for the realm of the plants, and offering mini-profiles of four trees that are native to the prairie.

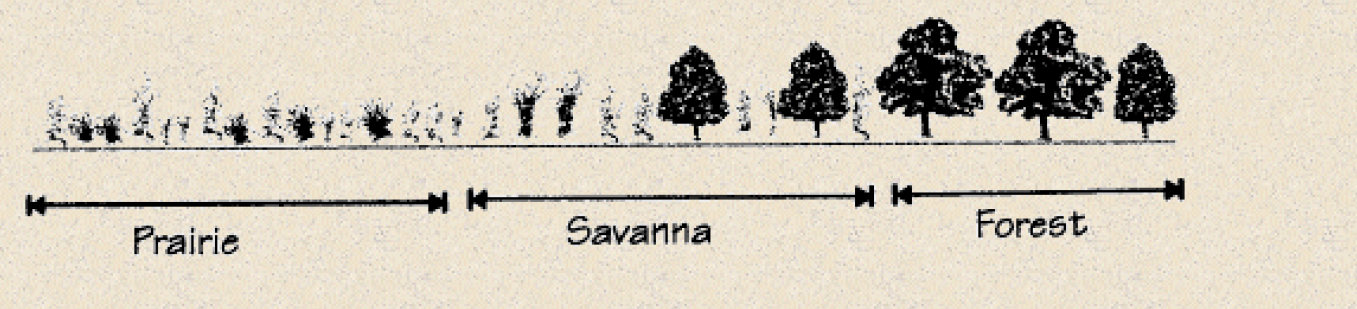

Illustration from ‘Managing Michigan Wildlife: A Landowners Guide,’ Sargent, M.S and Carter, K.S., ed. 1999. Michigan United Conservation Clubs, East Lansing, MI. 297pp.

The American Elm (Ulmus americana)

Flowers: March-April

Height: 40-98 feet

Elms are loved for their graceful, stately shape, with branches like spreading fountains, and their green leaves that turn gold in fall. Among the original prairie trees, elms are also essential in regulating ecological balance in floodplain forests.

Sadly, the American elm (Ulmus americana) can no longer be recommended because it is vulnerable to a devastating pathogen called Dutch elm disease. Caused by the fungus Ophiosthoma ulmi and spread by the elm bark beetle, this disease has wiped out hundreds of thousands of elms since its introduction to the Americas in the 1930s.

The biggest lesson learned from Dutch elm disease’s devastation is the importance of having a variety of trees along streets, in parks, and in home landscapes—this so that no disease or pest can kill such a large proportion of the trees. Arborists and foresters alike recommend diversified tree planting, with a particular focus on trees native to the region. (Description adapted from text. created by the USDA Forest Service)

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia commons

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia commons

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2020-fall/grinnell_29708_OBJ.jpg)

Photo courtesy of Homer Edward Price

The Burr Oak (Quercus macrocarpa)

Flowers: April-May

Tree height: 40-100ft

Known for their wide crowns and sizeable diameters, Bur Oaks grow chunky limbs and leaves that can be up to nine inches long. The largest of all native oaks, they also grow noticeably fringed acorns, giving the tree its other name, the Mossycup Oak.

The Midwest was once rife with oasis-like “oak openings,” fertile plots of land interspersed and lined with bur oaks, and these giants marked the edges of prairie lands further west, protecting the woodlands from prairie fires. Beloved for their strong wood and resistance to drought, these sentinels of the prairie deserve a round of applause. (Description adapted from text created by James R. Fazio from the Arbor Day Foundation.)

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2020-fall/grinnell_29710_OBJ.jpg)

Photo courtesy of Carl Kurtz

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2020-fall/grinnell_29558_OBJ.jpg)

Photo courtesy of the Missouri department of Conservation

The Cottonwood (Populus deltoides)

Flowers: April

Tree height: 65-130 ft

Cottonwoods grow naturally throughout the United States. but are important residents of the prairie ecosystem. You can recognize them at a distance by their massive height and broad, deeply furrowed trunks.

This useful tree species served as trail markers and meeting places for both Native Americans and early European settlers. Cottownwood trunks were used by Native Americans as dugout canoes. The bark provided forage for horses and a bitter, medicinal tea for their owners. Sweet sprouts and inner bark were a food source for both humans and animals.

In spring, female trees produce tiny, red blooms that are followed by masses of seeds with a cottony covering (Description adapted from text. created by USDA Forest Service)

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2020-fall/grinnell_29560_OBJ.jpg)

Photo courtesy of the Missouri Department of Conservation

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2020-fall/grinnell_29712_OBJ.jpg)

Photo courtsesy of Jason Sturner

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2020-fall/grinnell_29713_OBJ.jpg)

Photo courtesy of Carl Kurtz

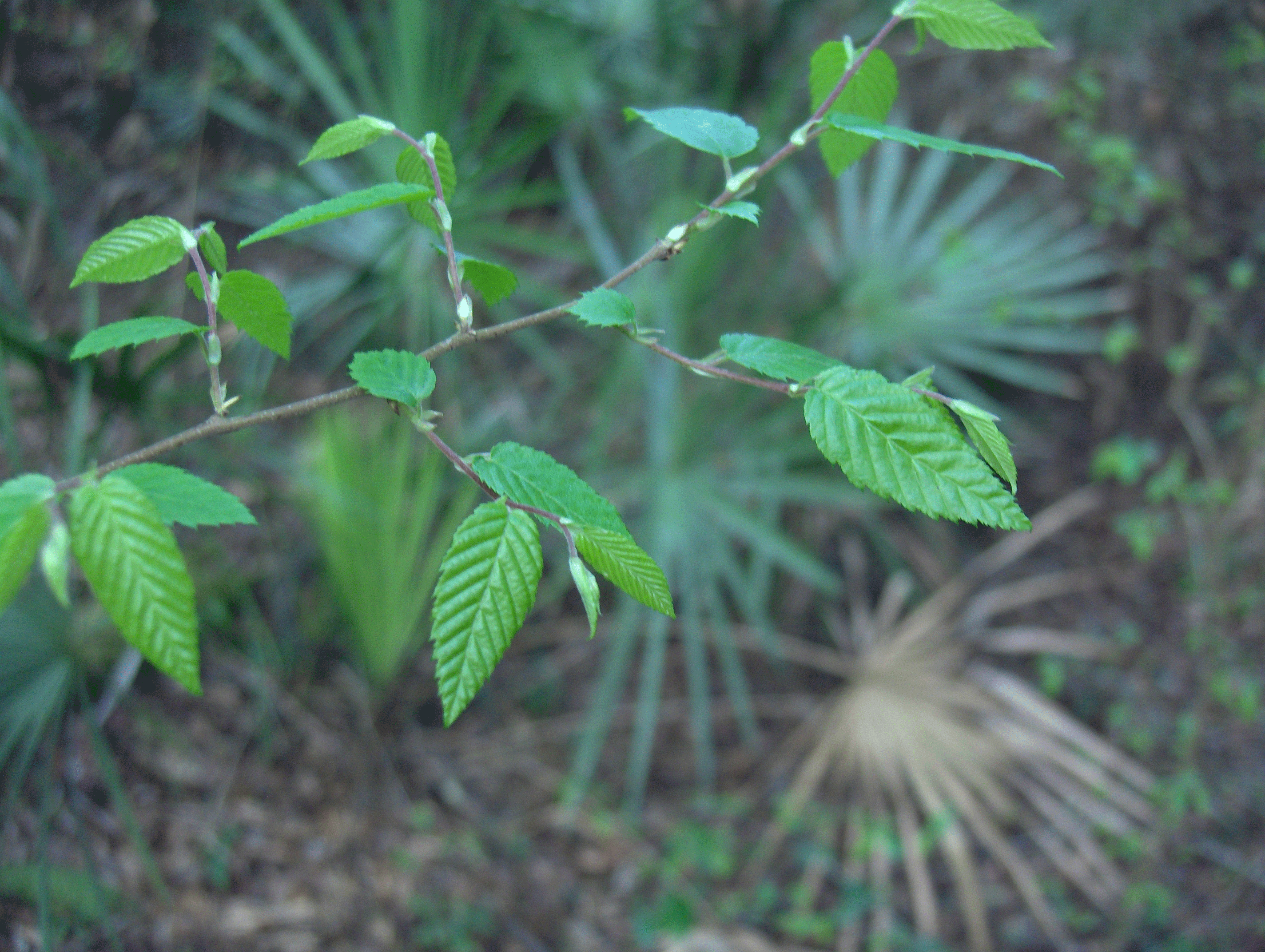

The Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

Flowers: April-May

Height: 75-100 ft

Hackberries are a stately mainstay of many Midwestern streets. A relative of the American elm, but not susceptible to Dutch elm disease, they grow tall and provide ample shade, as well providing clusters of drupes—small berries that serve as an important food source for wildlife, particularly birds and small mammals. These berries stay firmly attached to their twigs for longer than most boulevard trees and feed traveling birds throughout the winter. Hackberries are hardy and stand up well to the extremes of prairie weather, resisting drought, short-term flooding, heat, cold and ice. They’re also very resistant to pests and diseases; in fact the only problem they regularly have is with the formation of “witches’ brooms”—dense clusters of twigs which form when the tree is infested with a particular species of mite. Though odd in appearance, these do not much affect the overall health of the tree. (Description adapted from Silvics of North America from the U.S. Forest Service via its Southern Research Station).

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2020-fall/grinnell_29714_OBJ.jpg)

Photo courtesy of Breezy Hill Nursery

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2020-fall/grinnell_29715_OBJ.jpg)

Photo courtesy of Kathy Zuzek

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2020-fall/grinnell_29716_OBJ.png)

Photo courtesy of Carl Kurtz