When most people think of Minnesota food culture, church potlucks, state fairs, and lines of hot dishes are often what pops into their minds. Meals like tater tot hotdish, lefse, or freshly caught fish are in most Midwesterners’ brains. The Minnesota State Fair, the second-largest state fair in the country (after Texas), features a very unique brand of fair food. Fresh donuts, malts, and cheese curds are on the menu, along with a healthy dose of the iconic Midwestern fixture, corn. It’s found roasted in the husk, but also as an ever-popular flavor of ice cream.

Every iconic Minnesota food has its own unique origins, as immigrants and settlers have come into the state from all across the world. The culinary landscape is still in flux as traditions are revived, and new groups of people bring their foodways with them. New restaurants open constantly, from Sean Sherman’s first full-time decolonized establishment, the Indigenous Food Lab (slated to open in 2021) to the massive growth of Latino-owned establishments. From the indigenous people who first inhabited the land, now to the Somali and Hmong people who call Minnesota home, there is something for everyone.

Across Minnesota, new restaurants are opening, featuring foods of the many ethnicities that inhabit the state. Food, for many people, is home, and chefs from many groups are experimenting with blending the traditions of their homelands with classic “Minnesota food.” This allows them to feel connected to their past and share it with others. Minnesota food represents a crossroads between what is available from the land and the cultural traditions of those who settled there.

Ashinaabe and Dakota—Wild Rice and Berries

The Anishinaabe (also known as Chippewa) and Dakota people inhabited much of Minnesota until the early 19th century. Originally living along the Great Lakes, the Anishinaabe pushed the Dakota people south and west over time. As French fur trappers came into the territory, the added pressure pushed the Dakota further west, while the Anishinaabe forfeited much of Wisconsin and Northern Minnesota. Now, the tribes are scattered throughout different reservations in Minnesota and the Dakotas.

Many reservations are not located in places that were traditionally occupied by the tribes, and many living on reservations lack easy access to grocery stores. For many living on a reservation, canned and boxed foods are dietary staples, and traditional dishes have been rendered obsolete. However, some chefs are attempting to combat this slow fade of indigenous foods. Sean Sherman, an Ogalala Sioux chef and founder of the Sioux Chef, a group of indigenous people seeking to revitalize Native culture, is working to recreate traditional dishes with many tribes around the country. He encourages sustainable, native-harvested options. The recipe we’re reprinting here, which appeared in the New York Times cooking section on November 4, 2019, uses wild rice and berries, which are endemic to Minnesota and are common ingredients in many recipes from the region. Whenever possible, Sherman encourages using Native-harvested ingredients, such as wild rice from Native Harvest, which prioritizes native harvesting methods.

Photo courtesy of Nicki Kreutzian

Photo courtesy of Sean Sherman

Oglala Lakota Chef Sean Sherman, founder of The Sioux Chef, is decolonizing our food system. From growing up on Pine Ridge to an epiphany on a beach in Mexico, Chef Sean Sherman shares his journey of discovering, reviving and reimagining Native cuisine.

INGREDIENTS

1 ¼ cups long-grain wild rice, rinsed

½ cup mixed dried berries

3 tablespoons maple syrup

¼ cup whole hazelnuts, crushed

2 tablespoons hazelnut oil

Fine sea salt and whole chive stems for garnish

METHODS

1. Heat the oven to 350 degrees.

2. In a large saucepan, bring 5 cups water to a boil over high. Stir in 1 cup wild rice along with the dried berries and maple syrup. Once the mixture comes back to a boil, reduce the heat to just simmering, cover and cook until the grains begin to open, 20 to 40 minutes, checking doneness after about 20 minutes. (The rice is done when it has opened slightly, is tender and has quadrupled in size.)

3. Drain the excess liquid from the rice.

4. Meanwhile, toast the hazelnuts. Lay the hazelnuts in a single layer on a baking sheet and toast them until the skin blisters and cracks, and they begin to smell nutty, 10 to 12 minutes. Transfer the nuts to a clean dish towel and massage them aggressively to remove most of the skins. Crush the nuts directly in the towel using the flat side of a knife.

5. Add the remaining 1/4 cup rice to a dry skillet and cook over high heat, shaking the pan, until it begins to darken and about half of the kernels have popped, 2 to 3 minutes. Remove from the heat.

6. Drizzle the boiled rice with the hazelnut oil and season to taste with salt. Garnish with the popped rice, hazelnuts and chives.

From Sean Sherman via NYT Cooking

Somali Influences—Pear and Cardamom Cake

Much contemporary Somali cooking was influenced by Italian colonists who came to Somali in the 1880s. Spaghetti, for example, is a staple in Somali kitchens. One finds many similarities between Somali and Italian cooking, although spices or cooking methods often differ. Curries, stews, and protein over rice or spaghetti (sometimes both) is the basis of many Somali recipes, usually with a homemade hot sauce. An equally important aspect of Somali cooking is the banana. It is served with nearly every meal, and eaten with rice and stew. Every Somali kitchen includes cardamom. Cardamom cookies are a staple, and Somalis consume the second most cardamom per capita, after the Finns.

Even just a few years ago, Somali cuisine was difficult to track down. The first groups of Somali people came to Minnesota in the 1980s, with a majority arriving in the late nineties. However, the Somali language began to be written down only in the 1970s, and because of this there has been only one Somali cookbook in English, called Soo Fariista/Come Sit Down: A Somali American Cookbook. Most family recipes were never written down, just passed along orally. In 2018, a group of Somali teens, most of them first-generation immigrants, set out to create a new Somali-American cookbook. This book’s authors followed their parents around the kitchen, documenting cooking processes that had been passed down from generation to generation, and which were available in print only on little-visited internet sites. The authors’ ambition was to make these foodways available in everyone’s kitchen.

Photo courtesy of Abderazzaq Noor

Abderazzaq Noor started The Somali Kitchen because it was a great way to combine his passions—food, cooking, eating, writing and Somali culture. His love for food and cooking came from his beloved parents, who ran a popular Somali restaurant.

INGREDIENTS

2 ripe pears, thinly sliced

¾ cup brown sugar

¾ cup white sugar

¾ cup butter, room temperature

½ teaspoon ground cardamom

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

2 large or 3 small eggs

Pinch of salt

1 ½ cups flour

2 teaspoons baking powder

½ cup milk

METHODS

1. Heat the oven to 180 degrees C (350 degrees F) and butter a 9 inch round spring cake pan.

2. Sift the flour, salt, baking powder and cardamom and set aside.

3. Melt one portion of the butter in a pan. Add the brown sugar and stir until the sugar has melted. Pour the mixture into the prepared cake tin and ensure it spreads to cover the bottom evenly.

4. Arrange the pear slices in a circular shape around the pan and finish with any remaining slices in the centre.

5. Mix the remaining butter and white sugar and beat until creamy. Adds the eggs and vanilla and whisk for a couple of minutes. Add in the flour and milk and combine gently.

6. Spoon the batter over the pears in the cake tin and smooth over.

7. Bake for about 40 minutes, until done.

8. Cool and gently turn the cake onto a plate.

From Abderazzaq Noor via The Somali Kitchen

1920s Settlers—Minnesota Bean Pot

As America pushed to settle the West, more and more people looked at the Midwest and decided to settle down. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Twin Cities experienced rapid growth, due to the high prevalence of industrial jobs, especially in wheat mills. Many German and Scandinavian immigrants settled throughout Minnesota, both in cities and small farming communities. Minnesota was geographically most similar to their home countries, with mild summers and long, harsh winters. They brought the food traditions that sustained them through those long nights and found that many vegetables they grew back home flourished in the Minnesota Climate.

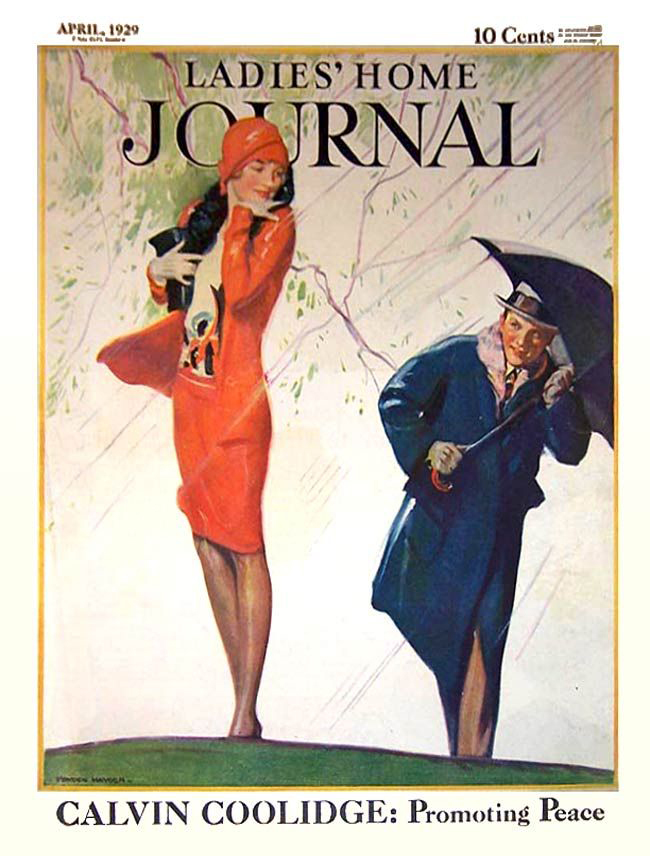

This recipe, from a “Mrs. A.P.C.” of Bemidji, comes from Ladies Home Journal Vol 46 Issue 4, published in April 1929, just months before the stock market crash that heralded the Great Depression. In this time of surplus, many people were able to afford prepackaged foods from stores, and small personal gardens fell somewhat out of favor as people flocked to large cities. This was the start of more cultural homogenization, and as the article notes in its title “Minnesota, Border State, Shows Foreign Influence”. While rather unassuming and, mainly consisting of meat, crackers, and potatoes or carrots, the recipes are heavily indicative of the food culture and landscape of the prairie region in the early 1900s.

Ladies Home Journal, April 1929

INGREDIENTS

1/2 pound kidney beans

1 medium onion, sliced

1/8-pound fat pork

½ pound ground beef

6 small red peppers

1 quart of canned tomatoes

3 teaspoons of salt

METHODS

1. Wash the beans and soak overnight.

2. The next day, cook the onion and pork until slightly browned, then add the beef, peppers, tomatoes, salt, and drained beans. Add one quart of water.

3. Bring to a boil and let it cook for two and a half hours, until the beans are tender. Remove the peppers and serve with crackers.

From Mrs. A.P. C. via Ladies Home Journal

Photo courtesy of Nicki Kreutzian

Hmong Sweet and Spicy Cucumber Salad

In the 1970s, the Hmong people began immigrating to the US, fleeing wars in their homeland of Laos. Now, the Twin Cities have the largest concentration of Hmong people of any city in the United States. Making their home in the Midwest allowed them to bring their culture and food traditions with them. A decade ago, as the first Hmong restaurants began opening in the cities, Hmong restaurants did not capture the true Hmong foodways. The menus often had everything from cashew chicken to pho and everything in between. It seemed that there was a view that it was “Asian food”, and Minnesotans had not quite seen how it set itself apart.

Over time, more children grew up and began to blend their Hmong roots with their Midwestern upbringing. Today, Hmong food has carved its distinct niche in the Minnesota food scene. For chef Yia Vang, food, and in particular, hospitality is the backbone of Hmong culture. It is a way to connect, to show warmth, and to appreciate history and how far families have come. For many restaurants, the food that appears on their menus is not of their invention, but rather something their parents made for them growing up. It is comfort food, at its essence.

Yia Vang was born in a Thai refugee camp, came to the United States at five years old, and eventually arrived in the Twin Cities as part of the largest urban Hmong population in the world. He cooked at Nighthawks Diner & Bar, Borough, and Gavin Kaysen’s Spoon & Stable before starting Union Hmong Kitchen, and serves as a passionate, tireless, funny, and forgiving advocate for Hmong food

INGREDIENTS

½ bunch cilantro

1 small shallot, finely chopped

1 garlic clove, finely grated

2 Thai chiles, finely chopped

¼ cup tamarind concentrate

2 Tbsp. fresh lime juice

2 tsp. fish sauce

6 medium Persian cucumbers or 1 large English cucumber, some peel removed in thin alternating strips, halved lengthwise, thinly sliced on a diagonal

1 cup cherry tomatoes, halved

Kosher salt

Store-bought fried shallots and coarsely chopped salted dry-roasted peanuts (for serving)

METHODS

1. Thinly slice cilantro stems until you have about 2 Tbsp. and place in a large bowl. Coarsely chop remaining cilantro; set aside for serving.

2. Add shallot, garlic, chiles, tamarind concentrate, lime juice, and fish sauce to bowl with cilantro stems and mix well. Add cucumbers and tomatoes, season with salt, and toss until everything is nicely dressed.

3. Transfer salad to a platte and top with reserved chopped cilantro, then fried shallots and peanuts

From Yia Vang via Bon Appetit

Photo courtesy of Nicki Kreutzian