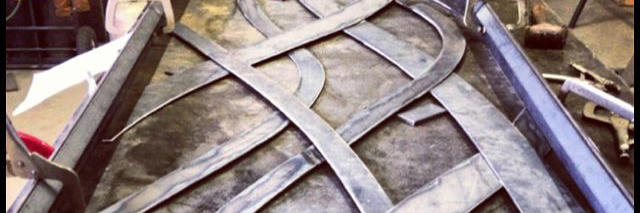

Art is the one thing that mystifies me the most; it takes me to a place inside of myself where anything is possible. I am bringing the unseen and the intangible into form—all artists are. The imagination is a portal that is endless and we all have access to this inner realm where the unconscious can be tapped. I chose blacksmithing and steel sculpture as my primary medium because it’s tangible. I need to build things with my hands and feel them. Working with fire connects me to the beginning of humanity where some of the very first tools were made. Bending and manipulating steel reminds me that even the most rigid things in life can soften and be reshaped.

—Sculptor Betsy Bower

Until recently, self-taught sculptor Betsy Bower lived where what is referred to elsewhere as an “art community” didn’t really exist. Casper, Wyoming—Bower’s hometown and the hometown of LGBTQ icon Matthew Shepard—is a tough place to build an art career.

In the following interview, Rootstalk Associate Editor Millie Peck talked to Bower about the challenge of becoming an artist in a place where making a life as an artist is a challenge, and about what continues to drive her artistic vision.

Rootstalk: Tell me a little bit about how you got started as an artist?

Bower: I grew up welding in my dad’s shop:, Bower Welding and Ornamental Iron. When I was 13, he started taking me down to Utah to go to blacksmithing workshops to learn from some of the best blacksmiths in the world who were demonstrating. Then he built a little smithy—that’s what they call it, like a blacksmithing shop in the back of his shop—and started collecting tools ‘cause he was fascinated by it. So, I would practice what I learned in those seminars, in those workshops. I got really hooked on it, I really loved the art of bending hot steel and manipulating it and working with it.

My senior year of high school I went to Japan as an exchange student. We stayed at my cousin’s house in Denver the night before I flew out, and he was a metal artist as well. He was a jeweler, and he built these amazing sculptures and metal wearable art, like chastity belts. His work was amazing and so I thought that maybe I would get into jewelry or something like that. I knew that I wanted to work with metals, and I thought that maybe I would get into jewelry because I could make money that way.

Then in Japan I studied different art forms, like pottery, calligraphy, and flower arranging. In Japan there is an art to absolutely everything, and I was so amazed by that. It was so beautiful to experience a country that valued the little things, just everything felt so alive and it’s so cute. They put little faces on all sorts of inanimate objects and things like that, it just made everything feel more alive. When I came back, I wanted to make things feel alive. So, I got more into the style of making organic forms.

I went to Casper College and made jewelry. I started working for my dad on the side, and then starting to do my own jobs too, ‘cause I didn’t think I could make a living doing art or doing sculpture, or doing metal art, but then I started to. I started to make money doing it, and so I was like, “maybe this is possible?” I went to Burning Man in 2009, and I was blown away by the sculptures I saw there and the things that people would create, so I just decided that it was possible.

Rootstalk: How did you gain recognition as an artist?

Bower: When I came back from Burning Man, I did an art show and one of the pieces inspired Shawn Rivett, and we started working together and we started building things for his gallery in Casper, which is now closed, called Haven. Doing work for him got me more known, like I got into this 307 Magazine. I played bass in a band, the Foreign Life, and my bandmate, who was the drummer, wrote for 307 Magazine. He did a whole feature on me and that went Wyoming-wide. Then the Wyoming medical center got ahold of me. They wanted a piece, like a sculpture for their lobby and some other pieces around the hospital. One by one I just started having pieces go up all over Casper and in other places in Wyoming.

Rootstalk: Do you have any formal art training?

Bower: I’ve always been creative; I guess that’s as formal as it gets. I guess these blacksmithing seminars count too. I have a flower arranging certificate from Japan. I went to Casper College and I took some art, but I didn’t pursue a degree because the professors would say to make money as an artist you have to teach. And I was just like “What that’s bullshit! No…” So I just decided it wasn’t useful to get a degree if I wanted to do what I wanted to do because there wasn’t a curriculum for it. I took three-and-a-half years of just art classes and music, and I spent a semester in Hawaii studying and I took pottery and different things there and drew inspiration from the different art forms I saw there. I mean for a minute my backup plan was to become a tattoo artist; I would joke with my mom that that’s what I wanted to be, just to sorta be a rebel. But no, I just decided that it wasn’t necessary for what I wanted to do. I didn’t want to do what other people were telling me to do to get to where I wanted to go, because I didn’t know anyone else who was where I wanted to be.

Rootstalk: Your dad really helped you jumpstart your career, how does he feel about you being an artist?

Bower: My dad doesn’t talk a lot, but there was another interview I got to do — for I think the Casper Star Tribune or something—and one of the writers went and interviewed him and so I got to read in the article what my dad said, and it was things he never really said to me. He said, “Betsy can see around the corners.” I think what he meant by that was I can visualize something in 3D, and I guess I thought that was something everyone can do, but maybe not everyone can do it. I know that some people are verbal processors or they think in sound or something like that, but I definitely visualize things and think in 3D. He noticed that I can kinda like make decisions about a piece while just thinking about it. He expressed being proud of me. I think he always wanted and supported me going in the direction of my dreams and doing art because he never, like, complained about me leaving messes in his shop, I mean his other employees would. He never stopped me from just doing what I wanted to do and he always let me use his scrap steel or sometimes his new steel and do whatever I wanted with it. He always took me to blacksmithing seminars where I got to learn how to make things. Together we made this little torch—like a pedal torch where you press a pedal with your foot and then the fire blows up so you can have your hands free to use things and hold things over the fire. So yeah, he’s awesome and has never been super verbal. He has always just acted on it and helped me sort of develop my skills because he’s always believed in me.

Rootstalk: How did you stay inspired living in a town with such as small art scene? How did you find the drive and motivation to keep going?

Bower: I have this mind that keeps going on its own. Also, definitely from traveling and I mean even just nature. Anything really can inspire me, I’m just an excitable person. Burning Man for sure blew my mind wide open and then helped me through the possibilities of like wow, if I only lean into something I really want to do and then just do it, then it’s possible. In a way I kinda became a hermit while I was in Wyoming and just made my studio my own little fantasy land and did whatever I wanted there. I had the focus to do it because I’m definitely an individual learner and thrive when I’m like able to just have silence and can create my environment around me, so that I can be alone to think about and contemplate things and then do it. I never loved classroom settings and things like that. I hated school growing up because it was just too distracting to be around everybody else, and if I did not sit in the very front of the classroom, I wouldn’t do well in the class. So, think being alone is part of what fueled me doing anything at all. I lived in Seattle for a little bit, and there was so much to do, there are endless things to do with endless numbers of people with interest to do it with, so I didn’t get any work done there. So when I was in Casper I was like, Hmm there’s nothing to do here, I mean not nothing; you can definitely go outside and enjoy nature and, you know, go to little coffee shops and stuff and hit up the few Galleries and museums that they have there. But like really, there’s not an endless number of things to do, so it gave me the focus to actually get some work done and entertain myself while doing it with my own company.

Rootstalk: What was it like being a queer artist in Casper?

Bower: It was hard staying in Casper. Casper is the hometown of Matthew Shepard, and so you’d think there would be more equality there, but really, there wasn’t anything. I kept searching for an outlet to meet my people; I felt really alone. And there wasn’t really anything. PFLAG (Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) was trying to do picnics in the park that I would go to. I made this lyra stand apparatus to hang my trapeze from and I performed one year. They would just sort of tuck it in the back of Washington Park where you couldn’t really see it. I would always invite friends to go, but no one would show up. It was just the same people who always went, which wasn’t many. I mean for them it was, for them 50 people is like “Wow, look at what we did.” And I’m thinking “This isn’t enough. There are people wanting to take their own lives because they feel so alone or like there is no one there to understand them and there are no outlets for queer people. They can’t be themselves, and they feel like they have to conform to the way that everybody else is, and that’s just not how it needs to be. So I started going to PFLAG meetings to ask, “Why don’t you advertise it, why don’t you make something of this?” But nobody really listened to me, and so I finally got some friends to go with me one time, and we just sat at this table and then we finally had some gravity. I was able to say, “We need to make the picnic in the park something different, something bigger, like create booths, actually advertise it so that people actually come.” and then they listened. I got my friend Mallory to be a part of it with me, and we started planning something bigger, and then it worked and it took off. Eventually I got to walk in our little pride parade with Matthew Shepard’s father and do a little speech across from the courthouse. TV came and they interviewed us, and they were like, “This is how you do pride in a small town in America, yes!”

I guess I felt like if I’m gonna be here, I want to do something that the community needs. It felt really uncomfortable because I grew up in a religious, Mormon family, and it was totally unacceptable to be out and queer, but I did it anyway. I just decided that it was worth the risk. If I had to make myself a target so that other people could feel accepted and loved and know that they have a place infthe world, where they can be themselves, then it’s worth the risk. I feel like Burning Man taught me that and just being around other people who were totally, authentically, radically themselves.

Rootstalk: Do you feel like art was a big part of how you expressed your identity?

Bower: Yeah it was, and I didn’t realize. One of my teachers was talking about the concept behind art, like really creating something meaningful in every art piece. They emphasized that very art piece means something, and they would psychoanalyze the pieces. At first, I thought it was all bullshit; I don’t think about that at all when I create something, and that was the story I told myself. Then one time I had finished this tree piece with pipes that were bending, this organic form, and it just has this balance to it. It went in my friend’s gallery, Haven, and it was like actually structural and held up the staircase above. I was having a couple drinks with one of my fellow artists, who was a graphic artist, at this party and it was probably one in the morning, and he was just looking at it and said, “This is what I see in this piece.” To him it expressed something, and when he reflected that back at me, it was like he saw into my soul a little bit in the way that he described it, and I thought “Whoa, I actually am expressing something in my art, and I just didn’t have the intention going into it, it’s just what came out of me.” And so, I realized that it doesn’t really matter whether it’s intended or not, it comes through. A couple of days ago, I did a little piece for a show, and one of the presenters was like “I see death in your art.” And I said “Yeah, that’s a piece of it; that’s part of its beauty; there’s dark and there’s light.”, and I kind went into explaining that, but it’s just like my identity does come through. That’s what I love about it and that’s where I’m going next with some of my art to really dig deeper into the emotions that do generate behavior in me and society and create from that space, from those feelings.

Rootstalk: What’s your biggest dream as an artist?

Bower: My biggest dream is to take art to Burning Man, and I’m currently working on an art car called the “Goth Cart”. It’s like a golf cart that I’m turning into a gothic version of itself. I’m collaborating with other artists to make it into this wild thing, One one of my neighbors has the world’s fastest jet engine bus so he works with fire, so I’m gonna have this thing, like, blow fire out of the top of it. And then I have another neighbor who makes cars artistic, so he’s helping me, he gave me a bumper the other day so that I could cut it down and make it look super badass.

Rootstalk: What are you working on now?

Bower: What I’m working towards now is developing an art community, and I’m trying to figure out how to do it online. Before Covid I would have these art parties where I just invite people over to my studio and teach them skills like plasma cutting, welding, or how to use the forge and blacksmith. I’ve done flower making workshops where people make roses together, to get them fired up, to get them excited to use their creativity. They took away funding from the school system for art classes, which is to me, devastating, because you put your money where you think there’s value. If they take away money from art, that’s telling the world, or our country, that art and creativity are not valuable. So, yeah, I just want to make it my mission to bring that back, to inspire people to realize how valuable it is. Because it is such a healing, cathartic thing to do art, the process of making art is healing, and looking at art can be healing and inspiring and meaningful. Without art there is less meaning to life. I think every person needs to know that if they can harness their gift, whatever it is—poetry, writing, creativity, painting, sculpture, whatever it is—if they can develop that gift, they can bring more meaning to their lives.