During the eight years that I lived in Coats, Kansas—from 1934 to 1942—the town existed to support the farms in the area, and the well-being of the farms was of crucial importance to everyone in town. The farmers, in turn, depended entirely upon wheat, for it was the only cash crop. Wheat was planted in the fall and sprouted and grew to a height of a few inches before winter, then died down during the winter months and began to grow again in spring. As stalks became taller and the grain began to ripen, the wheat became more and more vulnerable to weather damage, for the heads became heavy and the dry stalks became brittle. Five minutes of hail could completely destroy a field of wheat, cutting down all the stalks and beating grain out of the heads. An hour or so of rain and wind could flatten the field and make the crop difficult, if not impossible, to recover.

When the wheat was ripe, everything else in the community took second place to the harvest, which required about two weeks. In a town as small as ours, churches that had Wednesday night services canceled them during harvest time, and all other non-essential community activities were suspended during the period of wheat harvest. It was a time of high drama, when everyone in the community watched the weather if clouds began to threaten. I am sure that in a town whose population was measured in thousands, many people would have been unconcerned about the wheat harvest drama, but in a town whose population was measured in hundreds, few could have been unaware of the tension at wheat harvest time.

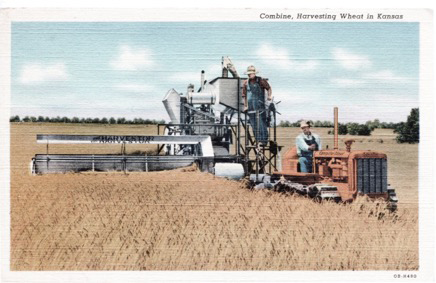

The machine that was used to harvest wheat was the combine, so called because it combined three separate harvesting operations: reaping, threshing and winnowing. At that time, most combines were pulled by tractors; self-propelled machines were just beginning to appear. A three-man crew was required to harvest wheat: a tractor driver, a combine operator, and a truck driver to haul the grain from the farm to the elevator in town. I do not recall ever knowing of a woman working in the harvest field, so if a farmer did not have at least two sons old enough to work with the machinery, he needed to hire help for harvest. Many people in the community who could spare time from other jobs were pressed into service. My father, a minister and pastor, probably worked in the wheat harvest every summer that we lived there, and as soon as I became old enough, I also was employed during harvest. Their absence from the field did not indicate that the women in the family were not working, for they were preparing and then cleaning up after a large meal at noon. Always the crew stopped at noon to go to the house for a dinner that typically included fried chicken, mashed potatoes and gravy, green beans, bread or freshly baked biscuits, and pie.

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2021-spring/grinnell_29923_OBJ.jpg)

Photo courtesy of Thecombineforum.com

Self-propelled combines that one sees today have the cutting platform across the front of the machine, and the operator sits in a cab high above the ground and enjoys his air conditioning and perhaps a sound system. When a combine was pulled by a tractor, the tractor was directly in front, and the cutting platform extended off to the side 12 or 15 feet. The cutting platform consisted of a sickle bar at the front to cut the grain, a reel that rotated to knock the cut stalks back onto the platform so they did not fall forward onto the ground, and on the platform itself, and either a moving canvas belt or an auger to carry the grain into the machine. Inside the machine, stalks of wheat passed through a beater which beat the grain out of the head and reduced the stalks to coarse chaff. The mixture of grain kernels and pounded stalks went onto a separator which shook to cause the kernels to fall through a grill into a collecting pan and also gradually walked the chaff to the back end of the combine where it was discharged onto the ground. An auger transported the grain kernels from the collecting pan to a bin on the side of the machine high enough that a truck could drive under it.

Inevitably, some kernels rode to the back of the machine with the pounded stalks and were lost, and that loss increased as the quantity of stalks being processed became greater. Therefore, it was important that the cutting platform carrying the sickle bar be raised as high as possible without missing heads of grain. The operator stood at just about the level of the reel and raised and lowered the platform with a lever or with a wheel, depending upon the make of the machine, to try to get all the heads with a minimum of stalk. When the combine was in motion cutting wheat, the operator had to be constantly alert to raise the platform when the wheat was tall and lower it when the wheat was short, always being aware of the danger of running into the ground. Because the operator stood at approximately the level of the discharge, when the wind blew dust from the discharge at the back of the machine toward him, he worked in a cloud of dust and groundup wheat stalks.

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2021-spring/grinnell_29919_OBJ.jpg)

Photo courtesy of Thecombineforum.com

If there had been a heavy dew during the night, the combine crew could not begin work until the wheat had dried, because if the heads were damp, kernels would not be beaten out in the threshing process. That might mean that the crew could not actually enter the field and begin work until about 9 o’clock in the morning. The time before that was spent putting fuel in the machines and greasing the bearings of the combine. Most of the bearings were not sealed, and every day the operator had to pump grease into them before work began. The operator used a grease gun, which is similar to a caulking gun, and attached the nozzle to a small nipple on the bearing called a zerk. (The name is eponymous—the system was invented by Oscar Zerk.) The grease was put into the gun from large buckets which the farmer bought in preparation for harvest season. Making up for the late start in the morning, crews often worked until the sun was low on the horizon. I think that crews I worked on usually stopped by about 7pm, but my memory on that is hazy. I do remember that I was always ready to stop before the farmer was. Sometimes tractors and combines were equipped with lights so that they could work until after dark, but I recall seeing combine crews using the lights only a few times.

My first experience working in the wheat harvest came the summer I was fourteen years old, when I drove the truck hauling wheat from the farm to the elevator in town. I was working for a farmer who lived a few miles out of town, and I think that my father also was working for the same man, probably as a combine operator. When the combine bin was full of wheat, the machine stopped, and I drove the truck up next to it so that the spout of the bin was over the bed of the truck. One of the crew opened the gate of the bin, and wheat ran into the truck. When I had a load, I drove into town. I had no driver’s license at that age, but we were far from any highway that was likely to have a patrolman, and what I was doing was not unusual.

At the elevator I drove the truck onto the scales, so that all four wheels were on the scales platform, and the elevator attendant weighed the truck and its load. Sometimes the attendant took a sample of the grain to check for moisture content. I then drove into the elevator itself and positioned the truck over a grill made of steel rods with the front wheels of the truck on a hydraulic lift. Two or three elevator employees worked at that station, and one of them opened the back gate of the truck so that the grain could run out and then operated the hydraulic lift to raise the front end of the truck to encourage the grain to flow. I could stay in the cab and ride up with the lift, or I could step out of the cab and stand aside until the grain had been dumped. Usually I preferred to get out because I did not enjoy riding up. I then drove the truck back over the scales so that the empty weight could be recorded, then returned to the farm for the next load.

In 1942, I moved with my parents from Coats to Gypsum, Kansas, and in 1944, during my first semester of college, my parents moved from Kansas to Nash, in northern Oklahoma. My pattern of working for farmers in the community was broken by the move. However, during my freshman year at college I lived in a dormitory with a roommate I had never met before. At the end of the first year we both needed to work during the summer, and at my suggestion we decided to follow the wheat harvest. I was able to make arrangements for us to get work in the Nash community, where my parents now lived, which was still wheat growing country even though it is in northern Oklahoma, and also at Gypsum, the community where I had once lived.

My roommate and I went as a team, although at one stop we went to separate farmers. He had never done any work on a farm, but I thought that he could drive a tractor, and I had had enough experience that I offered myself as a combine operator.

We worked near Nash, Oklahoma, for about two weeks. We then moved to Gypsum, Kansas, and worked for another farmer for about two weeks. When the harvest was done there, we took a bus to Oberlin, Kansas, went to the courthouse, where farmers were coming to hire men, and found employment. After the harvest was done there, we went to Sidney, Nebraska, and my memory is that we hitchhiked on that leg of the trip. There, again, we found employment and worked throughout the wheat harvest. The next jump would have been into the Dakotas, but my roommate needed to get back for a commitment in Oklahoma, and so we returned home.

At every location, the farmer provided us room and board for the time that we worked for him. I have no idea now what we were paid, and I do not think that there was any explicit discussion of the value of our room and board for the time that we were at each farm.

I have only vague memories of the routine work, but three experiences stick in my mind vividly:

(1) My lips became painfully chapped from the sun, even though I always wore a large straw hat while working in the field. I do not think Chapstick was on the market yet, and I did not have a chance to get something like Mentholatum or Vaseline that would have soothed my lips. As a substitute I used oil that was intended for the crank cases of our machines. I remember how it tasted, but I do not remember how well it worked on my lips.

(2) When we were hitchhiking, we once were picked up by a young couple in a coupe with a rumble seat, and we rode together in that seat all afternoon. It was my only experience with a rumble seat.

(3) Late one evening we arrived at a town where we planned to spend the night, and we decided that instead of spending money for a motel room, we would sleep outside. We walked out from the edge of town a short distance and bedded down in the ditch, with dry weeds smoothed under us as a mattress and also to protect us from the cold ground. So far as I can recall, we slept well.

‘This postcard shows what I think is an International Harvester combine of the sort that I worked on. This looks very much as I remember the combines that I most commonly saw, although I do not recall ever seeing a Caterpillar tractor in a wheat field. My memory is primarily of combines with the cutting platform on the night-hand side pulled by tractors with rubber tires.’ Postcard from the collection of Beryl Clottfelter

My roommate went to a different college in the fall, and I lost track of him, and several attempts to locate him were unsuccessful. More than fifty years later he contacted me, and we exchanged a few letters before he died. When we began discussing our summer following the wheat harvest, I was amazed by his recall of details that I had completely forgotten, and I asked him if he had kept a diary or kept notes and how he could remember so much better than I. His response was, “You probably do not remember the details of our ‘wheat harvest summer’ because it wasn’t the HUGE experience in your life that it was in mine.” He had never done anything similar before and did not do it again.

I realize now that we were near the end of an era. When combines were first introduced, they were pulled by horses or mules. I never saw a combine pulled by horses, for that era had ended completely. Then for several years they were pulled by tractors, and we were at the very end of the tractor period, for already we were seeing self-propelled combines. The war had accelerated the introduction of self-propelled combines for several reasons, including the reduction in steel in manufacture and the reduction in manpower to operate in the field, but once they were well-established they changed the pattern of cutting wheat in the Great Plains. The owner of a self-propelled combine could load it onto a truck and make the jump ahead to the next region where wheat was becoming ripe. Contract combining became common – crews with combines and trucks, sometimes several of each, moved from community to community contracting with farmers to harvest their wheat for them. Some crews working that way traveled from Texas to Canada cutting wheat all the way, and we saw spectacular pictures of fields being cut by several combines at once, chasing each other around the field.

‘A common combine was the Baldwin Gleaner; the one shown here is a 1938 model, and it probably did not differ much from the ones that I saw in the early 1940’s. I think that by the time I was doing that work, most tractors had rubber tires rather than the lugs and steel shown on this tractor,’ Photo courtesy of Twin City historian tony Thompson

After college, I moved away from wheat country and have never lived there since, and so I know nothing about practices today. When I see the humongous combines sitting in the dealer’s display yard in Grinnell with an air-conditioned cab to protect the operator and perhaps GPS to guide the machine, I cannot imagine what the experience would be like, for my memory is of dust and dirt and noise.

Even though my knowledge of the technology is 75 years out of date, I feel certain that two things that I remember from my experience in a small town in wheat country have not changed: the sense of urgency felt by everyone in the community about getting the crop harvested, and the anxiety of the farmer on a summer afternoon when the wheat is almost ripe and thunder clouds roll in with a greenish tinge that often presages hail. Until the grain has been cut and stored in bins, the crop is at the mercy of Mother Nature, no matter what the technology of harvesting may be.