In 1945, at Iowa’s State Training School for Boys in Eldora, Iowa, seventeen-year-old Robert Miller shoveled coal all day long as punishment for an alleged escape plot. When he tried to quit working because the oppressive August temperature had drained his strength, guards at the school tried to force him to continue and, when he refused, the guards beat him to death 1 with an iron rod taken from a “harness tug.” 2 The local coroner, after an autopsy, ruled Miller’s death a homicide. 3 The day after the murder, 179 boys ran away from the school, 4 and the governor of Iowa called in the National Guard to restore order. The National Guard remained at the school for an additional four months.

The boy’s murder happened for multiple reasons. Otto Von Krog, the school’s Superintendent, was in charge of a system that controlled children through force and coercion. This was also during World War II, when most qualified men of military age had joined the army, 5 and so Von Krog had to run the school with a staff of unqualified, inexperienced men. Under these conditions of harsh discipline and quasi-military training, incidents like Robert Miller’s murder became all too possible.

After Miller’s death and the subsequent investigation, the superintendent, the dean of boys, (who directly controlled corporal punishment) and the deputy superintendent had charges filed against them, ranging from conspiracy to second degree murder. 6 The cottage manager who supervised the dormitory in which Miller was housed and was alleged to have administered the beating that killed the boy, was charged with second degree murder, as was one of the guards who allegedly held Miller while he was beaten. Still another cottage manager who took part in the beating was charged with assault. 7

At trial, the guards admitted intimidating Miller with an axe handle while forcing him to work on the coal pile, until he collapsed from heat exhaustion. However, after a lengthy trial, the conspiracy charges against management were dropped, and the charges against the two cottage managers were reduced from murder to assault and battery. 8 This was despite the fact that numerous eyewitness accounts blamed three officers for beating Robert Miller while other officers held him, and also testified that these same guards denied him medical attention. The murder of Robert Miller is evidence of what can happen when the foundation of an institution is discipline backed with physical punishment. What remains unanswered—which will be explored in the balance of this essay—is why state government allowed this regime to become so prevalent at the State Training School for Boys that, eventually, every aspect of the school revolved around “rehabilitation” through force.

Progressivism’s Failed Promise

It is helpful to consider Miller’s murder in the context of the Progressive Era in American history. The Progressive Era lasted from 1870-1920, a period during which activists tried, but failed, to remake Americans into better individuals. In his book A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 9 historian Michael McGerr blames crusaders drawn from the nation’s middle class for the failure of this movement. He holds that the Progressives promised a utopian society but delivered nothing but unrealistic expectations.

David J. Rothman, in his book Conscience and Convenience: The Asylum and Its Alternative in Progressive America, 10 offers a poignant history of the juvenile reformatories, state industrial schools and asylums that were founded during the Progressive Era with the aim of reforming the nation’s wayward youth. The abuse that Robert Miller experienced in Iowa was not an isolated case; in Rothman’s investigation, he discovered pervasive abuses—including beatings that went unreported and unpunished, and mismanagement which led these institutions to accept unqualified men and women as staff members, rather than assigning the care of these at-risk children to talented, skilled professionals capable of using appropriate behavior-conditioning techniques.

Ineffective methods of discipline and management are still in use today in Eldora. From the State Training School for Boys’ beginning, it has never been properly staffed or funded; shortages of qualified professionals are more pervasive today than they were one hundred years ago. Although children are no longer beaten or forced to shovel coal on the pile as Robert Miller was, today “children suffering from mental disabilities are isolated in seclusion rooms” and—until recently 11 —“strapped to a table called ’the wrap’,” 12 a device resembling a gurney one might expect to see in a death chamber. These practices indicate a recurring theme which has plagued the school: an overriding desire for obedience at all costs.

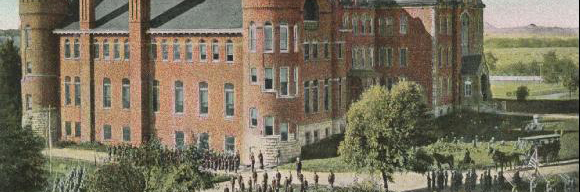

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2021-spring/grinnell_29961_OBJ.jpg)

Postcard image courtesy of the IAGenWebProject

The Industrial School’s Origins

The idea for a juvenile reformatory for boys originated with the Iowa State Teachers Association (ISTA), which in 1858 sent a letter to the state’s General Assembly to establish such an institution. In this letter, the ISTA asserted that “under present conditions, in spite of parents, school and churches, many children are truants, loafers, cigarette smokers, and petty gamblers … precocious sexual depravity, stimulated by social customs, impure literature, and vicious associations, is ruining thousands of promising youth.” 13 The school that served as the state’s answer to this state of affairs was first opened in 1868 in Iowa’s Lee County. At the time, such buildings were built in Iowa on leased land, but the state soon realized this was financially disadvantageous. Eventually it was decided that the school should be located close to the town of Eldora, Iowa. 14 Reflecting the spirit of the times, the new school was founded on Progressive principles, with the intention of reforming wayward youth through hard work and educational opportunity. The state legislature appropriated money for construction, which began 150 years ago.

The Industrial School for Boys instituted corporal punishment from its beginning to control boys there. Also, from the beginning, this policy was controversial. In June of 1875, only seven years after the school was founded, allegations were made that its first superintendent, Joseph McCarty, was mismanaging the institution’s finances and abusing the boys under his care. In response to these allegations, Iowa’s governor appointed an investigative committee which met from April through August of 1875. The school’s trustees later described the investigation as “one of the most severe ordeals that any state institution ever endured.” In the event, the investigation had barely begun before McCarty resigned. 15 Investigators eventually called over two hundred witnesses and ultimately concluded that “[b]olts, bars and corporal punishment may produce fear and command obedience; but never confidence, respect and love.” 16

Although the trustees said that they believed the children in the school had sustained abuse, this conclusion ultimately went nowhere. The board abrogated its authority, diluting the impact of its reports by stressing the previous abuse the children had suffered in their family homes. The Board stated: “Most of the boys sent to the reform school have dissolute parents if any… never have known the pleasure of being respected or trusted.” 17

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2021-spring/grinnell_29960_OBJ.png)

The campus of the current Iowa State Training School for Boys. Image courtesy of InmateAid

In the end, McCarty’s resignation was not a solution to the school’s problems, and in fact was clouded by suspicious leniency and excuse-making from officials. Legislators came to visit the reform school on a fact-finding mission after McCarty’s resignation and met with the new superintendent, Reverend Charles Johnson, who was brought in from the state of Michigan. When Reverend Johnson arrived, he found the school to be in disorder arising from the previous summer’s investigation. 18 In their reports, though the legislators repeatedly called for the children to be treated nicely, they defended the practice of punishing them harshly. One state legislator said in his report that “The law of kindness prevails, and punishment is resorted to only when all other means fail to secure obedience to the rules.” 19

What these words do not convey is what was defined by the word “punishment.” Many different forms of discipline were used. For example, when the Dean of Boys administered corporal punishment, he used a leather strap four inches wide, a quarter-inch thick, and two feet long. 20 There is no comprehensive list of the forms of punishment employed, but we do have the legislative and board of trustee’s reports that share the same conclusions about physical punishment—that is, that it should be kept to a minimum.

In their aggregate, these practices indicated that an overriding desire for obedience at all costs was permitted to win out over kindness. Public documents 21 show that the change in the institution’s leadership after McCarty’s resignation did not also mean a repudiation of violence against the boys. The documentary evidence suggests that the Board of Trustees, and then later the Board of Control that took over regulation of the school in 1900, were either complicit in the ongoing use of physical punishment or else lying about it.

The Board of Control seems often to have had corporal punishment on its collective mind, and to have been conflicted about it. In talking about the methods being used to correct the children at the Iowa Industrial School, one board member stated, “The Board does not believe that the application of the lash, depriving of food, or the riveting of iron bars on the limbs of pupils has a tendency to improve their condition or assist in their reformation, and requested those methods of punishments should be discontinued.” 22 However, in the very same report the superintendent of the school asserts that “Very firm and even rigid discipline at times is necessary for this class of young men.” This disparity—between the philosophical stand taken by the school’s controlling board and the disciplinary practices advocated by the superintendent—raises the question of who truly controlled the school. The Board of Control’s public declaration that it was against corporal punishment may have appeased those who thought critically of the school, but in the end the school continued to use physical punishment to enforce discipline until 1961. 23

While it might seem reasonable to expect that Robert Miller’s murder provoked major changes in the operation of the State Training School, the state’s response to the tragedy was to build a $250,000 security unit to house students labeled as “unmanageables.” 24 The implication is that, as far as the state was concerned, Robert Miller’s unmanageable behavior was to blame for his death, not the adults who beat him and then denied him medical attention. This is emblematic of the sort of entrenched thinking that came to define the school. Twenty-three years after Miller’s murder, an administrator at the school admitted that “Punishments were sometimes deadly, severe and administered out of hate instead of love; boys were sometimes exploited out of perverse needs of grown-up misfits; terrible crimes were committed in self-righteous autocracy. It must be kept in mind, although it excuses nothing, that shocking things have occurred in every human institution, including the church.” 25 In other words, rather than accepting responsibility for the actions of those in charge—which would call the whole rehabilitative system into question—the school deflects blame onto everyone else, including religious institutions.

The Struggle for Funding

The State of Iowa paid a flat per diem for each child sent to the State Training School for Boys. The school then used the boys as free labor to work the farm, and the farm products were then sold on the commodities market. The profits from the farm were used to cover operating costs at the school. Thus, receiving a per diem created an incentive for the institution to keep children longer and encouraged the commitment of children who had not committed a crime, but (for example) were merely homeless vagabonds. A review of multiple historical documents indicates that over a thirty-year period, vagrants and unmanageable teenagers were sent to the school at increasingly larger numbers than juvenile delinquents. 26 In addition, the institution used a badge system that determined when a student had earned his way out. By 1895, the average stay at the school was three and a half years. Thus, a homeless child could end up staying at the school the same amount of time as a juvenile delinquent. 27

From its beginning, the State Training School for Boys accepted children who did not have a criminal record. From 1873-1897, children who were merely vagrants or homeless made up the majority of those committed to the school. For example, in the first two years after the school opened, 65 percent of children sent there were juvenile delinquents, while 35 percent were unmanageable or vagabonds. 28

‘In Our Care’ is a 1952 documentary made by WOI TV that offers a rosy view of the philosophy and aims of the Iowa Training School for Boys. To link to the documentary on YouTube, click on the image above

By 1897, though, the percentages had flipped; 60 percent of the children sent to the Iowa Training School were not criminals, nor did they have a criminal record. 29 Additionally, during a two-year period from 1885-1887, 71 percent of the children committed to the school ranged in age from eight to fourteen. 30 Being vagrant, unmanageable, young, or homeless were risky occupations for kids in the State of Iowa during this time. The change in these statistics demonstrates that the institution and the State of Iowa were failing at-risk children. It is possible to make the inference that the administration of the school needed to fill empty beds with warm bodies, and it did not matter that over 65 percent of the boys sent there were not criminals. The school’s operating costs were lowered because it exploited children’s labor.

In a short history of the school, titled “The Industrial School for Boys at Eldora Iowa” 31 the Hon. W. J. Moir, an original member of the school’s board of trustees, used a table on the last page to compare 30 reform schools in America. Moir’s table showed that Iowa’s expenditure on the school’s students of $96.00 per student per year—eight dollars a month—was by far the lowest of the institutions listed. One might initially assume that the low per diem stemmed from Iowa’s status as a rural state with a lower cost of living. However, when Iowa’s rate is compared with the rates in the states surrounding it—which are also predominantly rural—it becomes clear that every state that has a border touching Iowa spent more money per student. For example, Nebraska spent $172.00 per student per year more; Illinois spent $50.00 more, and Wisconsin $110.00. 32 To offset the low per diem, the State Training School for Boys needed another way to generate revenue and one of its earliest superintendents thought he had an answer.

B. J. Miles was the school’s fourth superintendent, serving for over twenty years in this post. In 1883, very early in his tenure, Mr. Miles wrote a one-page article in a book called Industrial Training of Children in Houses of Refuge and other Reformatory Schools. 33 Mr. Miles wrote that “public opinion will not tolerate any enterprise, in an institution of this kind, that will not [bring] revenue [into] the institution. Our farm of 500 acres is revenue, and many boys are fitted for farm hands on it….” 34 Research suggests that Mr. Miles’s system of free child labor was successful. By 1885, the State Training School for Boys was producing a surplus of commodities. In a two-year period alone, 1885-1886, the school’s farm produced 25,000 pounds of beef, 25,000 pounds of pork, 250 bushels of white beans, 2,100 bushels of potatoes, 36,000 gallons of milk, and $5,000 worth of vegetables. 35 In 1886, a state legislator visiting the reform school suggested “[Forty] cows should be kept for the boys so they can have butter on their bread and milk once a day,” 36 apparently unaware that the farm’s produce was being sold for support and upkeep of the school.

When considered together, this evidence strongly suggests that three decades after the school’s foundation, its goal was no longer reform. The school—originally begun as an institution dedicated to helping wayward youth, and specifically those convicted of crimes—had been transformed into an institution that accepted vagrants, truants, and unmanageable teenagers whom adults felt needed to be corrected, to ensure a viable workforce capable of providing cheap labor.

In 1898, the Iowa Board of Control was tasked with overseeing the school, a responsibility which before this time rested with the Board of Trustees. The Iowa Board of Control immediately noted major deficiencies at both the State Training School for Boys and the State Training School for Girls and reported its findings to the Iowa Legislature. The Board wrote: “The condition of no other institution in the state has proved so unsatisfactory to the Board as that of the two industrial schools… there are confined in these schools young men and young women whose presence is pernicious in the extreme and who should not be allowed to mingle among, and contaminate by their presence, mere children as yet unacquainted with crime.” Despite the strong wording in the Board’s report, Iowa state legislators did nothing to remedy this problem, and as we will see from future difficulties, failed to correct other issues facing the institution. Instead, the school was permitted to continue morphing into a catch-all institution which housed teenagers and children who had any issue that adults felt must be corrected.

Over two decades later, conditions at the school still had not improved. In yet another report, issued in 1924, District Judge S.A. Clock wrote that the school was only “interested in getting rid of the boys as soon as [its plan]… will allow… in other words they are forced by the state to adopt plans that consider principally what the boys cost and handle them as cheaply as possible.” Judge Clock went on to call the state to task for its lack of concern for preparing boys at the school for gainful employment when they left. But while nothing would change at the school to make it into a true vocational training school, the state of Iowa did have another solution in mind.

Military Discipline or Training for a Trade?

It was in the early 1880s that the school began a transition from being an industrial school into a military academy. Cost of operation was one reason: running a military academy was dirt cheap compared to running the school according to its original Progressive principles and purpose. Militarism also taught submission to institutional rules and obedience to military rules and regulations. Because military discipline demands the ability to follow orders without thinking critically, inducing children to follow military instructions made them more docile and compliant. In 1897, Dr. W. E. Whitney, the school physician, sent a report 39 to the Iowa legislature which bolstered the opinion that military training was good for children. Dr. Whitney said, “[w]e have been remarkably free from casualties and accidents. This is largely to be accounted for by the introduction of military tactics and discipline.” Thirty years after the school opened, the only jobs available to the children there were manual labor. Examples include farming, playing an instrument, and school maintenance. These types of jobs helped the institution and kept the boys busy throughout the day and parts of the night, but when it came time to leave the school, these boys had not been properly prepared to gain meaningful employment or adjust to a changing society.

‘The wrap,’ a restraint device now outlawed at the Iowa State Training School for Boys, but used for many years to discipline ‘unmanageable’ youngsters. Photo courtesy of Disability Rights Iowa

In 1905, John Cownie, a Board of Control member, would try to help some of the boys leaving the school to find work. He would ask them: “What type of work are you fitted for, the answer would be, well I have worked in the laundry, or I have played in the band.” 40 When young boys sent to the training school had earned their freedom, a vast majority did not have the tools to succeed because they had not been taught a skill that would enable them to find gainful employment. Cownie recommended the school change both its focus and its name: “I believe the time has come when the industrial school for boys… should become a thing of the past,” Cownie said, “and in its place let us have the Iowa State Military Academy.” 41 Cownie went on to say that “Military tactics is one of the leading branches taught, the discipline and drill this offered prove [to be of] great value to the boys.” 42 Was this change instituted because military training made it easier to control the boys, or because military training afforded the boys a value—that is, it prepared them for war? In fact, during the Spanish American War, fifty boys trained in the military companies at the school joined the army, and twelve went into the military band. Cownie could not find a boy a job playing the trombone outside of the military, yet during wartime, jobs for band members became readily available.

The Governor of Iowa appointed Otto Von Krog superintendent of the Iowa Training School in 1922. After he took control, the Iowa Training School abandoned the pretense of running a normal school. 43 Von Krog said “The properly disciplined boy is dependable, willing, prompt and consistent.” 44 Von Krog used militarism as a tool to exert control over the entire school, and he immediately began a program to expand military training. Under Von Krog, military drill became an everyday exercise. In fact, Von Krog’s mantra was “Discipline through Militarism.” He also expanded athletics and rewarded the best athletes with extra food and extra merits, which could substantially reduce a boy’s stay in the institution. For twenty years under Von Krog’s control, military drills and athletics dominated the school.

What’s Happening at Eldora Today?

Today, the State Training School in Eldora, Iowa, faces challenges it is unqualified to properly handle. Disability Iowa issued a report, titled “Unlicensed and Unlawful” 45 which detailed the failures at the school. Specifically, the lawsuit alleges psychiatric medications are administered to students and used as a chemical straight jacket. 46 Moreover, the school uses restraints and isolation cells as a form of discipline and treatment for children suffering from mental disabilities. 47 In one instance, a suicidal boy from Des Moines was placed in solitary confinement 53 times, for a total of 1,000 hours, during a seven-month period in 2017. 48 This mentally distraught child exhibited suicidal thoughts rather than behavioral problems.

The State Training School for Boys employs unlicensed psychological professionals. In its suit, Disability Iowa alleged the State Training School for Boys uses “a full-time counselor who is referred to as a psychologist, even though he is not licensed as one.” 49 However, even someone without a medical degree could understand why isolating a suicidal teenager for 1,000 hours over a seven-month period would be detrimental. The question must be asked, then: why didn’t those in charge recognize the danger? In 2017, Mark Day, the superintendent of The State Training School for Boys, strenuously defended the school’s practice, saying boys were “sent… to us because [other institutions] could not manage their behaviors…we take kids they can’t handle.” 50 It is striking that this comment is so similar in tone and substance to one made by B. J. Miles, the superintendent in 1887: “[V]ery firm and rigid discipline at times is necessary for this class of young men.” 51 Labeling children as deviant criminals or saying they are out of control allows the state to abuse them without suffering any blowback. The state admits that it does not know how to handle these cases, so it locks the problem out of sight. The State of Iowa pretends to solve this problem by putting children in “unmanageable” cells, using isolation to further punish them.

Traditionally, when children are physically abused, society moves quickly to make sure the mistreatment stops, particularly when the victims are young children with mental disabilities. Society and government share the responsibility of ensuring children are not abused. However, in this instance, instead of directing an investigation into the abuses reported in 2017, Jerry Foxhoven, the Director of Iowa’s Department of Human Services (which managed the State Training School at the time) insisted that “He [saw] no reason to order a special investigation of the Eldora boys school.” 52 In fact, on August 8, 2017, a day before Foxhoven made this statement, The Des Moines Register ran an editorial 53 which characterized the school’s residents as “violent offenders” rather than as children needing psychological help, giving the school and Department of Human Services cover without conducting any independent investigation of Foxhoven’s statements. Also, Foxhoven defended the use of the wrap. 54 Foxhoven readily admitted that the device was “a scary thing to look at,” but apparently did not find it terrifying enough to outlaw its use.

Since the time the editorial ran, the tone of public discussion of the school has changed from one of outrage to apathy. Now, government agencies tasked with protecting children are openly advocating the use of isolation to deal with those with mental disabilities. Republicans in the Iowa Legislature tried to resolve the Disability Rights Iowa lawsuit by removing from the Iowa code references to “treatment” offered at the State Training School and to the “diagnosis and evaluation center.” If this language had been removed, then the state training school at Eldora would not have had to offer treatment to students. However, Democrats in the House adopted an amendment which restored references to treatment and the bill passed the Iowa House 59-38. 55 The bill also contained language that advocated “rehabilitation through disciplined confinement.” 56 In his book, Conscience and Convenience: The Asylum and Its Alternative in Progressive America, David Rothman diagnosed the problems with institutions similar to Eldora, namely that discipline saturated every characteristic of the schools. Rothman wrote: “Every sanction had to have its back-up sanction (until punishment degenerated into cruelty), because institutional order had to be maintained, and because one more threat always had to be available for the inmate who insisted on challenging institutional boundaries.” 57 That is, discipline had to trump compassion and empathy to ensure that order was maintained, and the system worked. Professionals were unable to manage children, so the institution worked with Republicans in the Iowa legislature to change the law, allowing the mistreatment of children—by locking them in cells and strapping them in the “wrap”—to continue.

Conclusion

In two works published in 2003, Conscience and Convenience 58 by David Rothman and A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of The Progressive Movement in America 59 by Michael McGerr, the authors acknowledge that Progressive Era reforms like asylums and juvenile reformatories failed to properly rehabilitate children. Robert Miller’s murder shocked the conscience of society, even making a front-page headline in the New York Times. However, those responsible for his murder escaped punishment and went on with their lives as if nothing happened. The details of Miller’s murder seventy-three years ago may have lost some of their urgency, but the fact that those responsible for his murder escaped punishment highlights a pattern of gross neglect and exploitation of children by the school.

What is at stake here is the care given to children with mental disabilities. The “unmanageables” unit built after Miller’s murder—essentially a jail inside of a facility created to “help” children—betrays a misapprehension concerning the way children with mental disabilities ought to be cared for. Rothman insists that the core of the problem is “the incompatibility of custody and rehabilitation, of guarding and helping.” 60 Nevertheless, the Director of the Department of Human Services, Jerry Foxhoven, and Mark Day, Superintendent of the state training school, in company with at least fifty-eight Republican State Representatives, believe in “rehabilitation through disciplined confinement.” 61 Despite the fact that rehabilitation through coercion by force did not work 150 years ago, nor 73 years ago when Robert Miller was murdered, it is still being used today at Iowa’s State Training School for Boys in Eldora. Seemingly heedless of the policy’s ineffectiveness, the state of Iowa will continue this absurd approach to rehabilitating children, and in another hundred years another history student will find these reports, and write another paper, about another tragedy at this school.

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2021-spring/grinnell_29962_OBJ.jpg)

‘I have worked in the laundry, or I have played in the band.’ The Iowa Industrial School for Boys’ Band in an undated photograph, courtesy of Iowa’s Town Bands, 1890-1930.

In 1876, after the investigation that ended the first superintendent’s career, a report was issued by the Board of Trustees that insisted “Bolts, bars and corporal punishment may produce fear and command obedience, but never confidence, respect and love.” 62 The “bolts, bars and corporal punishment” that were acceptable in the past may have been superseded by seclusion cells and the use of the wrap, but these methods of discipline are also antiquated, and continue to do more harm than good. Forced reform is not change; it is simply a way in which adults force young children to behave in ways they, the adults, find acceptable. Although the human soul abhors oppression, these methods will probably continue, because it is easy to lock away and tie down what the state cannot control or even understand. Many in Iowa’s state government and those in control at the school would probably disagree. They would say they are only trying to help these rebellious youths. In reply, I would ask: why, then, does this debate about how to treat children continue, one hundred and fifty years after the State Training School for Boys opened? To put it plainly, the system failed one hundred and fifty years ago and it is failing today, not because the structure of the school cannot be fixed, but because coercion and rehabilitation through force are the only models of reform that these institutions know. Bolts, bars and corporal punishment may have now been replaced by seclusion cells and the wrap, but that is not because these methods of rehabilitation are more effective. It is because they are convenient.

The time has come to try something different. Instead of treating children as adults who are in prison, we should treat them as children who have made mistakes. In settings such as Iowa’s State Training School for Boys, children need compassion and love because they may never have known that type of kindness in their lives.

The State Training School for Boys does not have licensed psychologists on staff. Full-time counselors who lack doctorates in psychology and would be prohibited from practicing psychology in public are nonetheless referred to as psychologists. 63 Instead of hiring people who, however well-intentioned, do not have the skills which caring for these children requires, the state must hire licensed professionals who are specifically trained to treat children suffering from trauma. Additionally, under current laws, the State Training School for Boys is not required to have a state license, meaning it is not subject to regular inspection by the Iowa Department of Inspections and Appeals. 64 The school should be licensed, and the State of Iowa’s Department of Inspections and Appeals should conduct regular inspections. These children are not convicted felons under the law, but have been adjudicated to be delinquents, and will not have felonies on their records when they become adults. Therefore, under no circumstances should institutional control be given over to the Department of Corrections.

Next, the school must shake off its outdated discipline model and usher in a progressive approach that finally, once and for all, ensures that kindness prevails over bolts and bars or isolation and wraps. A new regime must be instituted which offers meaningful vocational programs, and which allows children more freedom of movement, on a campus dedicated to rehabilitation through education. This will restore the school to its intended purpose—that is, to be an institution which teaches and reforms, not a prison that harms mental health.

The school’s history shows that punishments, when required, have been “administered out of hate instead of love,” and found that boys were being exploited to satisfy the needs of grownups, and were victims of crimes committed in the name of “self-righteous autocracy.” 65 These words mean something because they convey the significance of these institutions’ mindset. When run as this report has detailed, institutions like the State School for Boys do more harm than good. The expediency of running an institution this way has ensured that these practices have continued for one hundred and fifty years.

David Rothman says of institutions such as the State Training School for Boys that “Every sanction had to have its back-up sanction (until punishment degenerated into cruelty), because institutional order had to be maintained, because one more threat always had to be available for the inmate who insisted on challenging institutional boundaries.” 66 As long as this remains the modus operandi of institutions like the State School for Boys, then one day, maybe soon, another Robert Miller story will emerge to shock the conscience of humanity yet again.

Postscript by the author

I was twelve years old when I first arrived at the State Training School for Boys, and thirteen when I left. To say I was scared would not do my fear justice: I was terrified. I arrived at Eldora a young boy and left with more knowledge about crime and hustling than a young boy should have. While at Eldora I experienced abuse and spent over 1,200 hours in isolation, 1,000 of those hours within six months of arriving there. Spending 1,200 hours in segregation at such a young age created an exoskeleton that shaped my future. I learned at a very young age to distrust those in authority and realized nobody but me could get me back home.

I learned that adults can be petty and cruel. I stood 5"2" and weighed 110 pounds, which made me extremely vulnerable, because I had no way to defend myself physically. I lacked the mental toughness to shield my young mind from the relentless onslaught of older boys’ cutting remarks. I spent days and weeks crying, wondering why my mom could not come to take me home. The administration claimed I suffered from “separation anxiety” and prescribed me two psychiatric medications. In fact, the only problem I suffered from was being a twelve-year-old child who missed his mom, dad, brothers and little sister. I had never been arrested before being sent to Eldora. Nevertheless, breaking the law got me sent away for over two years.

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2021-spring/grinnell_29964_OBJ.jpg)

The Iowa Industrial School for Boys as it looked during its early history. Postcard Dated 1910, courtesy of Iowa’s Town Bands

I often think about Eldora, and about how much that place shaped my future. Eldora made me into a young person distrustful of authorities, who always felt hyper-vigilant, afraid of being alone, and who always pursued affection. When I first heard about Robert Miller’s murder, his story gripped me and wouldn’t let me go. I have been waiting to write this story for the last thirty-two years of my life, and when the opportunity presented itself, it took me almost two years to complete it. More importantly though, maybe this cathartic exercise will help me purge bad memories, and maybe, just maybe, to heal old wounds. As I finished writing this paper, I had tears in my eyes, yet my tears are not for me; my tears are for the Robert Millers and other children who suffered before me, and for those children yet to arrive at the State Training School at Eldora. I have been incarcerated for a total of seventeen years in the State of Iowa and there were other graduates of the State Training School in prison with me. That institution abuses young children who grow up with significant behavioral problems.

The State Training School began as an idea; one which Progressives hoped would change children’s lives, to make their lives better. This idea morphed into something contradictory to its intended purpose, producing aggression, hatred, and fear, not love, kindness and respect. Ultimately, children suffering from psychological disabilities may grow up hating authorities, and the aggression they were taught as young children may manifest itself into adulthood.

1 John Farmer, employee of the State Training School for Boys. Interview conducted at the school by Grinnell College student Emma Cibula, April 24, 2017.

2 John Schrock, interviewed by the author at Newton Correctional Facility. August 31, 2018. Mr. Schrock is an Amish farmer who has worked with draft horses his entire life. Mr. Schrock said that a ‘harness tug’ is a heavy strap, two-and-a-half inches wide and half-an-inch thick, that is used in harnessing a horse to a wagon. This strap passes over the horse and hooks to the singletree of the wagon. Schrock also said that a chain or metal piece 12-14 inches in length connects to this strap and it weighs about five pounds. It was this metal piece, in the form of a rod, that was used to beat Robert Miller to death. He insisted that in 1945 the harness tug would have been made entirely of metal and thick heavy leather, rather than being made from nylon, which is more common today.

3 ‘Hunt Escaped Boys at $10 A Head in Iowa.’ The New York Times, August 31, 1945

4 Fred Tully, Larry Morris, Thomas Reiber, Donald Pranger, Anthony P. Travisono, Carle F. O’Neil. The Echo Iowa Training School for Boys: A 100-year history of the State Training School for Boys, 1868-1968. Eldora, Iowa: State Training School for Boys, 1968.

5 Ibid., p. 4.

6 ‘Jury Indicts Five Eldora Officials.’ The Daily Iowan, September 23, 1945.

7 Ibid

8 Ibid

9 Michael McGerr, A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of The Progressive Movement in America. New York: Free Press, 2003, p.xiv.

10 David J. Rothman, Conscience and Convenience: The Asylum and Its Alternative in Progressive America, Revised Edition. New York: Transaction Publishers, 2003, p.282.

11 Jason Clayworth, ‘Judge Orders Halt to Use of Restraint Device at Iowa Detention Facility for Boys; Calls It ‘Torture.’’ Des Moines Register, March 31, 2020.

12 Tony Leys, “DHS Leader Sees No Need to Investigate Eldora Boys School after Mistreatment Complaint.” The Des Moines Register, August 8, 2017.

13 Keach Johnson, “Roots of Modernization: Educational Reform in Iowa at the Turn of the Century,” The Annals of Iowa, Volume 50, Number 8, Spring 1991, State Historical Society of Iowa, p.892-918.

14 Tully, et. al., 1968, p.11

15 J. A. Parvin, Eleazar Andrews, M. A. Dashieli, W. L. Vestal and Thomas Corkhill. Fourth Biennial Report of the Board of Trustees of the Iowa Reform School. Des Moines: R. P. Clarkson, State Printer, 1875, 1876.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 E. G. Miller, John McCartney, W. H. Reed, ‘Report of the Joint Committee to Visit State Reform Schools,’ Iowa Legislative Documents, 1876, Vol 111. Publisher unknown, 1876.

20 Frederick Lovell Bixby, William B. Cox, Handbook of American Institutions for Delinquent Juveniles New York: The Osborne Association Inc., 1938.

21 ‘Report of Board of Control’ in Vol VI of the Iowa Legislative Documents, submitted to the Twenty Eighth Gen-eral Assembly of the State of Iowa. Des Moines: F. R. Conway, State Publisher, 1900. The Board of Con-trol took over from the Board of Trustees, and this report came out of the Board of Control’s first visit. The visit exposed major problems with the school, yet this led to very little to change over the practices of previous administrations. That is, the board failed to change the policies, which could have stopped corporal punishment.

22 Ibid

23 Tully, et. al., 1968.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Parvin, et. al., 1875, 1876; C. C. Cory, ‘Eighth Biennial Report of the Girls School,’ Append ix. The Report of the Superintendent of the Girls Department, publisher unknown, 1887; B. J. Miles, Tenth Biennial Report of the Superintendent of the Boys Department. Des Moines: F. R. Conaway, State Publisher, 1887; B. J. Miles. Fifteenth Biennial Report of the Superintendent of the Boys Department. Des Moines: F. R. Conaway, State Publisher, 1897.

27 Tully, et. al., 1968, p. 20

28 Parvin, et. al., 1875, 1876.

29 B. J. Miles. Fifteenth Biennial Report of the Superintendent of the Boys Department. Des Moines: F. R. Conaway, State Publisher, 1897. These reports were published every two years, and detailed what children had been sentenced to the school for, as well as where and how the money was being spent.

30 Ibid.

31 Hon. W. J. Moir, “The Industrial School for Boys at Eldora.” Bulletin of the Iowa Board of Control. Publisher unknown, 1898.

32 Ibid.

33 B. J. Miles, in Industrial Training of Children in Houses of Refuge and other Reformatory Schools, by William Pryor Letchworth. 1883.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 Tully et. al., 1968. p.18.

37 ‘Report of Board of Control’ in Vol VI of the Iowa Legislative Documents, submitted to the Twenty Eighth Gen-eral Assembly of the State of Iowa. Des Moines: F. R. Conway, 1900.

38 S. A. Clock, Judge of the District Court at Hampton. ’tate Institutions—Support Provided and Service Expecte d .’ State of Iowa Bulletin of State Institutions, 1924, pps. 248-251, 216-222.

39 Miles, 1897.

40 John Cownie, ‘Our Industrial Schools.’ Bulletin of State lnstitutions, Vol. 7, publisher unknown, 1905, p. 444.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 Tully, et. al., 1968, p.48.

44 Ibid., p.42.

45 Leys, August 8, 2017.

46 Barbara Rodriguez. ‘Lawsuit: Iowa School for Juvenile Offenders Misusing Drugs,’ Across Iowa, Associated Press, November 27, 2017.) https://patch.com/iowa/across-ia/lawsuit-iowa-school-juvenile-offend-ers-misusing-drugs

47 Clark Kaufmann, ‘Iowa State Officials Sued over Isolation Cells at Boys’ School.’ The Des Moines Register, November 27, 2017.

48 Ibid.

49 Tony Leys, ‘State School Accused of Using Isolation, Restraints on Troubled Boys Who Need Treatment.’ The Des Moines Register, August 7, 2017.

50 Ibid.

51 B. J. Miles, Tenth Biennial Report of the Superintendent of the Boys Department. Des Moines: F. R. Conaway, State Publisher, 1887.

52 Leys, August 8, 2017.

53 Editorial board, ‘Don’t Leap to Judgement on State Boys’ School,’ The Des Moines Register, August 8, 2017.

54 Leys, August 8, 2017.

55 Brianne Pfannenstiel, ‘Democrats Push Back on Changes to Eldora Boys’ Training School.’ The Des Moines Register, March 7, 2018

56 Ibid.

57 Rothman, 2003.

58 Ibid.

59 McGerr, 2003.

60 Rothman, 2003, pg. 282.

61 Pfannestiel, 2018.

62 Parvin, et. al., 1875, 1876

63 Leys, August 7, 2017.

64 Ibid.

65 Tully, et. al., 1968

66 Rothman, 2003, p.283.