Moving to Iowa was a culture shock. Until my first year at Grinnell, I’d spent my entire life living in Philadelphia. Even though a lot of that time was spent in the Philadelphia suburbs, the area was nothing like Iowa. In Iowa, everything seemed different: the large and empty fields, the houses, the clear night sky. At home, any fields as large as those I’ve seen in Iowa were either used for parks or converted into golf courses. The tract housing surrounding Grinnell doesn’t resemble the type of home architecture I would frequently see back in Philadelphia. Regarding the night sky, at home I’d be lucky to see even a few stars, while here, I see more stars than I could ever count.

I also find Grinnell quite different socially. To start, I found myself knowing no one and had to make a new social circle for myself. Through this process, I was able to learn more about many different people. Take for example one of my good friends. While growing up outside of Atlanta, in a deeply religious family, he was not able to express himself as who he really is. After coming to Grinnell, he came out as gay and has been able to find himself in ways he never could have outside of Grinnell. Originally, stories like these and others from different friends moved me to create poems about how Grinnell has changed people. But while Grinnell College is a wonderful place in many ways, it doesn’t do a great job at representing the prairie region. The College is filled with students and faculty from all over the world. This creates a social environment vastly different from one you’d find a few miles down the road in any direction. Although a lot of my time has been spent within the College, I have spent some time outside its social environment. Whenever I’ve gone to a restaurant or store in Iowa, the norm is for people to behave with kindness. People can be kind in Philadelphia too, but that kindess isn’t a given as it is in Iowa.

While my friends and I have been able to become comfortable with the Iowa norm, and even to express ourselves in ways we never could have outside of Grinnell, I wouldn’t say that we have made ourselves at home here. In truth, I’ve rarely thought about the prairie region surrounding me—something that working as an Associate Editor for Rootstalk has forced me to reconsider.

What does it take to find a sense of home in the prairie region? To answer this question, I decided to talk to four individuals who moved to Grinnell from outside the prairie region to take jobs at Grinnell College and, in the process, discovered a sense of home here. I asked them how they found a connection to this place. I asked how long that took, what the ways were in which they discovered this new sense of belonging, and whether this sense was, in their experience, unique to the prairie? Lastly, I asked if, after living in region for years, they considered themselves to be “locals.”

White-tailed Deer at the Pleasant Grove Land Corporation. Photo courtesy of Sandy Moffett

In order to gain these insights, I interviewed Chris Hunter (CH), Sigmund Barber (SB), Betty Moffett (BM), and Sandy Moffett (SM). All four have now spent over half of their lives on the prairie, and have now retired in Grinnell. Here’s what they said:

Rootstalk: Where are you from originally and what is it like there?

CH: I grew up in northern New Jersey. Northern New Jersey is sort of a suburb of New York City. You go from one town to the next and you have no idea you left one and entered another except maybe the houses are more expensive. The town I grew up in was just like that: one of the middle-class towns right next to the really rich ones. Coming to Grinnell itself was a bit of a shock. I realized, “Wait, I know exactly where the end of the town is here because there’s a cornfield there.” Some people got really upset by that, but I liked it. I appreciated knowing where things ended.

SB: [I was born in] Austria, but I’ve lived in many places. My stepfather was in the military, so I’ve lived in California, Kentucky, Colorado, but mainly Germany. When I was eighteen, I came to the United States for college and lived in Upstate New York for ten years before moving here. I enjoyed moving around. It wasn’t difficult for me. I never found it difficult to make friends so I would make new friends wherever I was and could adjust very easily. I enjoyed all the places except for Kentucky. With all the moving and the culture of the military, I had never encountered racism. It really bothered me. I wanted to go play with some new friends I made, and I was told I couldn’t. I couldn’t understand why this was the way it was.

SM: North Carolina. It’s a great state. It has the ocean and the mountains. At that particular time, it was quite liberal, so we enjoyed the political atmosphere when we lived in Chapel Hill for a while. When we came here, we didn’t want to leave North Carolina. I didn’t want to come here, and I didn’t want to stay here. My idea was to come here until I could find a comparable job in North Carolina.

BM: When we first got here, I thought I was going to fall off the earth because all the trees were gone. But now when we go back to North Carolina I feel a little claustrophobic. I’ll always love North Carolina, but do I miss it anymore? No.

Rough blazing star (Liatris aspera) at the Pleasant Grove Land Corporation. Photo courtesy of Sandy Moffett

Rootstalk: What did you first notice about the prairie countryside when you moved?

CH: We didn’t travel out of town very much. We did go to Des Moines some, and I remember that one of the things that struck both my wife and me was that you drive to Des Moines or Iowa City and there’s nothing between here and there but fields. At first, I thought that was really ugly, especially in the fall, but I’ve since grown to appreciate the variations of brown in the countryside. Living on the prairie was not my life before then. It is now. The rolling countryside was something I really got to like. I was just noticing the colors when we came into town the other day and the variations in slight tinting of green now, which I didn’t notice. Back home we had noticed it in the trees, but here it’s somehow more subtle.

SB: Well, it was definitely different in many respects to what I had experienced before. I spent a lot of my first month when we arrived in August sitting on the front porch of the house we rented. When storms came through, which they did in August, I was fascinated by the openness of the sky and the lightning storms. The power of nature, which had always interested me, was in full display. This was something I’d never experienced before. I mean we had lived in rural areas, but nothing with the sky this big where you could observe the things that were going on. I was fascinated just sitting there watching the lightning go from cloud to cloud. It was the same thing for me when we had tornado warnings. It was hard for me to go to the basement because I wanted to see it, which was not a good idea.

SM: We lived in the country and almost immediately became aware of the landscape. It was different. The fields were much more ragged than they are now. There were bushes in the fence rows and the gullies. A lot of those have disappeared with new farming practices. But I became aware of the landscape. I realized it was a really rich landscape with lots of wildlife and lots of interesting things. There were probably more birds and animals here than there were in North Carolina even with all those woods and trees. It was a little-by-little incremental thing.

BM: It looked ragged at first. My father always thought that the prairie and anything that looked like the prairie was weeds. He came here a few times. He liked the fact that the corn grew as high as it did. One day we were walking, and he looked out across the prairie. That day, the wind was blowing, and he said, ‘It looks like an animal’s hide.’ It’s rich and full of deep colors. Also, we came from North Carolina in 1971, and then integration and segregation were a big deal. One of the things that was amazing to us when we came here was that it wasn’t present. I remember going to a gathering and one of the women asked me if coming from the South I was concerned about integration. I told her no, and then she let me know that segregation wouldn’t be a problem here. Coming from the South, being able to see integration and a lack of segregation was astonishing. Something else I noticed is that people were very kind. It wasn’t a Southern kind, not, ‘oh come on over to our house right now and I’ll give you a big hug.’ Rather, it was genuinely kind. One time I had the flu, and a woman from across the street brought me ginger ale and apple sauce. I think it saved my life. This woman didn’t know me, but she helped me anyway.

St. Paul’s Episcopal church. Photo by Ian MacMoran

Rootstalk: In what ways did you integrate yourselves into the community?

CH: My wife was strongly committed to public education. I got involved in MICA (Mid-Iowa Community Action, a local agency that works with families in need). I was on the board for a long time. And now I’m on the Grinnell Area Arts Council. We’re a part of the community so we wanted to do things. College faculty who live here get asked a lot to get involved. But I also feel a commitment. That was different. I hadn’t felt a commitment to where I lived before. I lived in the town. That was it. I didn’t even go to school in that town. I didn’t feel a connection [in New Jersey], and I had one now. After a while we branched out and we got to know people partly through church. We joined in part just to become more involved in the community. Some of those friends are still friends of mine. Those are the batches of friends we still have after all these years. I’m not even a religious person, but Grinnell is [a religious community]. We knew that one of the strong ways of connecting to the community was through the social world of the church. We picked St. Paul’s Episcopal Churchbecause it’s politically more palatable for us. It was initially in large part because of our kids. We wanted our kids to have the experience of being a part of the community and be seen as normal. Back then and maybe even now it was normal to be a part of a church. We got to know great people, so that was really important. But it wasn’t faith-based motivation on my part.

SB: I can’t remember how quickly it happened, but I became very active in the community and still am. I developed friendships with people not associated with the College. Eventually I was asked to be on various committees and boards and things like that. I had no problems assimilating into the community, which was a source of immense satisfaction to me. I became part of the community but not just the College community, but also the Grinnell community. I was able to navigate between these two cultures. Many of my College friends live in the community of Grinnell but are not an integral part of the community. They never went outside of the College culture, which is too bad because there’s something lacking there. At the time in Grinnell, there were restaurants, but not as many as there are now. Because of this, our group created an international dinner club. We would meet once a month and focus on one particular culture. We would drive to Des Moines and get authentic ingredients.

There also used to be something called Town and Gown, which was a fundraising effort between the College and the community. I was involved with that. My wife and I chaired the organization one year. We also began having kids in our second year in Grinnell, so we became involved in the schools and in parents’ organizations in the town. I’m still a member of some organizations that are a grouping of College people and towns people. I was later asked to be on the hospital board and eventually become more involved in community theater. I acted in some plays and musicals, and eventually got into directing.

SM: [Grinnell anthropology professor] Doug Caulkins and I had an idea—kind of a dream of preserving some land. By that time, I was deeply into prairie restoration. Doug and I sat down, and we wrote a letter. Doug worked out the financial business, the cash flow, how much we’d have to invest and how we’d pay for it over the years. We circulated this letter around campus to some faculty and a few people in town. In the letter we asked if anyone was interested in this. If we could get 10 investors, we could do it. We ended up getting nine families that were willing to invest. Initially we were going to buy 720 acres of land in Mahaska County, but planned to sell back 80 acres so we could do it with the nine families. We bought it and the rest is history. We immediately began planting prairie, enhancing prairie, and burning to get rid of invasive species. This is an ongoing thing, and we are still doing this today. But we’re all getting older and have decided to deed the property to the Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation when the last of us dies. It was kind of like a flyer that took off and we said let’s try it and see what happens. I think we were all astonished that we were able to pull it off. I still am. Every time I go out there, I’m amazed that it happened.

BM: In a way, everyone at the College comes here new. I think we were all looking to see where we fit. That was interesting and astonishing. The women’s movement was very strong at that time. I went to a consciousness raising group. At home in North Carolina, I was kind of used to being the instigator when women got together, but not here. These women were something else. These women were strong, powerful, educated, well-spoken, and eager to speak. I found myself needing to raise my hand sometimes to be able to say anything. I appreciated them, and I learned from them. For me, it was my association with women in groups like that. The offshoot of that was wonderful coffee, and we’d become friends. For Sandy, it’s his associations with his colleagues. He was so amazed when we came here, and he did a [theater] production for the College. At the school we were a part of in North Carolina, a few professors would come to the shows. At Grinnell, many faculty came. Not only did they do this, but they read, they studied, and some of them even were in the play. When he saw this, he was delighted.

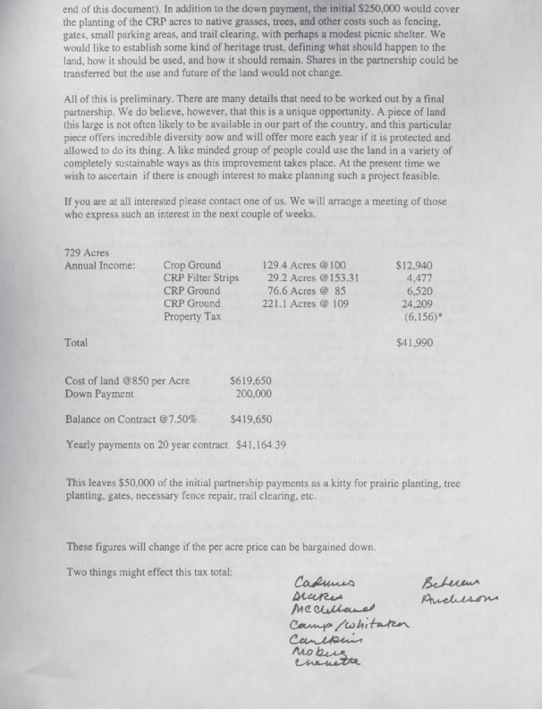

A partial copy of a Letter from Sandy Moffett and partners, soliciting participation in the Pleasant Grove Land Corporation in 1998. Document courtesy of Sandy Moffett

Rootstalk: In his book Becoming Native to this Place, Wes Jackson discusses the idea that you can become native to a place where you were not born. Do you feel that you have become native to Iowa or the prairie in any way?

CH: I feel like it’s partly true. When I walk on campus now, I don’t know many of the people. That’s a point of discomfort for me, my place. In town, I feel that way somewhat. There are places in town I’ve never been to. I’ve never been to Rabbitt’s [Tavern], I’ve never gone to some of the bars, and I know for some of the students that becomes their life and their culture. But I’m not a part of it, and I never will be. I feel native to parts of Grinnell, but I think that’s true for anyone who feels native to an area. You don’t feel native to everything about it or to all the people. But I certainly do—and have for a long time —feel more comfortable here than I do in New Jersey. We’ve been here 44 years. I think it’s partly from having kids, because that draws you into the community really intensely. Very quickly we thought of this as our place. In some ways it feels like you’re native, but you’re also making yourself native. And I’m sure there are some churches that if we gone to them, we would’ve quickly run awayscreaming. In part this would’ve been because of the theology, but also because of the people’s values. We carefully picked our parts of the community to join.

SB: I’ve lived in Grinnell more than anyplace else. I’ve lived here for 43 years. Grinnell is my home. I’m comfortable here with that. I certainly don’t feel native to Grinnell. I’m accepted by those who are native to Grinnell. I think they find it a little exotic that I’m from a foreign country. I don’t feel like I’m a native of anywhere in particular other than Austria. People have asked me if I could go back and live there now. And no, I couldn’t. Austria is home, there’s a deep connection, but culturally I’m too far away from that. I’m without a nation or native place. It’s a unique situation that has to do with Grinnell and Iowa. I can amend that. I can feel native to Grinnell, but not native to Iowa. I think that has to do with the unique situation of Grinnell as an enclave. It’s like a little island within Iowa. Grinnell is quite different. Culturally, I don’t think I could consider myself a native Iowan, but I could consider myself a native Grinnellian. But again, that’s the cultural aspect of Grinnell and the College. The cosmopolitan nature of the student body appeals to me and speaks to me.

SM: Absolutely. I do feel native to this place. We’ve lived here since 1971. That’s most of our lives. When I was doing the political thing, people made a big deal about being born in Iowa. I would counter that by saying ‘no, I wasn’t born in Iowa. I chose to live in Iowa.’ If you’re born in Iowa, you don’t have any choice. To me there is something to that. People make a big deal about being born somewhere, but I was born in China. I certainly don’t feel like I’m native to China. Our social life here was based around the College, but until fairly recently I didn’t feel a huge connection to the city of Grinnell. I felt a connection to [Poweshiek] County [where Grinnell is located]. The connection gets weaker and weaker as you get further away. I don’t feel that connected to Sioux City, Iowa, or Davenport. At that point, I feel connected to the Midwest. And that border, Iowa, do I lose my connection once I get to the Mississippi River? I think I feel more Midwestern than I do an Iowan, but Iowan gives it a name.

BM: Yes. I think there are compartments in my heart. North Carolina has a little compartment in my heart. That’s where I came from. Where am I from now? I’m from Iowa, and I’m proud of that. I feel native to Iowa as a whole, maybe unfairly because there are parts of Iowa I’ve never been to. We have a relative who lives in Atlanta, and he says Atlanta would be a great place if it wasn’t surrounded by Georgia. But I don’t feel that at all about Grinnell. I think Grinnell benefits from being surrounded by Iowa. I think Iowa helps Grinnell not to take itself too terribly seriously. If you’re lucky, you’re connected to what you’re familiar with. This is what we’re familiar with, and we’re lucky because we like it.

Listening closely to what these four individuals said, I noticed everyone talked about how their assimilation—into the town, or Iowa, or the prairie—took time. The ways they assimilated were fascinating to observe. For all of them, it started with the community stemming from the College. Having children seemed helpful to some, as it forced them to be involved to enhance their children’s lives. It was interesting to see how they all joined organizations within the community. For many, it was through a position of leadership, whether it be through being a board member or holding a political position. The integration through social groups outside of the college also caught my eye. Everyone seemed to have found their own way of being involved in social groups. Whether through church, a dinner club, consciousness raising groups, or land restoration, they all were able to establish a social network. Relating to Sandy’s land restoration, I was intrigued to see how each of the interviewees was drawn into their surroundings by nature in some way. When considering how I would become native to some place, for me it would basically all be done through connecting socially. Seeing other ways that people have found their sense of home and how it is different from mine was something that I found compelling. How far each of their unique ways of feeling native evolved was also interesting. For Chris Hunter and Sigmund Barber, they only feel native to Grinnell as a town. For Sandy and Betty Moffett, they feel native to Iowa and, by extension, the prairie.

An American woodcock (Scolopax minor) hen and her chicks at the Pleasant Grove Land Corporation. Photo courtesy of Sandy Moffett

I think about my own assimilation to the prairie. Up to this point, I’d say I haven’t had the easiest time connecting to the prairie because it is nothing like what I’m used to. Yet, seeing my friends love it here makes me feel great for them, and seeing them happy where they are helps me feel more confident about living on the prairie. Although I may not be as comfortable in Grinnell as my friends are, knowing that people who have lived here for a long time went through a similar acclimatization makes me hopeful that I could find what everyone else has in Grinnell. For me, I tend to think that my assimilation could be closer to that of Chris Hunter or Sigmund Barber. The prairie region that surrounds Grinnell is one that I am not familiar with, and I’m not sure if my four years at Grinnell will be enough for me to truly appreciate what surrounds the College. If anything, I think I could maybe become native to Grinnell. If this is the case, maybe I’ll stick around and spend a lot more time within the prairie. And who knows? Maybe I’ll become native.

Prairie sunflower (Helianthus Spp.) Photo courtesy of Sandy Moffett

“Kanis Painting” by Tilly Woodward. Woodward painted the work (11 x 8.5 inches, oil paint on paper mounted to archival mat board) for the Kanis family in 2021 as a trade for “a really nice saddle.” The items in the painting include things from their farm—duck features and a duck’s egg, a roweled spur, and a chess piece that resembles the marking on one of their first horses’ nose.