I’ve never considered myself an avid astronomy fan, but I have always enjoyed looking at the night sky. Its distance makes it mysterious; a twinkle in the sky could be a star, a planet, a distant galaxy, or something else entirely. The mere knowledge that many of those pinpricks of light up there are the same ones that my ancestors also likely saw, marveled at, and told stories about, even if they were in a completely different part of the world, is magical.

I grew up in Dallas, Georgia, a suburb about 32 miles northwest of Atlanta. Its historic downtown boasts old boutiques and town museums rather than towering skyscrapers or sprawling centers like the state’s capital, but it’s still not the best place to do any sort of stargazing. This wasn’t something I realized until I moved to the Midwest, specifically to the town of Grinnell, Iowa. One of my earliest realizations of the difference between the rural Midwest and the suburban Southeast happened the night that I was with a group of fellow science pre-orientation students in the middle of one of Grinnell College’s athletic fields hoping to see the Perseid meteor shower.

As we were walking to the field, I remember being struck by how far from any artificial lights we seemed (at least in comparison to where I was from), and how the darkness of the night on the prairie was darker than anything I’d ever experienced back in Dallas. We laid out blankets, and one of our upperclassmen guides told us to lie down and look up.

The stars sparkled like someone had spilled thousands of tiny diamonds across a deep black carpet. Backset against them all was a mottled blue-purple haze that I would later learn was the body of our Milky Way galaxy. Then, there were the Perseids themselves. They were quick flashes of playful blink-and-you’ll-miss-it streaks that had me staring for so long I had to remind myself to blink. We stayed out there until the stream of meteors slowed to a trickle. Even after the shower ended, I was still captivated by the sky. By that point, however, others were grumbling about being tired or cold and I didn’t want to stay out there by myself, so we packed everything up and headed back to our dorms.

Over the following months, I tried to gain a more nuanced understanding of the night sky. I went to an Open House at Grinnell’s Grant O. Gale Observatory and attended a couple of Astronomy Club meetings, but I wasn’t quite able to replicate the feeling of breathless awe that I had experienced during that original night of stargazing. As time went on, my sense of fascination faded into more of a passing interest. The night sky became merely a reason for me to crane my head upwards as I walked back to my room in the evenings.

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2022-spring/thompson-2.png)

Watching a meteor shower from a field near Grinnell College’s Grant Gale Observatory. Photo by Scott Lew

For the purposes of this article I decided to revisit that interest. My initial inquiries led me to interviews with three people in the area who collectively have decades of astronomy experience: Professor Bob Cadmus, a longtime member of the College’s Physics department; Dr. James R. Paulson, a local physician and amateur astronomer who built his own observatory about five miles east of Grinnell; and John Johnson, Outreach and Promotions Director of an astronomy group called the Nebraska Star Party.

Some, looking up at the night sky, feel miniscule. In the grand scheme of the cosmos, Earth is but a tiny celestial body floating amongst countless other celestial bodies. While the odds of life existing on other planets is high in our infinite universe, until we find evidence of complex beings such as ourselves elsewhere in the galaxy, we are alone on this ball of rock. To some, this is a daunting notion that engenders existential dread and creates questions about the meaning of our finite lives. Grinnell’s Bob Cadmus has a completely different perception.

“[People] say, ‘Oh, whenever I look at the night sky, I feel so insignificant.’ And they seem depressed by this. That’s the exact opposite of the way I feel. When I look at the night sky, I feel privileged and fulfilled… I can spend hours lying on my back and looking [up].”

Cadmus appreciates the night sky as an opportunity to relate to people, believing the view is a “resource for everybody.” If understanding the stars and their celestial companions is enjoyable to him, the ability to introduce visitors and newcomers to the Midwestern night sky is equally rewarding.

Dr. Paulson feels the same way. Despite joking that “amateur [astronomers] are nuts,” he fondly recalls summers stargazing with kids from the town, showing his night sky photography at the Grinnell Area Art Center and at the Science Center of Iowa, and even driving all the way from Grinnell to Car Henge in Nebraska to experience the 2017 solar eclipse with hundreds of others.

The passion Cadmus and Paulson feel for space and the stars makes them fierce advocates in the effort to preserve the night sky. Such advocacy is necessary, they told me, because the view that captivated me in my first year on the College’s athletic fields is actually under threat.

This threat stems from phenomena both natural and human-produced which are obstacles to clear night skies. In addition to light pollution from populated areas, there are less-obvious phenomena which make astronomy difficult. These include heavy greenery, humidity, and large bodies of water. Paulson grew up near Lake Michigan, which often created clouds and haze, while Cadmus grew up near forests where his view of the sky was often blocked by trees. Humidity can cause light dispersion effects that create distracting halos of light around the very celestial bodies you’re trying to look at.

Image of Comet Hale-Bopp taken by Bob Cadmus from the Gale Observatory in 1997. The lights of the City of Grinnell are blurred because the camera was tracking the comet. It is clear that the town’s lights affect the view from the observatory

Given that fairly little can be done about natural barriers to clear skies, the efforts of astronomers like Cadmus and Paulson have centered on a problem caused by human activity: light pollution. Researchers in a joint study published last year by the Complutense University of Madrid the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia and Exeter University estimate that the increase in light pollution from 1992 to 2017 was 270 percent globally, and potentially up to 400 percent in certain regions. The study’s authors pinned the blame for the increase partly on solid-state light-emitting diodes, also known as LED lighting.

LED lighting has been championed as an energy-efficient, low-emission and low-cost method of illumination. That it’s inexpensive compared to other lighting methods has made it a light pollution problem because, as more and more people and businesses use it to illuminate outdoor spaces, it further degrades the experience of viewing the night sky. Additionally, this profligate use of artificial lights causes problems for nocturnal wildlife. According to Paulson, artificial light interferes with migrating birds, deprives bats of their insect food sources, disorients newly hatched turtles who use moonlight to navigate to the ocean, and interferes with the twilight used to guide arctic krill’s daily rhythms. Paulson said this light can also cause spring to come early by prompting trees to bud before they should, as well as disrupting humans’ sleep rhythms.

These ill-effects have led many to question what can be done about them. In Grinnell, Cadmus and Paulson have pushed for and helped pass a lighting ordinance, modeled on similar laws put in place elsewhere which aims to preserve the view of the night sky and to minimize artificial lighting’s harm to the environment.

Cadmus says he believes the ordnance passed in Grinnell because he and Paulson pitched it as protection for “a valuable natural resource that we should preserve for future generations.”

Light pollution can be mitigated by replacing lights whose translucent globes lack shielding (top image) with partly shielded fixtures (bottom image) in which the fixture reflects light downward. Photographs on Grinnell College’s campus by the author

Characterizing the night sky in this way is one strategy advocates for minimal artifical illumination use to convince local or federal powers to pass night-sky-friendly measures. For instance, Paulson was successful in lobbying Monsanto Corporation when it announced plans to build one of the largest agribusiness plants in the world about a mile from his observatory. Paulson contacted the plant’s engineers.

“I said, ‘Look, guys. There’s this thing called ‘dark skies’ and it’s gonna be a win-win for you. When you design the lights you’re going to have around, if you make them dark-sky-friendly, [it’ll be] great for you guys! You don’t have to spend as much money for energy.’ To my pleasant surprise, they did it!”

In citing “this thing called ‘dark skies,’” Paulson was referring to the efforts of the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), which was started in 2001 “to encourage communities, parks and protected areas around the world to preserve and protect dark sites through responsible lighting policies and public education.”

In practical terms, advancing this agenda has meant fostering conversations about the need to combat light pollution. The IDA has formulated an 11-step action plan to recruit dark sky advocates and create a loose consortium of places prioritizing reduced light pollution.

Cadmus points out that lighting ordinances don’t actually reduce existing light pollution. Rather, they reduce the rate at which things get worse. Cadmus says that while such ordinances are an important early step, public education is equally important, to help people to understand why massive security lights are unnecessary for backyard illumination, or intervening before problematic lighting gets built at all.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t always work. Cadmus provides an illustration from early in his Grinnell career. At that time, there were translucent globe lights on campus that sent significant amounts of light upwards. He used his position on an important committee to try to advocate for the installation of more responsible fixtures. Acorn-shaped globes were one solution then, but the shielding they were equipped with was rudimentary. When the College began a new round of construction and expansion, Cadmus pushed for adoption of the more advanced technologies that had been developed in the interim.

Unfortunately, the College president at the time liked the acorn lights, so many remained. Today, these fixtures stand in contrast to newer lights that provide softer lighting elsewhere on the college grounds.

“We had a great opportunity to really improve the campus and we blew it,” Cadmus said.

The nine-class Bortle scale measures the quality or brightness of the night sky for a given location. Class 9 represents an “inner-city sky” that is brightly lit, rendering many stars and certain constellations invisible. On the other end of the scale, Class 1 locations are “excellent dark-sky sites” which feature clear naked-eye viewing of celestial objects such as the M33 (Triangulum) galaxy and the path of our own Milky Way galaxy, which it would be difficult to see in a more light-filled environment.

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2022-spring/thompson-6.png)

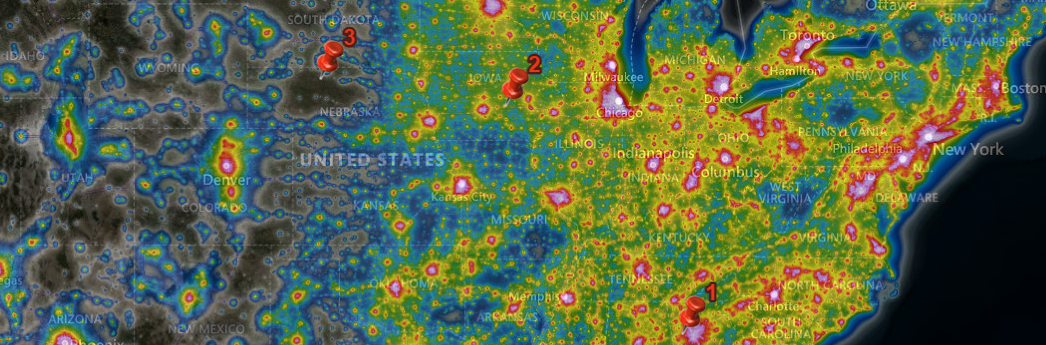

A map depicting the zenith sky brightness, as measured by the World Atlas in 2015. Point 1 is the location of the author’s home in Dallas, GA. Point 2 is the location of the Grinnell College soccer field where she watched the Perseid meteor shower. Point 3 is the location of Merritt Reservoir, where the Nebraska Star Party holds its annual event. Image Credit: lightpollutionmap.info.

According to LightPollutionMap.info, the 2015 Bortle scale designation of the area including my house in Dallas was designated Class 5. This means that the Milky Way was faint there, if not impossible to see. In contrast, the Bortle scale designation of the area including the soccer field where I watched the Perseids was a Class 4. Finding out that the soccer field was only middle of the pack as far as darkness goes was quite a shock. If what I saw was a class 4, then how much darker could the sky possibly get?

As I learned, this would be a good question to ask at a star party. These events, usually held in the summer, attract amateur astronomers who gather to stargaze together. The Nebraska Star Party (NSP) is one of the most famous of these events. The NSP is the annual project of a loose coalition of individuals and groups which sponsor the gathering at Nebraska’s Merritt Reservoir, which, notably, is designated as a Class 1 on the Bortle scale). The 2022 event, set for July 24-29, will be the 29th NSP.

It is sites and events like this that really show how stargazing is unique in the prairie region, an area of North America in which there are large zones of low-density settlement. Less densely populated clusters mean less light pollution, which allows for experiences like the ethereal sensation of seeing shadows cast by the Milky Way on your hand.

For John Johnson, the NSP’s Outreach and Promotions Director, a large part of the joy he finds in astronomy comes not merely through the study of the planets and the stars themselves (though the hundreds of astronomy books he owns may suggest otherwise); it comes via sharing the experience of stargazing with other people. To him, it’s a bittersweet feeling of “connecting with nature and being out there with this beautiful sky, and then the sadness of knowing that probably 75 percent of the world’s population does not, can not, and will not have that experience.” This realization forms the cornerstone of his conviction that people need to understand just how harmful the brightening night skies are.

“I get to the point where I just want to grab and shake people and say, ‘Do you realize what we’re doing?’” he said. “I’ve done all the studying. I’ve got videos, I’ve got proof, whatever proof you want, about how it’s affecting society, humans both psychologically and physically, and it’s obviously detrimental for nocturnal animals.”

He has been working hard for decades to bring to more general awareness both the wonders of the night sky and the threats to experiencing them. He is a passionate advocate for the International Dark Sky Association agenda.

A Unihedron Sky Quality Meter (SQM) and its accompanying information card, given to the author by Dr. J. R. Paulson. SQMs are used to measure sky brightness, an important step in the process of applying to be a dark sky location. Photo by the author.

Along with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission and the rest of the Nebraska Tourism Commission, Johnson has worked to designate Merritt Reservoir and the surrounding area as a dark sky sanctuary. According to the IDA’s website, this label identifies the most dark and remote places in the world “whose conservation state is most fragile” but otherwise has few nearby threats to the quality of its darkness. Upon certification, the IDA works with a given site to promote their work and enhance their visibility to the world at large.

Like Cadmus and Paulson, Johnson has laid the case for the value of this particular dark sky sanctuary before the relevant federal powers by emphasizing the economic benefit of the designation.

“If a bunch of wild-eyed astronomers start beating on their chests saying ‘Oh, we gotta shut all the lights off!! We got to be able to see the stars!’ That doesn’t fly,” Johnson said. “What flies is when you [say], ‘Well, you know how many more destination tours we could get out here? How much more money [tourists] would spend around the state if we had areas designated as dark sky sanctuaries where they could come out and really see the stars?’”

pummeled the Midwest. the storm an estimated $7.5 billion in damage and knocked out power to a wide area. Grinnell was in the blackout zone. Peter Hanson, a Grinnell College faculty member and amateur astro-photographer, took pictures immediately after the storm while the power was still out and again in the same spot days later when power had been partly restored. The effect of light pollution on the same stretch of sky is stark. Photo courtesy of [Peter Hanson](https://sites.google.com/view/peterchanson/night-sky-imaging?authuser=0)](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2022-spring/Thompson-8-volume-viii-issue-1-spring-2022.jpg)

On August 10, 2020, a derecho with winds up to 120 mph pummeled the Midwest. the storm an estimated $7.5 billion in damage and knocked out power to a wide area. Grinnell was in the blackout zone. Peter Hanson, a Grinnell College faculty member and amateur astro-photographer, took pictures immediately after the storm while the power was still out and again in the same spot days later when power had been partly restored. The effect of light pollution on the same stretch of sky is stark. Photo courtesy of Peter Hanson

As of this writing, Johnson and his fellow amateur astronomers are still trying to get Merritt Reservoir recognized as a dark sky sanctuary in order to preserve the pristine dark skies above in the area.

During Fall Break in 2021, I went on a camping trip with the Grinnell Outdoor Recreation Program (GORP). The trip happens annually, COVID years notwithstanding, and one of our destinations was Pikes Peak State Park which is known for its sweeping views of the Mississippi River.

One evening while we were there, one of the trip’s two student leaders invited everyone to go on a night hike. I was immediately game for the adventure. Our leader took us through the woods along trails that we’d explored earlier that day, which suddenly seemed so much more menacing as we kept getting spooked by the reflecting eyes of nearby deer and racoons.

We eventually reached a tiny trickle of a waterfall by the name of Bridal Falls. Directly behind the dripping curtain of water was a little hollow, likely from years and years of the water eroding away the rock. Our student leader was the first to slowly pick his way down the slippery dirt-turning-rock path to go sit in the hollow. The rest of us gingerly followed suit.

Directly in front of us and across the Mississippi River, we could see lights in the state of Wisconsin. The view was spectacular in some ways, with its clear path across the state border to hibitation miles away from us, but I found myself struck by the sight of the sky. Right above the cityscape was a halo of yellow haze being cast up into the air.

In the moment I had felt at peace, basking in the quiet with the other students after a long day of hiking. Looking back, though, I don’t recall seeing a single star. The twinkling of the artificial city lights drowned out the natural sparkle and splendor of the stars above.

Despite the fact that the Midwest is a far better place to stargaze than my hometown, bigger urban centers like Chicago or the Twin Cities show that the Midwest is by no means immune to light pollution. People like Cadmus, Paulson, and Johnson are putting in hard work to protect the Midwestern skies as much as possible, but it’s going to take a lot more than just them to make a dent. The more people that join the movement to protect one of our most overlooked natural resources, the longer we’ll be able to save it for future generations to enjoy.

(CERA). Photo courtesy of Justin Hayworth](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2022-spring/Thompson-10-volume-viii-issue-1-spring-2022.jpg)

Visitors stand beneath the Milky Way at Grinnell College’s Conard Environmental Research Area (CERA). Photo courtesy of Justin Hayworth