“We as a nation, and as individuals, are much defined and explained by the great empty middle of our continent, which is the grassland.”

Thirty-four years ago, my husband, Chuck, and I left our rural home in North Central Iowa. For ten years, from our tiny makeshift house on a hill, we looked south to an eighty-acre field and, beyond that, a wooded Iowa River valley. Toward the east, a hillside pasture lay between our house and the Kelsey home place, where my in-laws lived. I still dream about cornstalks, emerald green in midsummer, picnics near the river on blue-sky fall days and woodlands white with snow.

The little house has been razed, but Chuck and I still own forty acres of pasture and woodland. And we wonder, from our temporary home in California, how best to tend to that land that has a history of its own and needs that commerce can’t address.

After the Ice Age ended in North America about twelve thousand years ago, silt and rock particles left by winds and retreating glaciers became the foundation of soils for a fertile tallgrass prairie covering 142 to 169 million acres of the Midwest, including 80 percent of what we now call Iowa. The only state totally inside the tallgrass prairie region, Iowa’s 28.6 million acres of prairie were among North America’s most diverse and biologically productive lands.

The prairies must have once been a colorful sight to behold spring through fall as broad leaf flowering plants known as forbs mingled with prairie grasses and blossomed into purples and blues, yellows and oranges, even bright reds. The roots of prairie plants go down five, eleven, even up to twenty feet deep, interlocking and hosting tremendous microscopic diversity. The underside of a developed prairie has been likened to an upside-down rain forest, with two-thirds of the biomass resting below the surface.

For centuries, Iowa’s prairies, wetlands and woodlands hosted bison, elk, white-tailed deer, wolves, bear, prairie chickens, waterfowl, fish and many other animals and insects. Drawn by large animal herds, Indigenous peoples migrated into Iowa approximately thirteen thousand years ago. In 1838, under pressure from the US government, the Ioway people signed a treaty ceding their lands between the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers—now Iowa’s east and west borders—and were removed to reservations in the West along with other native tribes. Four years later, the Meskwaki tribe ceded their Iowa land and were moved by the government to a reservation in Kansas. Only the Meskwaki tribe returned and were able to purchase a small amount of land in Tama County, and today are the only independent Native American settlement in Iowa.

The land was quickly colonized by white settlers, who broke up the prairie to farm like their European ancestors. Sod-busting, it was called. Early cast-iron plows pulled by teams of oxen and men struggled against the deep prairie roots, which when broken sounded like pistol shots. Soon horses pulled John Deere plows made with polished steel that allowed soil to slide off more easily than with cast iron. With the death of the prairie came the birth of black gold: the most fertile soils in the world.

Hillside pasture in winter, 2022 Photo courtesy of Mary Kelsey Martz.

In 1869, my husband’s great-grandparents traveled from New York to North Central Iowa, outside Iowa Falls, to purchase 150 acres of land from a Civil War veteran who had acquired the land through the Homestead Act of 1862. By the mid-1900s, the Kelsey farm included nearly 400 acres and was split between Chuck’s uncle and Chuck’s father and grandfather.

When Chuck’s parents, Barb and Dean, married in 1950, small family farms and rural communities were thriving. Iowa had 206,000 farms with an average size of 169 acres.

While not as aware as we are today of the rich natural history of the ground underneath their feet, Dean and his father shared equipment with relatives as they rotated crops like corn, oats, soybeans and sorghum and raised hogs, dairy and stock cows, sheep and chickens. With few or no chemicals and animals ranging free on grassy pastures, today their farm would be considered a relatively unusual example of sustainable farming.

During the 1960s, after Barb and Dean’s family expanded to four children, Dean sold some of the cropland and rented out the rest in favor of running a milking operation out of the barn and a Harley-Davidson shop out of a small outbuilding a few steps away from the farmhouse. Harleys were the true passion for the young father, who won regional awards for motorcycle hill-climbing contests.

Barb and Dean Kelsey, 1985. Photo courtesy of Suzanne Kelsey.

My in-laws led big, satisfying, meaningful lives living near Iowa Falls. Barb’s love of cooking served as her social currency. Notorious for insisting on setting an extra plate, she often fed Harley customers and other visitors who learned to time their arrivals for mealtime. She volunteered with many organizations in town, including 4-H and the United Methodist church.

Country living offered a kid’s paradise combined with hard work. By third grade, my husband, Chuck, rose at four thirty each morning to milk cows before school and did the second milking after school. His sisters helped clean the house, cook, bake and preserve fruits and vegetables. But the entire family wove play into work throughout the day. Between chores, they went for Harley rides with the kids piled into a sidecar. They hosted dinners with extended family and gathered with neighbors at an old country school for potlucks and softball. They took vacations around the US in an old hearse, their vehicle packed full of fried chicken, potato salad and homemade pickles. Back at home the kids explored woodlands and creeks and played cops and robbers on ponies and minibikes. Barb once told me she would send the kids out to play with a silent prayer that they stay safe. Except for minor mishaps leading to stitches at Doc Steenrod’s in town, the kids stayed miraculously healthy.

Marjorie, Chuck, Mary, and Sandy Kelsey, 1959. Photo courtesy of Suzanne Kelsey.

Until one didn’t. In 1959, my husband’s oldest sister, Sandy, became ill with aplastic anemia. Dozens of families and friends pitched in to help care for Chuck and his two other sisters while Dean and Barb ferried Sandy to and from the children’s hospital in Des Moines, ninety miles away. She died in 1960 at the age of nine.

Doctors speculated that farm pesticides might have triggered the young girl’s cancer. The use of agricultural chemicals was quickly expanding. During WWII, the US used DDT on tropical insects that carried malaria and typhus, saving the lives of thousands of soldiers. After the war, use of chemicals exploded in the US and other parts of the world.

By 1950 about 11 percent of the corn grown in the US was treated with herbicides, but the percentage rose steadily as the fifties and sixties went on, significantly increasing yields for farmers during what came to be known as the Golden Age of Pesticides. As early as 1962, Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring, pointed out correlations between the use of pesticides such as DDT and other chemicals and cancer, leukemia and genetic damage in animals and humans. However, by 1982, 95 percent of corn grown was being treated with herbicides..

Whether young Sandy Kelsey died because of ag chemicals used near her home or on her fruit will never be known for sure. In 1971, when I arrived on the scene at the age of fifteen as Chuck’s girlfriend, I noticed that Barb vigorously scrubbed produce with organic liquid cleansers, unlike my own mother, who casually ran fruits and vegetables under water. Barb also urged upon her family an ever-growing pile of vitamin and mineral supplements from a transparent plastic chest the size of a large jewelry box. It sat as the centerpiece on the kitchen table.

In 1978, I finished a bachelor’s degree at the University of Iowa. Chuck, only halfway through his bachelor’s, had a vision for himself that didn’t need a degree: he wanted to go into business with his dad. A few years earlier the Harley-Davidson corporation had tried to pressure Dean into moving his shop to town. Preferring to work from his land, Dean instead established a junkyard full of old autos and car parts. Chuck wanted to help his father transform the yard into a professional-grade salvage business. Old and damaged cars, sprawled over twenty acres, made decent money when parted out. Eventually the cars were smashed on-site and hauled away by an independent company. Prices for recycled steel were strong.

Farmers were doing well, and in rural Iowa, what was good for them was generally good for the auto salvage business. Earl Butz, US Secretary of Agriculture during the Nixon and Ford administrations, had advocated policies leading farmers to engage in “fencerow to fencerow farming,” to “get big or get out,” and to “adapt or die.” The extreme fertility and flat, easy-to-till ground in North Central Iowa enabled almost any land to be used for crops.

Farmers ploughed their fields in the fall to ready them for spring planting. Very few at that time used no-till or cover-cropping practices to help the soil retain and replenish nutrients. After fall harvest and until winter snows came and melted, fields stood bare and black until the first seedlings poked through the ground in May or June. Farmers who finished harvest and ploughed the earliest in the fall were considered most proactive. Those who obeyed Butz’s slogans were experiencing economic heydays, tilling more ground wherever they could.

Until the farm crisis happened. By the early 1980s, rising land values toppled after the Federal Reserve prompted changes in lending policies to stem inflation. Some farmers, encouraged by banks to incur loans for increasing the size of their farms, became overleveraged and unable to pay the interest. Rural banks began to close. A local bank, which had held Chuck’s and his father’s salvage business’s building and operating loan, failed. A bank in Chicago took over the loan, promptly spiking interest rates even higher and lowering the term, forcing Chuck and his dad to reduce their salaries and lay off employees.

Once-busy retail stores in Iowa Falls began to empty or were filled with antique or secondhand shops, the kind still ubiquitous in small towns across the Midwest. For every four midwestern farms that went under during this time, one rural business closed. Kelsey Auto Salvage hovered in the balance.

From 1979 to 1988, even as Chuck’s salary dwindled by half and then a fourth, in every season, we enjoyed the beautiful views from the little house on the hill overlooking the Iowa River valley. Our sons enjoyed spending time with our four parents and Chuck’s grandmother. Our inventive circle of friends held annual art openings complete with handmade art and culinary entries, dancing and dress-up attire gleaned from thrift stores. There were barn parties and summer brunches and long biking trips. It was easy to belong in North Central Iowa.

Our social network didn’t negate my frustration with a lack of employment opportunities for my newly minted secondary teaching certification. Riding around the countryside with my congenial boss to sell Farm Bureau hail insurance to farmers, his tobacco cup placed precariously on his windshield, I observed the vast, open fields of corn and soybeans. I didn’t yet know that less than one-tenth of one percent of the native prairie areas remained of the 28.6 million that once existed in Iowa.

Neither did I know that Iowa was the most environmentally altered state in the US.

After I took a job at a veterinary supply company taking phone orders from feed dealers and veterinarians, and as the farm crisis deepened, the owner would breeze through the telephone sales office, cigar in hand, reminding us he could earn more on his money with a CD note. There were occasional back-alley sales of outdated or banned chemicals that were perfectly fine, I was assured, for keeping flies away from livestock.

Despite the lowered steel prices and interest rates that hit a record 21.5 percent in 1981, Chuck kept trying to grow his dad’s junkyard business into a higher-grade salvage yard, but it was a struggle. Eventually I began commuting to Iowa State University in Ames for a master’s in English. A teaching assistantship paid for my tuition and offered a stipend that, added to Chuck’s meager salary, helped us keep our heads above financial waters until 1988, when we moved to Iowa City, where I found work as an editor and eventually a community college instructor. Chuck finished his bachelor’s and went on to become ordained as a United Methodist minister. “From saving cars to saving souls,” family and friends joked.

The truth was, we were just trying to save ourselves.

Suzanne and Chuck Kelsey offering breakfast in the Kelsey woodland, 1980. Photo courtesy of Suzanne Kelsey.

Not long after we left Iowa Falls, ethanol started saving the day for farmers—or at least some. Made by fermenting the sugar in corn kernel starch and adding denaturants to make the fuel undrinkable, ethanol is mixed with gasoline made from the extraction of fossil fuels—usually 10 percent ethanol, 90 percent gasoline. The ethanol industry, stimulated by a small subsidy during the Carter administration in the 1970s, grew from about 500 million gallons a year in the 1980s to 2–3 billion in the 1990s. In 2022, Iowa produced 4.4 billion gallons of ethanol derived from corn.

In those early days, corn was seen as a first-generation source for ethanol, with the possibility of using perennial grasses for a lower carbon footprint. It was said that prairies, or at least stands of switchgrass, might replace some of the corn and soybean fields that dominated the state. However, second-generation fuel sources did not materialize. Powerful companies such as Monsanto had vested interests in keeping farmers reliant on chemicals, such as the probable carcinogen glyphosate, better known as Roundup, to grow corn. Government subsidies for corn ethanol became entrenched and continue to support ethanol to this day. Of the 13.7 billion bushels of corn raised in the US in 2022, about a third was used for ethanol production.

More than half of Iowa’s corn crop is currently used for ethanol.

Critics have always been skeptical about ethanol’s carbon footprint given the large amount of fossil fuels needed to grow, harvest and process the corn and transport the ethanol. Some believe ethanol production to be worse for the climate than gasoline.

A 2011 National Academics report noted that in addition to releasing CO2, the manufacturing process also releases higher emissions of ozone, particulate matter and sulfur oxide than other fuels. Nitrogen-based fertilizers used on corn release nitrogen oxide into the atmosphere, which destroys ozone and contributes to a higher greenhouse effect than carbon dioxide. Ethanol also diverts land away from food production. Atlantic writer David Frum has pointed out that the US offering more alternative crops such as wheat, barley, and sunflower oil could help make the global food supply less vulnerable to countries like Russia manipulating food supplies and prices for political purposes.

Because of ethanol and the concurrent explosive growth in the use of CAFOs (concentrated animal feeding operations), the agricultural landscape has shifted significantly in Iowa since we left our home region in 1988. As profit margins have thinned, farmers have needed more ground, larger equipment and more livestock to make a living. Farms in Iowa are shrinking in numbers but growing in size. In contrast to the 206,000 farms in 1950 with an average size of 169 acres, by 2019 there were 85,300 farms with an average size of 359 acres.

While some farmers now engage in soil conservation projects such as planting cover crops to keep the soil anchored and contribute nutrients in winter, others continue to leave fields bare in the dormant season. My home region has been informally dubbed “the Black Desert” by environmentalists concerned about all the rich black soil left out in the open to be eroded by wind and rain. At the start of the 20th Century, the average depth of topsoils was 14-18 inches; by the end of the century, the average depth was 6-8 inches.

Jim and Mary Kelsey Martz’s prairie at sunset, 2022. Photo Courtesy of Mary Kelsey Martz.

The livestock industry also contributes to environmental degradation. Since the early 1990s, several large hog-producing businesses have increased the state’s swine population by more than 50 percent. At the same time, the number of farms raising hogs has fallen by 80 percent. One company headquartered in my hometown, Iowa Select Farms, took five million pigs to market in 2021. These animals never see daylight. Some are so confined in crates with other pigs that they cannot turn around. Continual low levels of antibiotics used on perpetually stressed animals lead to antibiotic resistance that can transfer to humans. Hog manure produced in CAFOs drops through slatted floors and is channeled to large septic tanks. The manure, containing antibiotics and other potentially harmful chemicals, is spread twice a year on nearby fields as fertilizer, but it can filter through underground drainage systems or erode into waterways by rain and snowmelt runoff.

Iowa’s waterways are among the most polluted in the nation, with fecal bacteria from hog manure spread on fields, along with nitrate, phosphorus and other chemicals from fertilizer and pesticides, causing toxic algae blooms in ponds and lakes that receive runoff from those fields. Experts estimate it would take $5 billion to address Iowa’s water pollution problem. Despite many Iowans’ objections to the thirteen thousand hog confinements across the state, Iowa’s swine industry continues to expand steadily, aided by laws that favor hog producers such as Iowa Select.

As the number of farm families has become smaller, small towns that once flourished have declined. Between 2010 and 2020, most of Iowa’s 4.7 percent population growth was centered around the state’s urban areas, including Des Moines, Cedar Rapids, the Quad Cities, Council Bluffs/Omaha, and Sioux City. For rural counties not close to those cities, the population decreased. One need only drive north along I-35 from Des Moines to the Minnesota border to see the Black Desert’s large fields, unbroken by trees and other windbreaks. When you do see a grove of trees, they are often camouflaging a CAFO. Those trees do help filter some of the odors and air pollutants generated by the confinements, but not all. Just ask your nose.

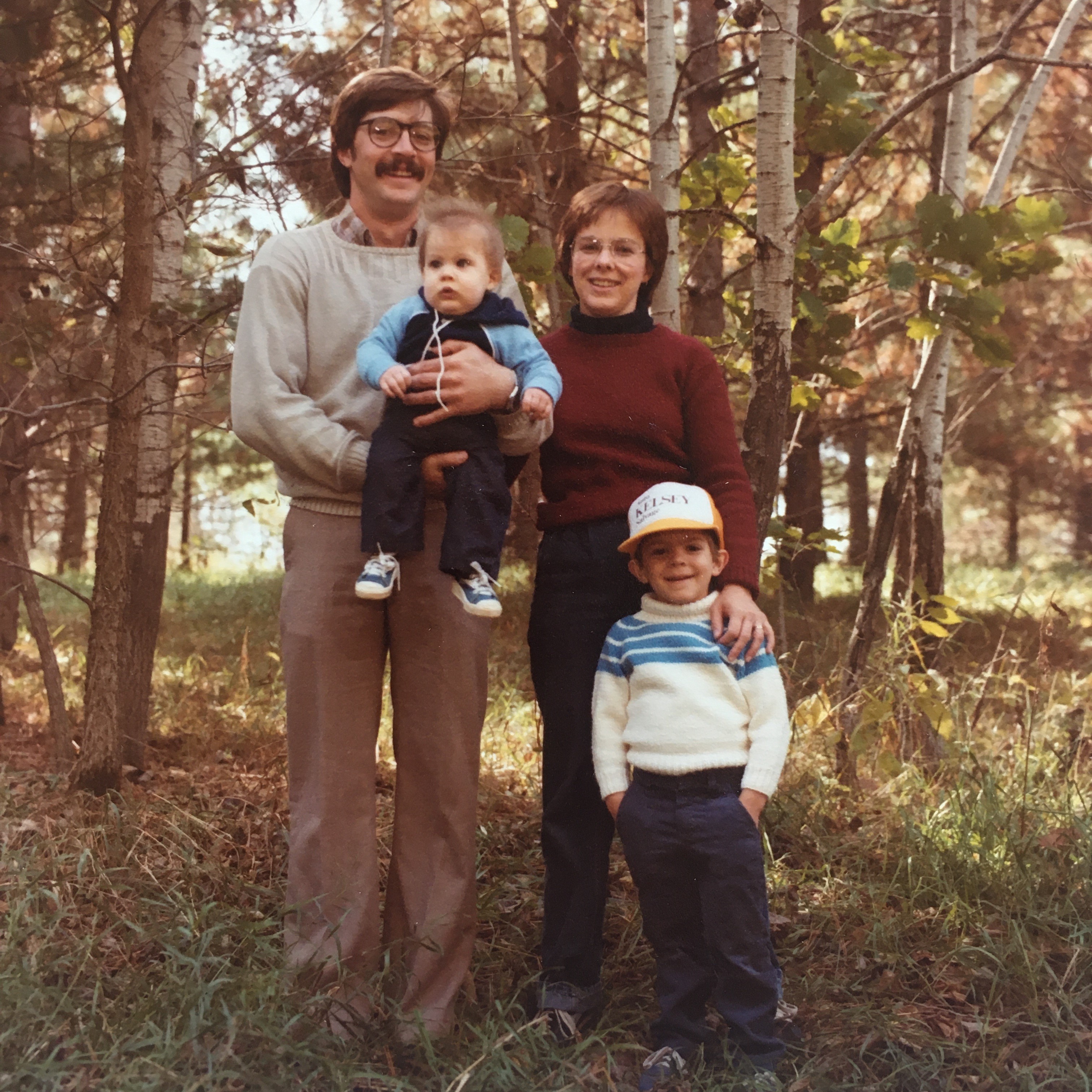

Chuck, Keegan, Suzanne, and Jesse Kelsey in Kelsey woodland, 1983. Photo courtesy of Suzanne Kelsey.

On a cold day in February 2012, an oncology physician informed my seventy-nine-year-old mother-in-law that she had end-stage pancreatic cancer. “It’s too late for surgery,” the doctor said gently. “We can offer palliative chemotherapy. It won’t extend your time, but it may help with nausea.”

Barb wrinkled her nose. “I don’t think so. I know how chemo makes people sick.” Over the years, she’d not only nursed her daughter but also several elderly relatives through their deaths in the living room of her farmhouse. She knew plenty about the ends of lives.

We thought it was caregiver’s stress, a delayed reaction to my father-in-law’s admission to a nursing home several months earlier. He was suffering from memory loss and could no longer walk. As Barb’s cancer progressed, I read about a correlation between people who take mega supplements and those who develop pancreatic cancer. I wondered if her cancer was part of the cost of living in the Black Desert—whether directly from farm chemicals, or indirectly, trying to avoid cancer from farm chemicals by taking all those vitamins and supplements from that plastic chest. For whatever the reason, Iowa has the second highest incidence of cancer in the US.

By early May in 2012, Chuck, his sisters, our brothers-in-law and I were holding a vigil in Barb’s kitchen and living room as she lay in her bed, her face peaceful. As I came to her side that day, I said a silent prayer of thanks for the way she had so graciously accepted our decision to leave the area years earlier. We had left her with no adult children close by, even as the world significantly widened for my family. Our sons had flourished in the Iowa City school system. Both would eventually settle in the San Francisco/East Bay area. Despite taking on the salvage yard operating loan to eliminate remaining debt for Barb and Dean, Chuck and I had dug ourselves out of our financial downslide, built fulfilling careers, and made good friends in Iowa City and other places we’d moved to for Chuck’s work.

The sky darkened, and eventually, like a turnkey clock winding down, Barb’s breathing slowed and stopped. As Chuck’s sisters lovingly wiped her face, I thought about the lessons my mother-in-law had modeled in all the decades I’d known her: Work the land for crops and livestock to sell and for food for your family. Preserve food by canning and freezing. Put a good meal on the table and you’ll always have friends and a way to be of service to your community. When something’s out of your control, such as a daughter dying, adult children moving away, or a stage-four cancer diagnosis, don’t waste time resisting. Live and laugh fully until the very end. And when it’s time, let go.

Ten years past Barb’s death and eight after Dean’s passing, I find myself wondering what my in-laws would have thought about a recently withdrawn $2 billion proposal by a company called Navigator CO2 Ventures to bury nine hundred miles of pipeline through Iowa. The lines would have carried liquified, pressurized CO2 captured from smokestacks of twenty ethanol plants in Iowa. Another 1,300 miles of pipelines would have captured CO2 from other ethanol plants in the Midwest, sweeping from South Dakota diagonally across Iowa and into Illinois, with the CO2 to be sequestrated in Southern Illinois, in an area considered geologically suitable. Some might have been siphoned off for delivery to fossil fuel companies for enhanced oil recovery — EOR — which uses pressurized CO2 for areas where oil is otherwise hard to reach.

Another company, Summit Carbon Solutions, is still proposing a $4.5 billion, two-thousand-mile pipeline that will gather CO2 from thirty-some biofuels plants in Iowa and other Midwestern states and send it for EOR or sequestration in North Dakota.

The Navigator pipeline would have run through the grassy pasture that Chuck and I own and, to the south, through land owned by Chuck’s sister Mary and her husband, Jim, who converted their eighty-acre field to prairie with the help of the federal Conservation Reserve Program (CRP).

The companies proposing the pipelines began their campaign several years ago, asserting to landowners in informational meetings held all over Iowa that it would be years before the US could shed its dependence on fossil fuels. That, in the meantime, the carbon footprint of ethanol can be reduced by capturing the CO2 rather than releasing it via smokestacks, as has been occurring. That ethanol production supports over forty thousand people in ag-related Iowa businesses and continues to ensure a good market for corn growers. That the two projects would potentially capture up to 27 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually, the equivalent of removing 5.8 million gas-powered vehicles from the road. (Approximately 284 million vehicles were registered in the US in the third quarter of 2021. Just over 3.7 million vehicles were registered in Iowa in 2021.)

Despite these claims, many affected Iowa landowners filed objections to the pipelines with the Iowa Utilities Board (IUB), which would decide whether to approve the permits. The three members of the IUB, all appointed by Iowa governors in favor of the project, can grant eminent domain powers if they deem the projects will serve a public purpose. Resistance to both proposals involved an unlikely alliance of Democrats, Republicans, libertarians and environmentalists who argue that pipeline placements, such as the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) that carries light sweet crude oil across Iowa, decrease crop yields, that the projects will lower property values, that carbon capture technology isn’t yet proven to be effective, and that enormous amounts of fossil fuels needed to build and bury the pipelines are not being factored accurately into net carbon capture sequestration (CCS) projections. They point to a CO2 pipeline leak in Mississippi that sent dozens to the hospital.

Resisters complain that taxpayers rather than private investors will foot the bill for the projects. Section 45Q of the US tax code was established in 2008 to incentivize CCS. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 increased the incentive from fifty to eighty-five dollars for each metric ton of carbon sequestered. Without this funding, no CO2 pipeline proposals would be on the table.

Some climate scientists assert that a CO2 drawdown needs to be part of the climate mitigation equation. Jesse Jenkins, a Princeton University energy and climate expert who helped inform the climate mitigation policies made possible with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, has suggested that we need all tools in the toolbox. He acknowledges that CCS is in its infancy but reminds us of early solar energy technology that was aided by significant funds rightfully devoted to research and development.

However, because of the resistance on the part of many Iowans, and the fact that South Dakota eventually denied a permit to Navigator for the project, Navigator pulled its proposal off the table in the fall of 2023. At least for now, our land and that of my brother- and sister-in-law and many others will not be affected.

The Summit proposal is still being considered, with continuing resistance.

Chuck and I are relieved that the Navigator proposal is dead. But I’m still stuck on the irony of artificial steel roots being planted underground to maybe capture the CO2 that prairie roots growing broadly and deeply would take out naturally—that is, if Iowa had any grasslands left besides its few native remnants and restored postage stamp prairies.

A 2018 UC Davis study suggests that prairies may be more reliable natural carbon sinks than trees in certain areas of the country. Forests store most of their carbon in the woody biomass and leaves and release most of their carbon into the atmosphere if they burn; with grasslands, most of the carbon is fixed underground, so it stays in the roots and soil. In stable climates, trees store more carbon, but in a warming climate accompanied by drought and potentially more wildfires, the study suggests that grasslands are likely to retain more.

In the last few decades, many Iowa farmers have begun to adopt conservation practices such as crop rotation, contour farming, minimum or no tillage, and fall cover crop plantings to prevent soil erosion and restore nutrients. Some have begun to limit chemical inputs after recognizing diminishing returns with higher prices. Some farmers are planting more prairie strips, areas of prairie gasses and forbs planted on farmland as contour buffers or edge-of-field filters. In addition to reducing the need for chemicals and improving profitability, prairie strips also offer climate benefits, including removal of CO2 from the atmosphere and storage of soil organic carbon. Strips on sloping hills can reduce nitrous oxide emissions, which have nearly three hundred times the warming impact of CO2, by 75 percent.

The USDA covers about 75 percent of the cost of prairie strips via the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) and also recently announced a goal of enrolling an additional four million acres to the twenty-one million acres already enrolled in CRP. If the goal is reached, an estimated fifteen million metric tons of CO2 would be mitigated each year. The USDA is also funding new initiatives that quantify the climate benefits of land put into CRP. Under its Wetland Reserve Easements program, administered by the National Resources Conservation Service, neighbors who own the lake north of our land will soon be restoring a dozen acres of wetland to improve the quality of the water that runs into the lake. This wetland will also recharge groundwater, protect biological diversity, and provide resilience to climate change by capturing CO2 and other emissions.

Private sector funding for using land for climate control is also beginning to surface, with companies like the Iowa-based Soil and Water Outcomes Fund and Houston-based BCarbon establishing carbon markets for companies to offset their CO2 emissions by paying landowners to keep or establish prairies and grasslands.

More landowners seeking CRP income or even private sector funding to help convert more acres to prairies would benefit the common good of all. By sequestering carbon dioxide and other toxic emissions, prairie perennials can also control soil erosion, protect waterways from pollution from ag and lawn care chemicals, and regenerate soil nutrients that are lost with repeated monocropping. As a bonus, if Iowa would halt the CAFO proliferation and clean up its air quality, the state could become a Mecca for remote workers who want to raise families affordably and with the sense of community and close friendships that Chuck and I have enjoyed in Iowa Falls and Iowa City and other places we’ve moved for his work, including Ames, DeWitt and Mason City.

Kelsey homeplace 2022, owned by Jim Martz and Mary Kelsey Martz. Photo Courtesy of Mary Kelsey Martz.

Professor Jonathan Andelson, cofounder of the Center for Prairie Studies at Grinnell College, also wants to see the expansion of restored and protected prairies, even while the state continues to be used for agriculture. “But we want it to be a healthy working landscape,” he told me, giving the example of a strictly organic, no-chemicals farm in central Iowa with an eight-year crop rotation cycle including corn, wheat, oats, rye, barley, winter and spring wheat, and soybeans. “They raise livestock, have an orchard, the whole thing, all on about 160 acres—an old-fashioned quarter section, which in the nineteenth century was what a lot of farms were—partly because what they raise is organic and can command a premium price. With their own milling facility, they mill and sell cornmeal grits, wheat berries, and barley grits, with lots of business in mail order. It is a healthy agricultural setting.” Similar, that is, to Barb and Dean’s farm — and most other family farms in the 1950s.

Due to an unexpected job offer for Chuck in 2019, we moved out of Iowa for the first time to live near San Francisco and our two sons and their families. We love this area and the proximity to our family, but when we retire in a few years we plan to move back to our home state for its lower cost of living. And because it’s still home.

Maybe we’ll try to make a late-in-life difference in a state we still love but that many Iowans feel has gotten itself into a real environmental mess. Living in Northern California has sensitized me to the increasing threat of wildfires in the grand forests near the Bay Area and the stark reality that world forests are in danger as global temperatures increase. I dream about the way Midwestern prairies could help mitigate climate change as the 2018 UC Davis study suggests. I am grateful for my sister- and brother-in-law putting their land back into prairie, and I am looking into how to manage our Iowa acres of grassland and woodland for even better sequestration of carbon dioxide and other harmful pollutants.

Everyone is altered in various ways by their geography and by the turns and twists that our lives take. Living in one of the most altered states in the US, Iowans know deeply what can happen to a land—and its people—exploited for commercial use. But like the old prairie roots that once supported a healthy, diverse biosphere, Iowans go deep. We’re connected to each other by how our communities, rural and urban alike, continue to produce people who find ways to bloom where planted. We’re connected to the world by the corn we grow that makes steaks and vegan muffins tasty, garbage bags compostable, and yes, for now, maybe makes gasoline a tad less carbon-producing—until electric vehicles and mass transportation alternatives become the norm. And we’re connected to anyone who will listen to our cautionary tale.

Like my mother-in-law recognizing when it was time to let go, this may be a time for Iowans to let go—let go of monocropping and CAFO practices that are degrading the land, water, air, and health of its citizens, animals, and insects. Let go; let some of the land rest.

By restoring it back to prairie.

Perhaps someday in our little state, we’ll not only have even more acres in wind and solar power, but also more acres in prairie to help take the CO2 and other toxic emissions from the air — yours and mine.