During several years of working on political campaigns in Iowa, I have seen firsthand the impact of retail politics—which I would define as the lengths to which a political campaign will travel to court the support of a voter—as a tool for driving turnout and engagement. In tight races, even the smallest touchpoint with a voter can be the difference between victory and defeat. When the Iowa caucuses held dominance as the “first-in-the-nation” Presidential preference contest—which for the Democratic Party faded after the 2020 election—campaigns’ commitment to retail politics meant that the Iowa voter was more accustomed than most to seeing and meeting with candidates and the campaigns’ representatives.

I was a professional political campaign staffer for multiple cycles: the periods leading up to specific elections. Practicing retail politics honed my ability to engage with and listen to differing ideologies and opinions, across disparate communities. I worked closely with and supported leaders as they made the case for my candidate and campaign. The two-day road trip with civil rights champion Congressman John Lewis, chronicled below, is now eight years in the rearview mirror. I think it offers an illustration for both the impact of retail politics and the physical cost of this intensive kind of campaigning. Through its illustration of the vast planning and strategizing that goes into a political campaign, I will argue that being present and living in the moment can be a wildly effective means of motivating change.

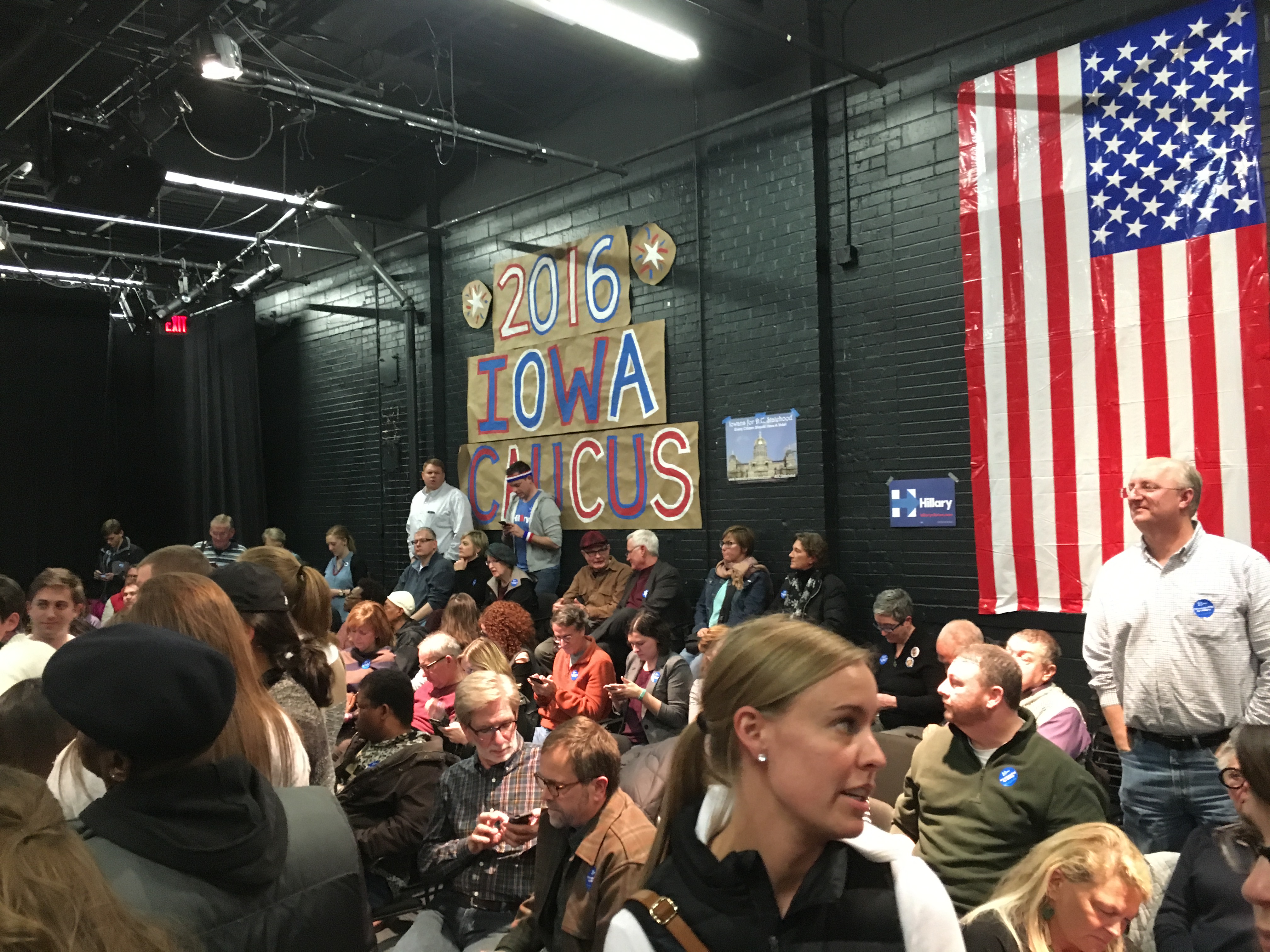

Image from inside the Kum & Go Theatre of the 2016 Democratic Party Iowa Caucus in downtown Des Moines. Photo by Jackson Menner.

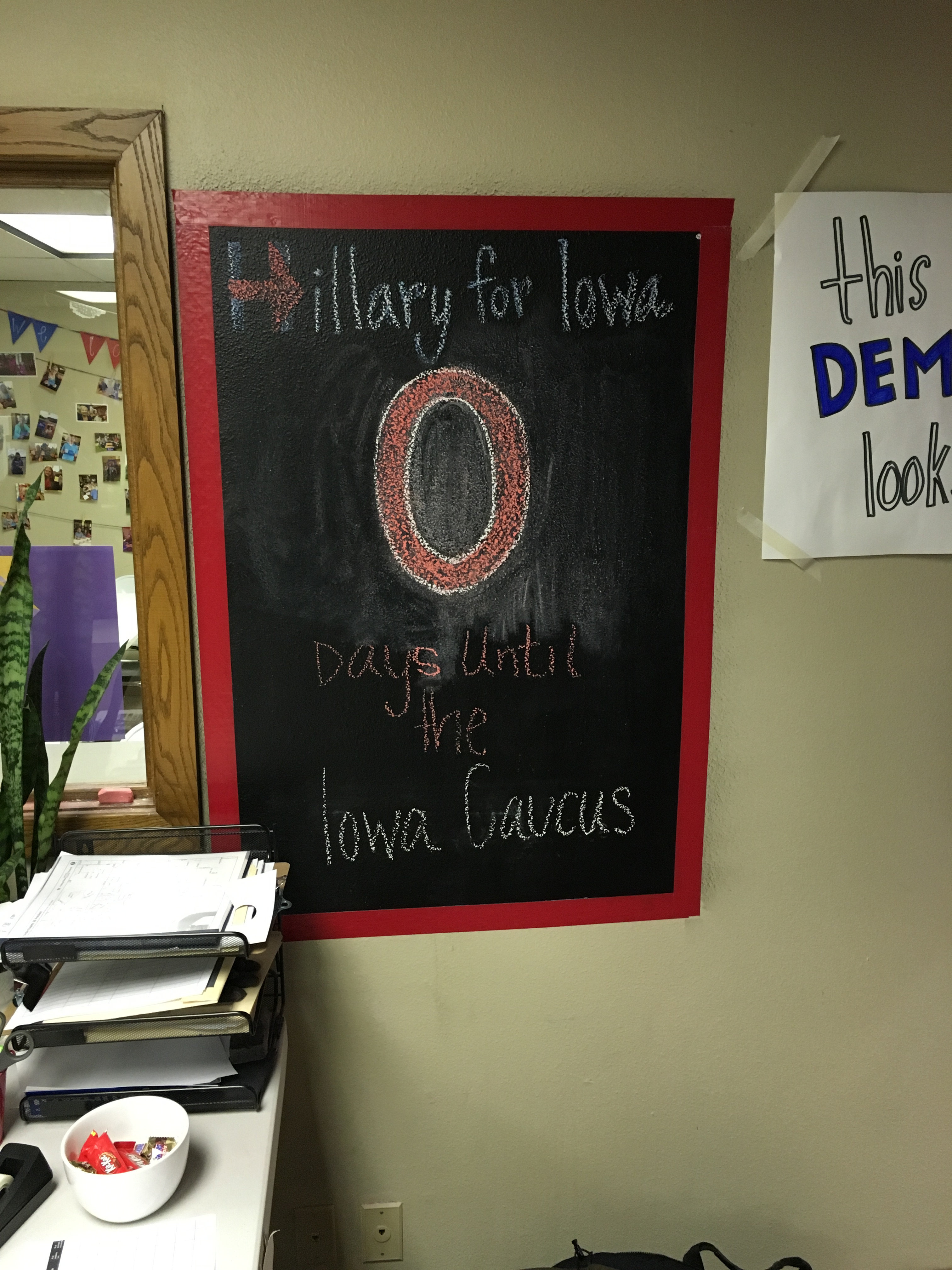

It is early 2016, and I have been with Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign in Iowa for the past ten months. The Iowa caucuses are mere days away, and in a final flurry of activity, principals and surrogates have been crisscrossing the state. Principals are the candidate and her family; surrogates are prominent supporters who lend their faces and voices to the persuasion and mobilization campaign. While my days have largely been spent supporting these trips from my desk at the state headquarters on 5th Avenue in Des Moines, working to solidify details and prepare briefing materials, I have also staffed these trips on the road.

I grew up in Iowa, so the caucuses are familiar to me. Essentially, they are party meetings, distinct from a primary election, which is managed by the state. These meetings take place in venues as varied as gymnasiums, bars, and living rooms. In the Democratic Party model, caucus-goers vote with their bodies, forming preference groups in the room. Delegates who will represent a candidate at subsequent party conventions are awarded proportionally across preference groups, based on the number of people in each corner. In this model, it absolutely matters who shows up. To get the caucus-goers in the room on caucus night, the campaigns build dynamic operations of activists and volunteers to persuade individuals to support their candidate and to turn-out.

How do these campaigns work in practice? If a possible or likely caucus-goer is undecided or sitting on the fence, or if their local organizer can’t convince a supporter to make phone calls for the campaign, knock on doors in freezing temperatures, or be a caucus captain the night-of, then maybe Bruce Springsteen or Bonnie Raitt, could help make the case. I grew up in Grinnell, Iowa, a rural community in central Iowa of about 9,100 people, north of Interstate 80 and halfway between Des Moines and Iowa City. Some of my earliest political memories, maybe selfishly, were Tim Robbins on the stump box for John Edwards at the Eagles Club, the knowledge alone that Scarlett Johansson appeared at a volunteer event for Barack Obama at Pagliai’s Pizza, and the time Herbie Hancock made an appearance playing the piano to turn out support for Al Gore.

Come the final week of January 2016, all the preparatory work is done. The surrogates are either on the ground or due to arrive very soon. We finalize details days in advance, and because our countdown clock has effectively been zeroed out, my pre-caucus desk work has also concluded. I’m told that I will staff a top surrogate, Rep. John Lewis of Georgia, the civil rights leader who marched with Martin Luther King, Jr., who was arrested dozens of times during the Civil Rights Movement, and who was beaten by police while trying to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. He was first elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1986. Lewis is scheduled to campaign in front of largely African American communities, emphasizing the importance of turn-out at the caucuses, and visit campaign volunteers across Eastern Iowa, thanking them for their support.

When I staff a surrogate, it entails driving them and any traveling staff between campaign events and providing staffing support at events, which can include facilitating introductions to local elected officials and party leaders or coordinating with campaign staff and volunteers.

At the airport in Des Moines, I wait to meet surrogates in the arrivals area—I usually sit on the left end of the bench, a few rows back, at the foot of the escalator. With luck, I recognize the surrogate, hop up, and welcome them to Iowa. After stopping at baggage claim, it’s off to short-term parking. From there, it’s either a right or a left turn onto Fleur Drive, depending on where we’re headed, as our time together begins in earnest.

I see Congressman John Lewis as he makes his way down the escalator, dressed in a dark suit and black overcoat, with hand luggage and accompanied by the chief of staff from his House office. There is no mistaking Lewis, with his shaved head and stoic disposition. I note that even while standing still on the moving escalator, he moves with purpose. We have two days of barnstorming—racing across the state to meet with voters and activists—before Iowans head to their precinct-level caucuses on Monday evening.

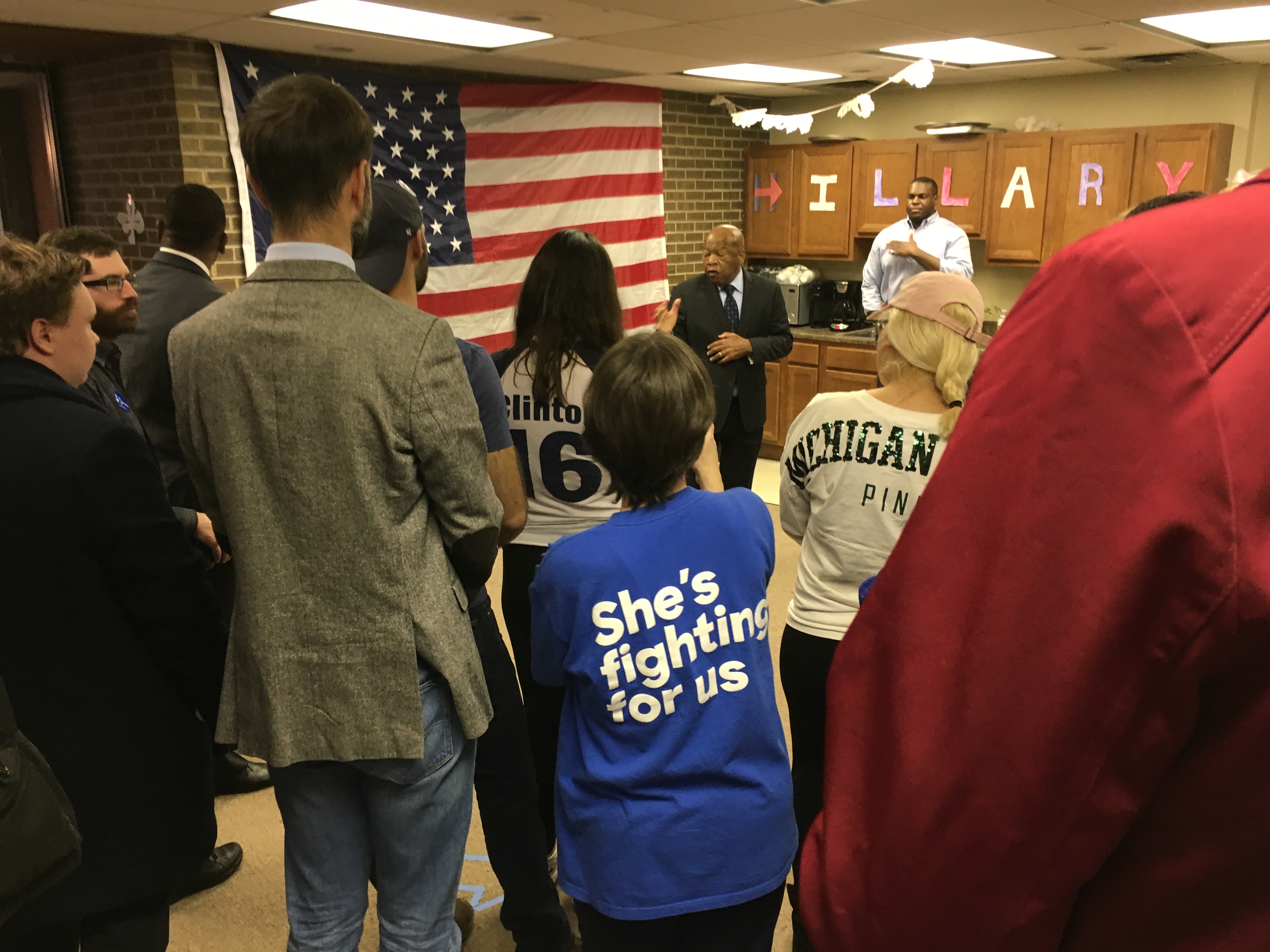

Rep. John Lewis pictured with his assigned Iowa staffer, Jackson Menner, for his visit prior to caucus night in 2016. Photo by Jackson Menner.

We are immediately ahead of schedule, so I ask Lewis if he wants to stop for coffee before we head to Corinthian Baptist Church for Sunday service. He agrees to the pit stop, in campaign speak, an “off the record” visit, and I drive to the Caribou Coffee on Ingersoll Avenue, west of downtown Des Moines. Over coffee, we discuss the campaign in Iowa, and I preview his schedule, which would have him making stops in Waterloo, Davenport, and Cedar Rapids, before returning to Des Moines.

While Caribou Coffee isn’t particularly bustling this Sunday morning, I see fellow patrons initially perk up when they recognize Lewis sitting across the café from them, and then I watch as they muster the courage to approach him and thank him for being a role model, for his life of commitment to racial justice. A few are emotional when they speak. Some ask why he is in Iowa, and he jumps to say it’s to campaign for Hillary before the caucuses. The coffee stop is effective on three levels: I stall long enough to get us back on schedule, I’m able to brief my surrogate on our itinerary, and I am confident that if the folks who we encountered were on the fence about support or whether to participate in the caucus, their encounter with Lewis could shore up their support.

My own impressions of Lewis are that he is unimpeachably human, kind, present, and that he conveys his values in a conversational way that resonates immediately. Over our coffee we discuss his axiom of love, which I would paraphrase as leading with love—even going so far as to love those who don’t love you in return.

Former President Bill Clinton introducing Rep. John Lewis at Corinthian Baptist Church. Photo by Jackson Menner.

Former president Bill Clinton, my candidate’s spouse, is already meeting with the pastor and his family when we arrive at the church to join this pre-service greeting. Standard protocol would have a sitting, rank-and-file Member of Congress introduce a former President. Today, though, is a special day. John Lewis is no rank-and-file Congressman. During the service, after having been welcomed to the pulpit by Pastor Jonathan Whitfield, former President Clinton ends his 32-minute-long remarks, bordering on a sermon, and introduces his friend:

When I met [Lewis, …] he treated me like a normal person. […] If you’ve ever read his autobiography, _Walking with the Wind,_ […] he describes being [in a house] with an aunt and a bunch of his cousins [when] a windstorm came up. And his aunt got all the kids to hold hands with her, and whenever it looked like one corner of the building was going to blow up, they’d walk with the wind to hold that corner and hold it down. Then when the wind shifted, they’d go over there. The point is, not a one of them could have saved that house alone. But together […] they became what he called the beloved community. […] What our founders called the ‘more perfect union.’ What ought to fit well with any religious doctrine: a more perfect union. We will never be perfect, but we can always do better. John Lewis has made everybody who ever knew him want to do better. That’s one thing he has in common with my candidate for President, and I’d like to cede the podium to him.

From the pulpit, Lewis opens by saying, “I’m going to be very brief because the President has said everything. Everything.” He invokes the memory of late contemporaries: “Dr. King and Rosa Parks and others inspired me to find a way to get in the way,” even when the convention was ‘Don’t get in the way.’"

I listen from my seat among the congregation as he vividly recalls violence at Selma: “leading a little church […] after service, to walk across a bridge.” Emphatically, he carries on, “I was beaten, left bloody. Thought I was going to die.” Lewis manages to convey the practice of voting as “precious” and “almost sacred.” The purpose of this visit is to motivate action, and by underscoring the ongoing fight for voting rights and access to polls, Lewis deploys his strongest possible case. From there, the action lies with the congregants to get out the following evening and attend their caucuses.

The church service ends, and the sun is shining. Former President Clinton departs on a separate schedule—he also has a busy schedule in this final push. With Congressman Lewis, we make our way to Patton’s on East Grand for a lunch with local African American leaders, an opportunity to thank activists and supporters before the final day of campaigning. Congresswomen Karen Bass from Los Angeles and Sheila Jackson Lee from Houston join us at the restaurant.

John Lewis speaking briefly at Patton’s Restaurant & Catering on Grand Avenue in Des Moines. Photo by Jackson Menner.

After lunch, as we make our way toward Interstate 235, en route to Waterloo, Congressman Lewis’s chief of staff asks if there’s time in the schedule for a visit to Raygun, the East Village t-shirt shop whose reputation has clearly rippled as far as Georgia. I assure him that we’ll find time to make a stop on our return to Des Moines.

We continue driving north on I-35 when, somewhere in Story or Hamilton County, I scan the tree line and see a bald eagle. It is my first of the day. On a two-hour drive this time of year, I routinely see as many as a dozen eagles, perched in the trees near water or flying above fields. I point out the eagle to the chief of staff, who is seated in the passenger seat. As excited as the chief of staff is to see the eagle, his excitement is eclipsed by the frustration voiced from the back seat: Lewis has been resting his eyes and missed the eagle. Lewis’s frustration aside, I want to show him an eagle before our time together ends.

One of the joys of staffing surrogates in my home state is to show off its grandeur to visitors. Earlier in the cycle, I took Julian Castro, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, to Grant Wood’s American Gothic house in Eldon. I made a detour with former Czech-born Secretary of State Madeleine Albright to drive through Cedar Rapids’ Czech Village. To show Congressman Lewis an eagle—especially after this near miss—would be a personal victory.

A foggy evening in the farmland of rural Iowa, 2016. Photo by Jackson Menner.

Almost on cue, the sun disappears behind the clouds, and the sky remains heavily overcast for the remainder of our drive to Waterloo. However, given the frequency of my bald eagle sightings, I am confident that we will see another. The sun sets at around five-thirty, so we roll into town in the dark. We are headed to the field office on Fourth Street, and again, we are ahead of schedule.

With ten minutes to stall, Lewis asks if we can find a grocery store, and we find a corner market. Lewis buys a couple bunches of bananas, explaining that they will be a gift to the organizers and volunteers. The Congressman thinks—which is likely a correct assumption—that at this stage in the campaign there is little fruit at the campaign office, let alone potassium. It is an insight into the tangible way he views activism: a long game where smart work and thoughtful planning facilitate prolonged effort.

Bananas in hand, we walk into the office which is bustling with activity. Lewis is there to launch a GOTC (“Get Out the Caucus”) canvass, energizing volunteers before they go out to knock on doors. The volunteers will seek to talk with individuals who the campaign’s modeling says would be Hillary Clinton supporters if they attend the caucus. In the final days, the emphasis is placed on the supporters who needed an extra push to convince them to turn out on caucus night. This turnout operation is the culmination of months of an extensive organizing effort across the state. Each time I have visited the Waterloo office, there has been a consistent buzz, but with a surrogate like John Lewis, the room is now electric.

Quinten Hart, elected Mayor of Waterloo the previous fall—and the first Black man to hold that office—takes the microphone and introduces the Congressman. Visibly emotional, he explains that he is “almost in tears today because as a younger person beginning my political career––and I look at all the people out there––this man right here was one of the top people that I wanted to shape my career after.” Mayor Hart fights back tears, his voice wavering, as he finishes his introduction by quoting Roll Call’s reference to Lewis as “‘a great American hero and a moral leader.’”

John Lewis speaking after being introduced by Mayor Quinten Hart of Waterloo. Photo by Jackson Menner.

As this representative of a younger political generation hands the microphone to an elder statesman, keeping their respective visions for their communities in mind, I feel myself stirred toward action. That is the exact point: fire up the volunteers to go out into the cold winter night to knock on doors.

In his remarks, Lewis leads with gratitude, thanking the mayor for welcoming him to the city and thanking the volunteers for their hard work and for continuing to show up. “But we must remember,” Lewis continues, “what Dr. King said many years ago: ‘We must learn to live together as brothers and sisters. If not, we’ll perish as fools.’”

Lewis then channels the activist A. Philip Randolph, with whom he helped to plan the 1963 March on Washington, saying: “‘Maybe our foremothers and our forefathers all came to this great land in different ships, but we’re all in the same boat now.’” To bring it home, Lewis offers his own assessment, that “we’ve got to look after each other, take care of each other, and never, never forget that we all live in the same house. Not just the American house, but the world house.”

At a volunteer launch, unlike a campaign rally, the speaker isn’t the main event. There is an emphasis from the organizing staff on making an ask—to volunteer, give, sign-up. A lingering special guest can stand in the way of this, so Lewis keeps his remarks brief, all the while seeking to energize and excite the staff, activists, and volunteers in the room.

The Waterloo campaign office is our last commitment of the evening, leaving a two-hour drive to Davenport, where we will stay overnight. In the morning, Caucus Day, we start at a GOTC canvass launch, this time at the Davenport field office in a pea soup colored, layer-cake-shaped commercial building on North Brady Street. After Davenport, we head to Cedar Rapids where for yet another canvass launch, as well as a lunch with local leaders at the African American Museum of Iowa.

John Lewis speaking in the Smithsonian affiliate African American Museum of Iowa in the Cedar Rapids area. Photo by Jackson Menner.

Following our commitments in Cedar Rapids, I note that we are 45 minutes ahead of schedule. Congressman Lewis is slated to call into a few radio stations in South Carolina, in advance of its primary in a couple weeks. Our final in-person engagement before I drop the Congressman off at his hotel in Des Moines is a GOTC phone bank at a Des Moines campaign office with Secretary of Agriculture and former Governor of Iowa Tom Vilsack. With almost an hour to play with, I propose that we get off the interstate.

My hope is to carve out a break from what to me feels like a tired stretch of Interstate 80. While working as an organizer in Iowa during the congressional midterm cycle in 2014, I grew to truly enjoy driving. Stunning landscapes, sometimes straight from a Grant Wood painting, were bittersweet amidst the challenge of canvassing rural communities, often navigating unfamiliar gravel roads to find a particular farmstead.

I selfishly want to share with Lewis a beautiful stretch of Highway 151 and Highway 6 through southern Linn County, the Amana Colonies in Iowa County, and Poweshiek County and Grinnell, before hopping back on I-80 for the final hour’s drive. After discussing the proposal, knowing we have the time, we elect together to take this scenic route.

A road in rural Iowa. Photo by Jackson Menner.

Today has been clear and sunny, unlike yesterday afternoon, but I still haven’t seen any eagles. We pass West Amana and Marengo, and I am prepared to approach the speed limit change before rolling into Ladora. Out my left window, I see an eagle perched in a tree. It’s a little too late for the others to spot it, so I ask Lewis if he would like me to turn around so he can see the eagle. With his consent, I turn around on Highway 6—Grand Army of the Republic Highway—before turning into an opening to a cornfield where we have a clear view. The eagle is maybe four-tenths of a mile south of the road, in a small line of trees, a quarter mile north of Big Bear Creek.

We take our time as we regard the eagle in its majesty. After the long moment, I place the car in reverse and the wheels immediately start spinning. Only then do I realize we are in a muddy patch. Even after lightly rocking the car, shifting between forward drive and reverse, it’s clear that we’re stuck in the mud.

My personal car is a 15-year-old Toyota Camry, which drives well, but for my trip with Lewis, I am driving a union-made Ford Fiesta, a compact rental. This choice is based on optics. Not driving a non-union-made vehicle might be considered an unforced error. My Toyota might not have gotten stuck in the same way or maybe it might have; a Fiesta is certainly smaller than a Camry.

Reflecting on the events that led to this moment, I come to terms with the fact that I made the wrong choice. Why did I wait until we were within reach of the finish line, in more ways than one, to throw out the book? Why had I let my guard down with only a marginal buffer, when I still had a two-hour drive? Even though he is a senior-level surrogate for the campaign, why did I defer to him, let alone encourage this whimsical diversion when it is my responsibility to transport him from event to event, completing the itinerary as planned? There are no answers, but I need to act.

The chief of staff and I step out of the car and assess the situation. We are in it, so to say. Some people carry kitty litter in their car trunk for added traction, but in the rental car, who am I fooling? We’re on our own. Thinking on the fly, we rip some tall grass from an adjacent stream and try to set it under the wheels. This, too, proves unsuccessful.

A muddy patch near a stream with a bridge. Photo by Jackson Menner.

East of where we’re stuck is a farmhouse, where I can see two individuals standing out back. I jog the quarter mile to the house and approach the men, who are around my age. I wonder to myself: can I plead my case?

“Good afternoon!” With all the false confidence I can muster, I explain that “I ran from over there,” pointing down the road, “because my traveling companions and I are stuck in that field. You probably know that it’s Caucus Day, and I’m traveling with Martin Luther King Jr.’s best friend, John Lewis, who is campaigning for Hillary Clinton.”

Even if I wanted to be coy, I can’t disguise my political affiliation because I am wearing a mud-caked jean jacket emblazoned with the campaign logo. “I’m stupid,” I continue, “and I thought it would be a good idea to pull off the road so we could look at a bald eagle sitting in a tree. I grew up in Grinnell, so I’m at least familiar with this stretch of highway. But we’re stuck in the mud.” And with my best hard ask, “Do you have a truck with a chain, and will you help me out of the mud so Martin Luther King Jr.’s best friend can be on his way?”

Painfully direct, I suppose. Leaving no stone unturned, I also ask the men if they’re planning on caucusing that evening. Once an organizer, always an organizer.

My mind is racing, and I’m winded from jogging down the road. I know better than to keep rambling, so I stop talking and catch my breath. The gentlemen say “yes.” They have a chain and will try, at least, to get us out of the mud.

To my second question, regarding the caucuses, they also reply “yes.” The first shares that he’ll attend the Democratic caucus where his first-choice candidate is Bernie Sanders. The second shares that he will attend the Republican caucus and that he’ll cast his straw poll ballot for Donald Trump. Despite our different political affiliations and candidate preferences, I’m reminded that these neighbors are generous and engaged. They grab the chain and hopping in their truck, we drive to meet back up with Congressman Lewis and his chief of staff.

On my return, Congressman Lewis is in the car, having called-into his two-thirty radio hit. He waves to our rescuers but is unable to say hello. The chain is quickly attached to the car, and the Focus is promptly freed from the mud. Lewis doesn’t have to leave the car at all.

As the saga in the mud has unfolded, I have stayed in touch with Secretary Vilsack’s staff and my colleagues at state headquarters, keeping them up to date on the quickly evaporating time buffer, which has deteriorated into a thirty-minute delay. I commit to my colleagues in Des Moines, for what little it’s worth, that I will get to Des Moines as quickly and safely as possible.

A countdown board displaying ‘Zero Days Until’ the Iowa 2016 Caucus from inside a campaign office for Hillary Clinton. Photo by Jackson Menner.

I’m covered in mud, and even though we’re increasingly behind schedule, I need to clean up. Once again, I ask the Congressman if we can make a detour. My plan now is to continue west on Highway 6 for the remaining thirty miles to Grinnell, where I will run into my parents’ house and change into an appropriate outfit that I think is in the house. There are no objections.

We pull onto Ninth Avenue, nearest to the side door of my parents’ house. I share that my mother is likely home. Actively working to salvage my reputation, I ask Congressman Lewis if he would like to come into the house while I clean up.

While he is grateful for the invitation, Lewis insists that he will only come inside if I first ask my mother for her permission. I sprint to the house, quickly asking for her welcome. “Of course,” she says—no other reply is possible—and I run back outside to again invite Lewis and his chief of staff inside. They sit in the living room with my mother and her brother, my uncle, who is visiting from California. Both have been volunteering for the campaign in the days leading up to the caucuses by driving in Hillary and Bill Clinton’s official motorcades.

Once I’ve changed into khakis, a sweater, and a blazer, we say thank you and offer our goodbyes. From there, I promptly drive to the Des Moines campaign office on Southwest Ninth Street. We are beyond late, but thankfully we haven’t missed Secretary Vilsack, which was my greatest fear. Secretary Vilsack says there must be a story as to why we were so late, but that is all he says aloud.

Our official commitments together complete, I remind Lewis and his chief of staff that we can visit Raygun before I deliver them to their hotel. All of us agree that it would be a much-needed palate cleanser, and we drive to Des Moines’ East Village. As at Caribou Coffee one day earlier, I see our fellow shoppers actively recognize Lewis. While people would pause briefly at the café before approaching him, at Raygun people don’t hide their enthusiasm. He takes selfies before he continues to browse. While there is no shortage of terrific merchandise, we’re all drawn to one specific shirt. We each buy matching t-shirts: navy blue with orange text, that reads “shit just got real.” Indeed, it has.

John Lewis and Des Moines attnorney Chistopher Poynor in the Raygun store in the Downtown Des Moines East Village area. Photo by Jack Menner.

I am privileged to have shared the two days with John Lewis, between very public events and mundane, private hours in the car. I continually recall the insight that while he was a towering figure in his lifelong fight for civil rights, he was also undeniably human, and someone who treated others as such. His effectiveness as an activist and a politician is rooted in this disposition. In Lewis, every moment, every interaction has embedded in it an opportunity to make a connection, hear someone out, or advance an issue. He emphasizes to me that his outlook applies to people who love you, agree with you, disagree with you, or even loathe you.

In the years since our Iowa road trip, before his passing in 2020, I crossed paths with Lewis a couple of times, but we never had the opportunity to debrief.

If I’d had the chance, I wouldn’t have sought absolution. Of course, I’d have asked the elder statesman if he ever thought about being stuck in the field with a bald eagle. More to the point, I’d have asked what he thought about the toil of working to motivate action and change, as well as the answer he would provide to the question of whether to fight the fight in the first place. Was the juice worth the squeeze? I have a hunch I know what he’d have said in answer.

In turn, if I had the chance I would have offered Lewis the following insight I gained from time spent with him: Retail politics is one tool among many, but it helps to bring about meaningful connections and the potential for action. It’s not limited to the political operative or even the political campaign sphere. Smart planning and strategy aren’t enough. Go to the people. Be with the people. Being present among others is where the magic of community is manifested, even if only toward the end of being present together.