If I ranked the significance of people who have shaped my life by the frequency they enter my thoughts, Wendell Berry would always be near the top. His writing influenced me in my early twenties when I was making decisions that would set patterns of work, family and community. I am fortunate to also have known him as a teacher and, along with his wife Tanya, as a friend. I write here to share some ways my thoughts turn to Wendell Berry.

Mud On My Boots

In the late winter, when I first turn soil in my garden to start beds of early greens and peas, I look at my boots to see if the soil is fusing in dense clumps on my soles, and I think of Wendell.

“If it sticks, your soil needs work,” he said to me once.

.](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2024-spring/strecker-1.jpeg)

Wendell Berry photo by Dan Carraco from Poets.org.

Like lots of the useful things he has written or said to me in person, this phrase is specific, tied to action (and the need for ongoing action), and indicative of a carefully developed perspective on significant topics. It is fair to say that Wendell Berry is obsessed with soil. When I took a graduate English seminar on agrarian literature with him at the University of Kentucky, some of the non-literary readings in the custom textbook he created for our course were excerpts from works by soil scientists, like F. H. King, Sir Albert Howard, and J. Russell Smith. Smith wrote a century ago about the profound ecological destruction caused by plowing by white settlers in North America, noting that the “Indian” did not destroy it. “Field wash,” he wrote, “is the greatest of all resource wastes. It removes the basis of civilization and of life itself.” 1

These thinkers systematically address reasons agriculture must be sensitively adapted to the local physical conditions and provide useful groundwork for understanding Berry’s perspective. Reflecting on his course now, I see that it sketched out a kind of literary foundation for reading Berry’s seminal 1977 work, The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture. We also read excerpts that ranged from Hesiod, Milton, and Wordsworth to contemporary agricultural writers like Gene Logsdon, Wes Jackson, and the founders of the New Alchemy Institute. We ended with an essay by the poet Donald Hall called “Rusticus,” and I wrote a paper on Robert Penn Warren, whose novel Night Rider taught me about the history of tobacco farming and politics in Kentucky.

In this way, I was further steeped in the teas of brilliant curmudgeons and thrilled by the gravitas that these writers brought to the work of farming and agriculture’s central role in culture and humanity’s survival. Our seminar of eight or so students became a close group of argumentative companions, and Wendell became a friend.

“Staring at the South End of a Northbound Horse”

I cannot remember when exactly I heard him say it, but this humorous phrase says a lot about Wendell – it is rhythmic, in the manner of a folk–saying, and admits a bit of humility.

Perhaps more than any other living writer in America, Berry is known for his defense of the use of draft animals. His reasons include the fact that the “fuel” for such “tractors” can be grown on the land they work by the farmers who work with them. Also, draft teams do less damage to a field or forest than large, heavy equipment. Importantly, working a draft team requires a relationship with other living beings and intimate knowledge of the land being worked on. Driving horses or other animals is a skill that is best learned over a long time, ideally from childhood, alongside experienced farmers.

Like Berry, my ancestral family used draft animals for traction. Like him, I grew up absorbing information about agriculture from my family - my mother and her parents and brothers - before I realized it was an education about our relationship with the land. In the acknowledgements section of The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture, he wrote:

Anything that I will ever have to say on the subject of agriculture can be little more than a continuation of talk begun in childhood with my father and with my late friend Owen Flood. Their conversation, first listened to and then joined, was my first and longest and finest instruction. From them, before I knew I was being taught, I learned to think of the meanings, the responsibilities, and the pleasures of farming. 2

An essential difference between Wendell Berry and me, a descendant of recent immigrants, is that my mother’s family was entirely displaced from our land long before I was born, so no one could “hand me the reins” when I had come of age. Instead, my relatives carried my family’s agricultural knowledge through stories and the fragmented versions of farming they continued to practice in the cramped yards in the industrial outskirts of Cincinnati, Ohio. They had emigrated from northern Greece in the 1950s to escape poverty and cultural disruption largely caused by a brutal civil war that started in 1944 at the tail end of World War II. The conflict between communists, who had organized against Nazi occupation, and the government, backed by western support, took more Greek lives than World War II and was especially devastating in northern Greece, which had been a communist headquarters. Villages and families were divided and remained bitterly untrusting for decades. Traditional community bonds were broken. Additionally, a long drought made subsistence farming all but impossible. Though they would not have called themselves subsistence farmers, that is what they were. My mom always said they were peasants. No one in her village had a tractor: oxen provided all the traction. Few people had horses because horses eat more than oxen and move too quickly to work small, rocky fields.

By the time she left their village of Aetos with her family at the age of eleven, my mother had never traveled in a vehicle faster than an ox cart. She was motion sick for the entire journey by internal combustion engine: bus to Thessaloniki, train to Athens, and freight liner across the Atlantic Ocean to Ellis Island in New York. Already skinny, she must have been gaunt at the end of the journey. I think of her as leaving an ancient culture, barely changed in centuries, and being jerked through time into a present principally defined by capitalism. Nausea seemed inevitable (and appropriate!). A cousin who remained in the village wrote to my grandmother later that the family farm dog, Mourgos, waited stubbornly at the bus stop for weeks after their departure and refused to eat. He too was sickened by their abrupt departure and by his abandonment.

Aetos weaving. Photo by Zoé Strecker.

My family’s peasant agriculture continued in various ways. Yiayia and Papou’s back yard, at the base of a nearly vertical embankment of Interstate I-75, included a row of honeybee hives, arbors of grapes, an outdoor kitchen stove, and a compost pile. They never learned to drive, having arrived in their forties, so they used that slim space between the house and the neighbor’s fence that would have been a driveway, to raise most of the vegetables they ate – beans, tomatoes, potatoes, leeks, onions, garlic, peas, eggplant, okra, squash and lots of peppers. The plants were in tight rows, spaced to accommodate just one body between them, with irrigation trenches managed by hoeing dirt gates open and closed; the hose stayed in place at the uphill end. When I traveled to Aetos in late 1987, I saw family garden plots with the same watering techniques in place, all oriented around a well that neighbors shared on a schedule, taking turns diverting the stream of water. The hoes the villagers used were short handled, like the one my Yiayia used in Cincinnati. (I am sure my Papou bought a shoulder-high American version and sawed the handle down). My uncles told spooky stories about tending the garden irrigation in the dark, when they were teenagers and their family’s turn to use the communal spring happened to be at midnight. They told tales of dares to run through the village at night with watch dogs at their heels to victoriously ring the bell in the church tower where human bones were deposited when graves were reused over generations.

To this day, the gardens in Aetos are sited close together in small plots near the edge of town where the soil is excellent due to constant additions of manure from chickens, livestock, and compost from every household. Like a medieval village, the stone houses are tightly clustered in the center with fields for crops and grazing arrayed at the outskirts. When my mother was a child, the dwelling and produce storage space were under the same roof, while a low barn in the same courtyard provided shelter for the livestock. Kitchen and work spaces moved indoors and out, according to time of year.

As Wendell Berry describes in his series of novels set in the fictional Port William, Kentucky, many tasks in Aetos were communal. For example, neighbors took turns making pasta in large batches for each household. Everyone brought their own household’s eggs to contribute for each neighbor. My mother remembers the little kids being handed sheets of fresh ribbons of dough wrapped around rolling pins. They were to lay pasta out to dry in the sun on clean sheets that were draped over straw strewn loosely on the ground. Everyone had jobs appropriate for their ages and skill sets. My great grandmother was the beekeeper and wove straw hive baskets each winter for capturing swarms in the early spring. My mother, being so young, was sent out to “shepherd” the flock of turkeys in the communal grazing pasture and told to wait to eat her packed lunch until mid-day when the sun was directly overhead and “her shadow was hidden under her feet.” Her brothers worked in the “horafia” with the older men, driving the oxen, planting, harvesting, tending; and they hunted rabbits and birds on the mountains behind the village. Women built wood-fired ovens and baked bread almost daily. They did all the cooking and food storage and made most of the cloth and household textiles from the wool of village sheep. They carded, spun, wove, knit, and crocheted the wool into rugs, blankets, and clothing. Some of the wool was dyed with vegetable materials including sugar beets, which were primarily grown for people and livestock to eat. Beets make a purple-hued red dye that has remained rich and alive, unfaded in intensity after being stored for decades in chests and now, in my own closet. Like the skills needed for driving oxen, the techniques for making and using beet dye have not been passed to me with the blankets.

Beet Dyed Aetos Weaving. Photo by Zoé Strecker.

Like Berry’s family, mine raised their own food, sources of materials for their clothing, and much of their energy. They did it within a community with long traditions that were highly responsive to their specific location. They embodied home economics as Berry describes in his eponymous book where he connects the ancient Greek root word “oikos,” or home, to the profound meaning of economics, the work that makes life possible.

I was not immersed, like Wendell Berry was, in the daily actions of my extended family and recent ancestors. Nor could I carry on practices that I only saw and heard about in fragments. But the rhythms of the work shaped me because my mother shaped me. We always had gardens and planted trees wherever we moved. And in my youth, we moved a lot; I lived in fourteen different houses before graduating from high school. My father was unstable and changed jobs repeatedly. My parents divorced when I was eleven and my sister nine. From then on, my resilient mother raised us alone. On reflection, my various family disruptions were counterbalanced by my mom’s stabilizing values and agricultural yearnings, which, in turn, drove me to stay put and make home where I am. Reading Berry’s work on the meaning of home reinforced this tendency of mine.

When I took the class with Berry, I had just graduated from Grinnell College with a degree in English literature and had come home to Kentucky to help with a family emergency. By the time things were resolved, I had already started to work as a writer and began making ceramic tiles and sculpture. My family decided to resuscitate and amplify some of the agricultural practices from my mother’s youth. My sister came back for a few years and raised a huge garden for farmers’ market sales. We were determined to intentionally shape family knowledge from Europe to our Kentucky farm by learning what we could from local people and from the writings of Wendell Berry and others. We subscribed to the Small Farmers’ Journal, and I put one of their bumper stickers on my truck that said, “Get small, go slow, mix it up and care.”

One of the first ceramic sculptures I exhibited in a professional gallery was a chess set I titled “Wendell Berry vs. Agribusiness.” Wendell’s knights were draft horses, and his pawns were hogs; the rooks were outhouses, leaning precariously. The opposing king was an agribusiness man with a ticker tape draped from fat fingers; his pawns were money bags, and his knights were drums of crude oil. (It was fan art, for sure.)

Udder-Warmed Milk, Steaming

I think of Wendell when I milk a goat or cow on a cold day, listen to the metallic sound of the hard stream against the bucket, and see the vapor rising from the udder-warmed milk.

To diversify the farm, my family got a milk cow and, later, Nubian goats. There are many hilarious and harrowing stories connected with the characters of these animals. I will simply say that I am fortunate to still have all my teeth. Milking is a difficult skill to learn without an experienced teacher. I also learned to be a midwife of dairy animals and delivered many calves and kids, including quintuplets twice. Our community was rural enough that when our mail carrier saw me struggling to help our Holstein cow, Cecilia, deliver an especially large calf in the pasture closest to the lane, he stopped and offered me the use of his soft “pulling” chains that he happened to have in his truck. He gave me some gentle advice and waited until I got the calf safely on the ground; I washed off his chains and gave them back to him before he continued with his route.

My favorite time to milk cows or goats is early on a quiet morning with the sounds of other animals chewing nearby and the smell of fresh hay and molasses sweet feed. I love when that physical muscle memory kicks in, where my fingers roll the milk down the teat to send the liquid shooting just where I aim it. Philosophically and gastronomically, it is satisfying to add more produce to the table that comes directly from our own land, fresh milk and soft cheese. And as Berry writes, and as my own ancestors knew, the livestock manure completes the circle by restoring fertility to the garden soil, proven by sticking to my boots less.

“…Our own white frozen breath hanging

In front of us; and we are here

As we have never been before,

Sighted as not before, our place

Holy, although we knew it not.”

3

Berry published this poem in 1987 in Sabbaths and gave me a beautiful broadside print of it in 1991 after I sent him and his wife Tanya a batch of sweet potatoes that I was especially proud of: huge, flavorful, and had cartoonish shapes I thought Wendell would enjoy. The broadside was printed on an old-fashioned letterpress by Grey Zeitz at the beloved Larkspur Press in Monterey, Kentucky, where he has printed many small books and broadsides. I saw Wendell in person most recently at Transylvania University, where I am a professor, for an event honoring Zeitz, poet and founder of Larkspur Press. Writers and literature lovers from the region attended the evening of readings. After Bobbie Ann Mason and Mary Anne Taylor-Hall read, Wendell took the stage and opened by saying that he thought he should be called Wendell Ann. Tanya groaned audibly from the audience and Wendell let out his infectious giggle of a laugh.

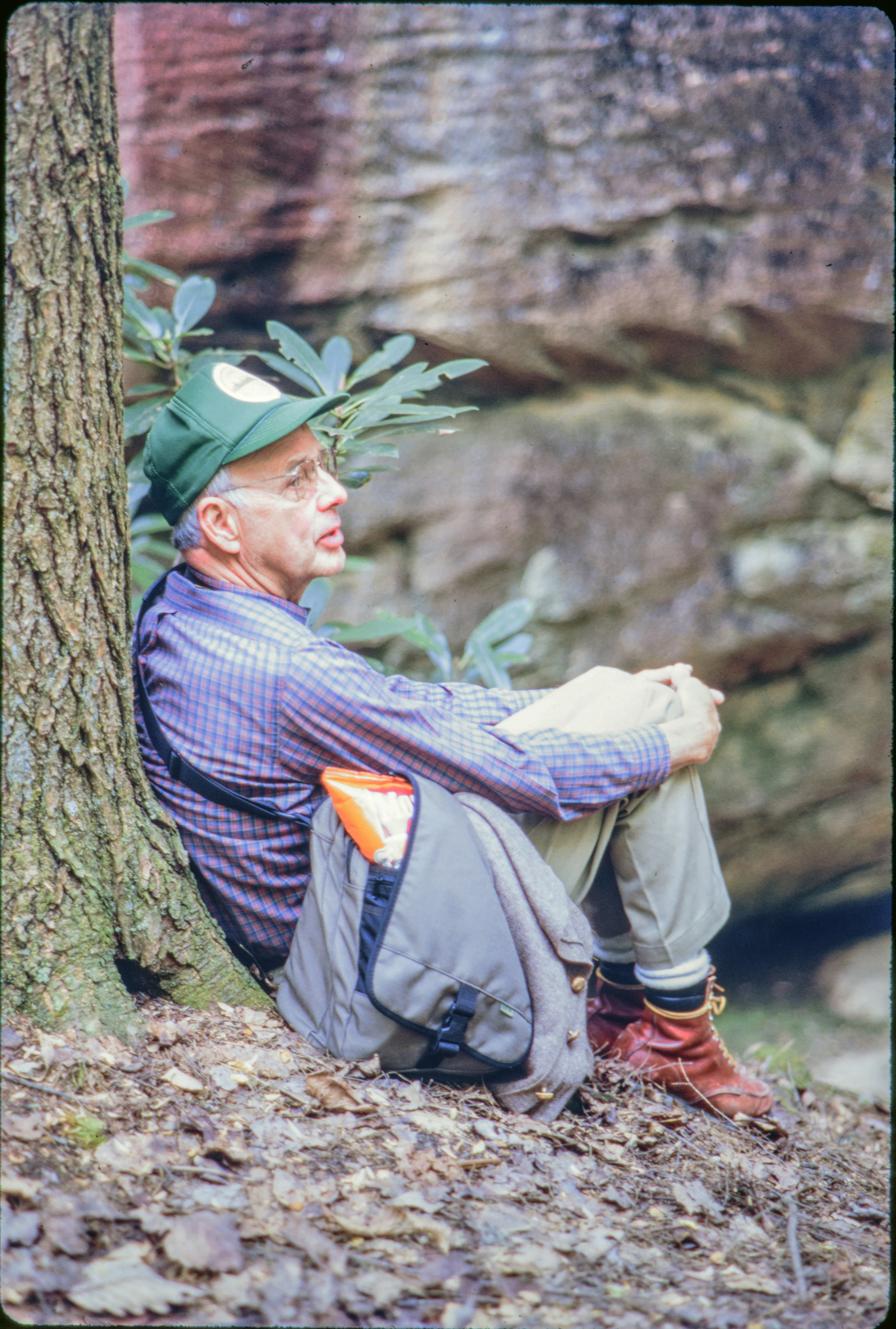

Wendell resting on a Pine Mountain hike. Photo by Zoé Strecker.

I include this excerpt from Sabbaths in part because I look at the broadside every day but also because the poem invites readers to consider the sacredness of everyday moments, and the possibility of epiphany. The poem imagines walking into a barn, a manger (if you will), and being surprised to discover Mary and Joseph and the Christ child taking shelter. The poem reminds me how much I love the quiet work of tending animals on cold, still mornings. I often think of Wendell when I see my “white frozen breath hanging,” a miracle in itself.

Looking Up from Work – Part 1

I often think of Wendell when I pause from some physical labor I’m engaged in to stretch my back. I feel gratitude for the goodness of working in the fields, among living things, domestic and wild, in the fresh air. Berry frequently writes about the profoundness of taking pleasure in the places we work and live. With close observation comes understanding and the ability to care for our places effectively. In this way, Berry helps me to make the connection between pleasure and ethical care.

Motherhood

It is an understatement to say that many topics Wendell Berry cares about – threats to family, community, wilderness, the loss of deep relationships with the land, degraded farming practices, injustice – are fraught and can lead to what he has called “ain’t it awful conversations.” After one such discussion about biodiversity loss and corporate control of land, I asked Wendell whether it made sense to bring children into such a world. His quick response has stayed with me. “Someone has to raise them right.”

In saying this, he expressed confidence that I could be that someone. It was a compliment in which a responsibility was embedded.

As a mother, I have had periods of panic about the future my daughters will inhabit. I hold Wendell’s reassuring words in my thoughts as I have tried to shape my parenting decisions around helping them become aware of their own responsibilities and collaborations with the larger living world. I also want them, and all young people, to live in a close and caring community with the people around them. Absolutely nothing feels better than “exchanges of labor and other forms of neighborliness”, 4 as Berry says of the Amish. With our immediate neighbors we have collectively helped put up each other’s hay, shared garden seeds, tools and extra produce, given eggs to each other when someone’s flock had slowed production, shared knowledge about solar energy, bee keeping, fencing, and so on. And we have helped move and retrieve wandering livestock with sticks, shouting and laughter. These informal exchanges require no record keeping – only reciprocal care. This kind of ongoing support creates a sense of security and shared responsibility that is like no other I have experienced.

Lady’s Slippers

The day Wendell told me that someone has to raise children right, we were hiking with a small group on Pine Mountain in southeastern Kentucky and had stopped to admire a rare orchid called the Yellow Lady’s Slipper (Cypripedium parviflorum) which thrives only in tandem with specific mycelium in the soil which, in turn, appears primarily in certain kinds of undisturbed, mature, healthy forests. 5 This forest is special. One of our hiking partners was the ecologist who had discovered an unusually vast stand of trees with massive crowns during a helicopter assessment of Pine Mountain a few years earlier. His ground survey confirmed that it was, indeed, a previously unrecognized old growth area. To make a long story short, shortly after our hike, the ecologist and a group of friends and colleagues with an unusual set of scientific and legal skills started planning a land trust to preserve the Blanton Forest. They succeeded, and the organization has evolved into a nationally respected conservation non-profit called the Kentucky Natural Lands Trust (KNLT). To date, KNLT has protected almost 16,000 acres of wildlands and collaborated with other organizations to protect almost 35,000 acres, many with world-class quality biodiversity and climate resilience. 6

Wendell smelling a Yellow Lady’s Slipper. Photo by Zoé Strecker.

The precarious Lady’s Slipper has served as one of KNLT’s signature species, along with Indiana bats and archaic Hellbender salamanders, all of which require extensive, healthy old-growth forests to survive. Both Wendell and I have been involved in various roles over the years supporting KNLT. Currently he is an official advisor, and I am a member of the Board of Directors.

One branch of our work, KNLT work, involves engaging artists in various ways. We make efforts to catalyze conversations about how we all might promote conservation through our creative work. Every year, we share a book Wendell Berry published in 1971 called The Unforeseen Wilderness: Kentucky’s Red River Gorge. 7 It is a poetic essay with sophisticated black and white photographs by Ralph Eugene Meatyard, that helped raise public awareness of the 26,000-acre gorge at a time when Congress had approved damming the Red River for flood control. The book was part of an important movement to prevent the destruction of this unique wild place, now a deeply beloved state park and national forest that draws rock climbers and hikers from around the globe. For artists, Berry’s book demonstrates that our work can engage with environmental issues in deep and authentic ways, without being predictable, cliched, didactic or merely illustrative of data.

Teaching and the Work of Rigorous Generosity

As a professor, I feel responsible for my students in a way that directly parallels my experiences with Wendell Berry. When I was in his seminar, and at other times when I have gone to him for advice, he has modeled how to be supportive and rigorously critical in the same gesture. He shows me how to improve my work and implies that I am capable of that improvement. I am eternally grateful for how his instruction continues to shape me; I consciously attempt to echo that constructive approach to education in my engagement with students.

In my work at Transylvania University, I have assigned his poetry, essays, and fiction in a wide variety of classes. I teach studio art and use his work to address the importance of craft. I have taught special topic travel courses that introduce students to the devastation of mountaintop removal coal (MTR) mining. I immerse students in healthy old-growth forest, and we walk the same trail I walked with Wendell on Pine Mountain. We cook by a fire and walk with botanists who know the ecosystems intimately. We explore details of individual organisms, look closely, and make artwork about our observations. My aim is to help the students become curious about—and ideally fall in love with—the greater natural world in a meaningful way. I hope they see themselves as part of the living web. In the MTR course, I exposed them to the horror of massive mountain top removal surface mines. We watch and feel the dynamite blasts and collect toxic water from the ruined streams. We listen to stories of local people whose lives and ways of living have been destroyed. Berry is a guiding voice in our course, a voice that comes from and speaks to Kentucky directly. The quote below comes from an essay I assign:

If Kentuckians, upstream and down, ever fulfill their responsibilities to the precious things they have been given – the forests, the soils, and the streams – they will do so because they will have accepted a truth that they are going to find hard: the forests, the soils and the streams are worth far more than the coal for which they are now being destroyed.

Before hearing the inevitable objections to that statement, I would remind the objectors that we are not talking here about the preservation of the “American way of life.” We are talking about the preservation of life itself. And in this conversation, people of sense do not put secondary things ahead of primary things. Those precious creatures (or resources, if you insist) that are infinitely renewable are being destroyed for the sake of a resource that, to be used, must be destroyed forever. This is not just a freak of short-term accounting and the externalization of cost – it is an inversion of our sense of what is good. It is madness.

And so, I return to my opening theme: it is not a vision of the future that we need. We need consciousness, judgment, and presence of mind. If we truly know what we have, we will change what we do. 8

PolliNation and Ditch-Digging

I think of Wendell this afternoon as I re-dig a ditch around a rectangular field that I am preparing to plant with seeds and seed bombs from thirteen species of native perennials whose leaves, flowers, and pollen will attract and support wild pollinators. This is an ongoing artwork called PolliNation. 9 The flowers are approximately red, white and blue, and I will plant them in the shape of a thirty by fifty-seven-foot American flag. I’ve followed the Xerces Society’s guidance for preparing ground for planting wildflowers and had the plot under heavy clear plastic (recycled from a high-tunnel greenhouse renovation at Berea College last spring) so the sun heated the ground and effectively burned all the existing grasses and plants without turning the soil for the last eight months. Today I am untucking the edge and rolling back the plastic, then staking out the neat stars and stripes. Next year when the thirteen varieties of plants emerge and bloom, they will resemble the flag. But in the following years I am confident the lines will blur, and the colors will mix. In a very short time, the leaning plants, wind, seed-eating birds, and spreading roots will reshape the flag, first softening its form, then obliterating it entirely. Ecological borders are more durable and meaningful than political borders. Wouldn’t it be a radically different world if we named our communities by their pollination patterns (or watersheds or soil types)? I thought of Wendell when I titled my work PolliNation, thinking he would appreciate the gesture, the critique of nationhood. More than any author in my reading orbit, he has written powerfully about the failures of our government to function as if human health and environmental health are interdependent. He criticizes all governments that hold capitalist values more dearly than any others, forcing us to “soil our own bed,” something no healthy animal will do.

The author’s PolliNation seeds. Photo by Zoé Strecker.

Looking Up from Work – Part 2

It is 51 degrees Fahrenheit, insanely warm for January 11th, too warm. Globally, 2023 was the hottest year on record since records have been kept. Before today, in central Kentucky we have had exactly one dusting of snow so far this winter. I take off my coat and keep digging my trench in the pasture between our fruit and nut tree orchards. In the field above me is our array of solar panels which power our home and two studios and charges the little electric car in which I commute to work. (…I’m driving on sunshine!) Wendell and Tanya have also installed solar panels at their home, continuing their practice of making the energy they use on their farm. A recent photo of Wendell in circulation shows him smiling and holding his fingers in a peace sign in front of their array. As I wrote above, I take every opportunity to appreciate the joy of working outside, breathing the same air as my trees, the wild birds and deer, and I think of Wendell doing the same. However, as nice as it is to enjoy working without a coat in January, this is more evidence that climate change is wreaking havoc.

Decades ago, Berry articulated the fact that climate change is a crisis that anyone can recognize, even without specialized tools. In his provocative and controversial essay “Why I am Not Going to Buy a Computer,” Berry writes, “Why do I need a centralized computer system to alert me to environmental crises? That I live every hour of every day in an environmental crisis I know from all my senses. (emphasis mine) Why then is not my first duty to reduce, so far as I can, my own consumption?” 10

The Pleasures of Eating

“Eating is an agricultural act.” 11

This powerful, five-word sentence by Wendell Berry from his essay, “The Pleasures of Eating,” is painted on the wall of our local food co-operative above a set of photos of small farmers whose produce is sold at the grocer, including the dairy farmers whose milk my daughter and I have come to buy; it is the only regional milk we can buy in glass bottles that are returned and refilled. In this part of Kentucky, Wendell Berry’s influence is present in many ways. We are fortunate. He is a treasured literary artist, a courageous critic, and a source of great encouragement to those of us who have absorbed his work. I am deeply fortunate to count him as a friend and a regular companion in my thoughts.

1 Smith, J. Russell. Tree Crops: A Permanent Agriculture. New York, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1929, pp 6-7

2 Berry, Wendell. The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture. San Francisco, Sierra Club Books, 1977, p. ix

3 Berry, Wendell. Sabbaths: 1987-90. Ipswich, UK, Golgonooza Press, 1992, p. 18

4 Unsettling, p. 213

5 Barnes, Thomas, Deborah White and Marc Evans. Rare Wildflowers of Kentucky. Lexington, The University Press of Kentucky, 2008, p.137

7 Berry, Wendell and Ralph Eugene Meatyard. The Unforeseen Wilderness: Kentucky’s Red River Gorge. Lexington, The University Press of Kentucky, 1977.

8 Berry, Wendell. “Not a Vision of Our Future, But of Ourselves” in Missing Mountains: We Went to the Mountaintop but It Wasn’t There, Kristin Johannsen (ed.). Nicholasville, Kentucky, Wind Publications, 2005.

9 PolliNation living artwork project website page

10 Berry, Wendell. What Are People For?: Essays. Berkeley, Counterpoint, 1990, 170–171

11 What Are People For?, p. 145