Less than 150 years ago the bison of the North American Great Plains were nearly wiped out by European-Americans pushing west. Scholars estimate that prior to their near extinction the North American bison herd numbered somewhere between 30 and 75 million animals. 1 Bison were a keystone herbivore on the prairie; through grazing, wallowing, and depositing nutrients they acted as an important source of disturbance, contributing to habitat and species diversity. 2 They were not only crucial to the prairie ecosystem, but also to the Native cultures that relied on them for food, shelter, and materials. For the latter reason, in the second half of the nineteenth century the U.S. government actively promoted the slaughter of bison, a policy intended to exterminate Native Americans and their way of life. Drought, habitat destruction, competition from exotic species, and introduced diseases also contributed to the bison population’s sharp decline. 3 By the time preservationists focused their attention on the buffalo, little remained of the species or their habitat and bison “had become an imprisoned, domesticated species maintained only by the constant intervention of human keepers.” 4 In 1889, North American bison numbered only 1,091, of which 635 were running wild and unprotected; 5 the wild population further declined to 325 in 1908. 6 Since then, through the efforts of private individuals and the government, bison numbers have slowly been building up again. By 1914, the American Bison Society counted 3,788 ‘North American Bison of pure blood’ in its census, a near 100 percent increase from 1908. 7

Today, the bison population has grown to an estimated 500,000 animals living in North America. Most are raised by private owners; less than 30,000 are in public herds, and of those less than 5,000 are free-roaming, unimpeded by fences. 8 9 Like the prairie itself, bison exist in mismatched patchworks, tended by a diverse array of human managers. Most bison in the United States now occupy the western plains, where less-fertile land has remained unplowed. Of the bison in private herds, over half are concentrated in South Dakota, Montana, and North Dakota.

Many people are surprised to learn that bison can now be found again in Iowa, a state more transformed from its pre-European character than any other in the U.S. Prior to settlement, Iowa was blanketed by 28.6 million acres of expansive tall-grass prairie. 10 Today, cultivated cropland alone covers 26.3 million acres of the state. 11 The industrial farmscape, divided into precise squares, is intensively cultivated with modern machinery to generate countless rows of corn and soybeans. In addition, 6.2 million cattle, 20.5 million pigs, and 64.8 million chickens now inhabit the state. 12 Bison’s return to Iowa thus juxtaposes a wild, native animal with an aggressively manipulated terrain. How, I wondered, do bison fit into Iowa’s modern agro-industrial landscape? To delve into that question I travelled around Iowa during the fall of 2011 interviewing the managers of ten bison herds.

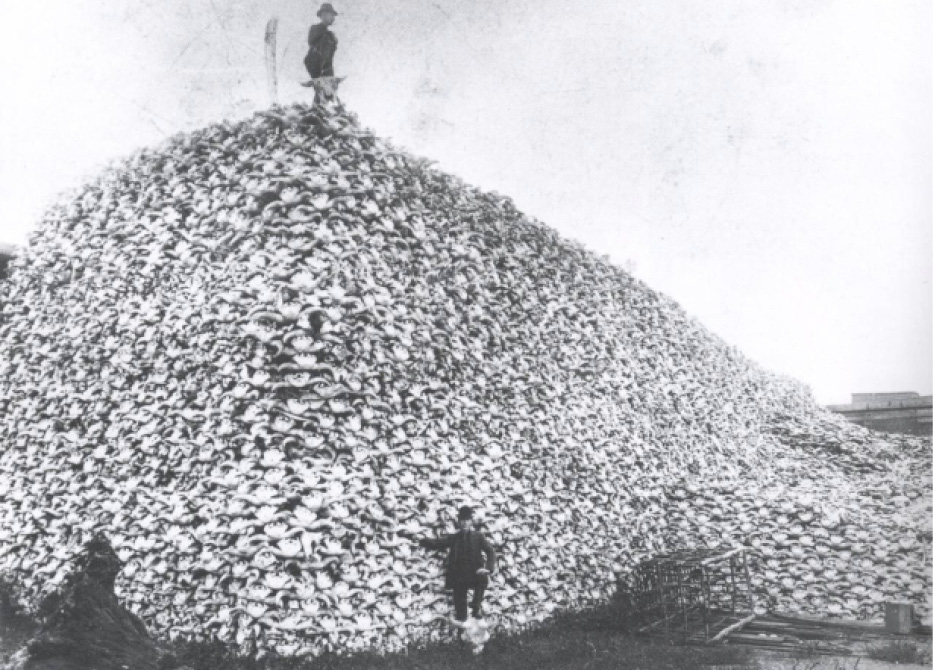

Euro-Americans killed bison in large numbers, using their meat, hides, and bones for various purposes. However, bison were also hunted purely for sport and to reduce their availability to the Plains Indians. This undated photograph of a pile of bison bones, almost certainly from the late nineteenth century, was taken at the Michigan Carbon Works in Detroit, Michigan, by J. Klima. The original is held by the Detroit Public Library.

All of the managers grew up or currently live on farms but have diverse approaches to managing bison. (To protect the anonymity of interviewees the names in this account are pseudonyms.) Diane 13 manages a 91-member herd at a federal wildlife refuge, and Darci 14 cares for seventeen bison at a tribal refuge. The remaining managers own private herds. Doug and Connie 15, a middle-aged couple, have a herd of 230. Dave, his wife Sarah, and his adult son Jake 16 manage a herd numbering 300 on their native and reconstructed prairie. Lee 17, in his 80’s and respected by other managers for his many years of experience, manages 64 bison. Lon 18 keeps careful watch over his 50-member herd and is proud to share his childhood passion for bison with his six-year-old daughter. Others have 25 or fewer bison. Brothers Tim and Will 19 milk cows and raise organic livestock and crops in addition to their bison herd, and Mark 20 mainly has crops and other livestock–bison are not his main enterprise. Art 21, at age 78, enjoys his bison and his Hereford cattle, and opens his herd to the public for tours and hunts. Frank and Deb 22 both work full-time off the farm, and in their interview said that raising bison is their hobby.

As I conducted interviews, I soon found I was dealing with a unique breed—and I don’t just mean the animals. I encountered dedicated managers who are deeply passionate about bison. I found that bison do still fit into Iowa’s landscape, in the niches carved out and preserved from conventional agricultural techniques and industrial mind-sets. They survive in the state due to a unique system that crosses wildlife management with alternative agriculture and takes a ‘nature knows best’ tactic; such a system exists not only because managers respect bison’s prairie origins, but also because bison’s inherent traits make them incompatible with industrial agriculture. These surprising attributes— their strength and speed, social interactions, ruggedness, and biology—have captured managers’ imagination and respect. In what follows I report what I learned from these men and women about the habits of bison and how they fit into the Iowan landscape. Here, managers impart their intimate knowledge of Iowa’s bison and tell a tale or two as well.

You Can’t Outrun One

Bison are particularly striking and admirable for their size, speed, and agility. While cows can weigh anywhere between 700 and 1,300 pounds, fully developed bulls can reach 2000 pounds. 23 Lee had one bull that weighed in at 2,200 pounds. Despite their large size, bison can reach top speeds of 30-35 mph, and maintain those speeds for up to half a mile. 24 They’re nimble too; they’ve been observed clearing 10-14 feet horizontal jumps and six feet vertical jumps from a stand still. 25 But, when coupled with instinctual aggression, these traits can spell danger for human handlers. As Will said, “You can’t trust them at all.” Tim agreed, “People should be more scared of them than they are. They’re not an animal that really instills fear in you, because they seem so quiet and docile, but they’re not.” Managers take significant risks when handling bison; many told stories about narrow escapes from aggressive animals. A bison cow once chased Will, who was driving a four-wheeler at 45 miles an hour, around the pasture until he got so desperate that he bailed off the ATV and dove under a fence. Lee similarly tried to outrun a distressed cow on foot in an open pasture and escaped only because the cow made a detour into the herd to look for her calf. He rolled under the fence in the nick of time, but noted, “You can’t outrun one” and, “She’d have got me if she could have.” Doug says it’s too dangerous to be on foot in the pasture with bison:

In the open pasture, I’m comfortable on the fourwheeler, but I won’t get off and walk to the other end. No, I won’t do that, because … there always seems to be one cranky cow in the bunch. I don’t want to chance it.

As these stories illustrate, bison can be aggressive in the open, particularly when they feel their young are endangered. Yet, they can be even more aggressive when they are pushed into tight spaces or confined. While sorting cows from calves in a corral, Lon’s nephew “took a ride on a cow’s horns” with so much force that he flew through a corncrib wall. Doug retold his son’s experience with a stressed-out bison cow when they were sorting bison:

…we got down to the last couple of cows… we had them too worked up. And…my son, he went in with the four wheeler, because he wasn’t feeling comfortable even, and that one cow hooked the front of his four wheeler…she hit that and just roughed him all up and bent the front of his four wheeler up.

When confined, not only can bison harm people, they are also more likely to fight amongst themselves and gore each other with their horns.

Buffalo, when they get in confinement, when they start getting irritated, they start taking it out on each other, and they can kill each other in confinement, or they’ll beat the hell out of each other, just because they’re pissed (Mark)

.…during the round up it gets pretty exciting and you see how powerful they are and that they are really not like cattle, because once you get them confined they fight, and they are really wild animals (Diane).

The trouble is if you start crowding them… they start to spook (Deb). It’s natural instinct for them to fight or flee, and they either want to run or they’re gonna get aggressive if they feel threatened, and they start to feel threatened if you start getting them in a corner (Frank). So we just try to avoid handling them that much, just [for] safety, just so they don’t get hurt (Deb).

Photo Courtesy of Kayla Koether

They Know Who You Are

Managers say bison are socially complex and fascinating. Lon said, “I could just sit out there and watch them for hours.” Lee agreed, saying “It’s just interesting to watch the interactions in those animals, and mine are as tame as you can get a herd because I’m with them a lot.” Managers say each bison has its own personality. As Lon and I ended a visit with his herd and left his pasture, one cow followed us to the gate, and he said the cow’s mother used to do the same thing. Others have even given their bison names; Frank and Deb have named almost all of the individuals in their herd.

Bison managers also feel that their herds get to know them and can distinguish them from other people. Lee once bottle-raised a calf whose mother died, and though she is now an adult cow, “Lucky” often approaches his truck and lets him pet her. Lon described that his bison even preferred one of his trucks to the other. Frank and Deb only tend their bison together and make sure all the bison are in place before a vet arrives because they say, “The minute they smell other people they’re wary.” Darci shared:

…you get to know them, and they know who you are and everybody’s got their own personality and they know right away if they like you or not. And, they usually know if it’s one of [us] three going out there in my vehicle. And they’re ok with that. They’ll come up to the truck and stuff. And it’s nice to know that they’re comfortable enough with you.

When retelling his nephew’s accident incident with the cow, Lon said that he’d told his family not to get in the pens with the bison because they didn’t recognize the strangers and would be more likely to become stressed.

They Fit In As A Clan Of Ladies

Managers explained that bison herds are organized along matriarchal family lines. “There’s usually one boss cow or dominant one that rules the roost, you might say, and the others follow,” said Doug. Frank and Deb explained that the lead cow tops the pecking order, which is based on family ties and social interaction. A calf born to the lead cow, they noted, seems to have a higher social rank among those in its age class as well. Bringing in a mature cow from a different herd will cause social upheaval, with familial cows continually fighting the newcomer (Frank and Deb). Frank and Deb had problems trying to buy other mature females and add them to their herd, as did Doug. Doug bought some dehorned females and added them to his horned existing herd, which killed one of the ‘best’ new cows. On the other hand, Frank and Deb also said that once cows calved together they were able to establish a peaceable pecking order. “Once all the cows get bred and they all have a calf, they find their pecking order…then they fit in as a clan of ladies,” said Deb. Darci explained that females then work together to care for the herd:

If you set them up in the wild there’s a matriarchal system, they have family units… you’ve got a dominant cow and a dominant bull. The herd will follow usually the dominant cow, and the bulls will follow behind. With that dominant cow you’ll start to see aunts and sisters and everybody as a whole will take care of calves.

Diane observed females helping each other with their young during the tail-end of a birth. She saw other cows come over and help the new mother clean off her calf. Overall, Frank and Deb said, having a lead cow with a calm disposition is important because it affects the whole herd as well as human handlers’ ability to move bison without causing stress.

We Have the Same Emotions That They Have

While cows fight to establish a pecking order and control of the herd, bulls compete with each other to become the dominant breeder. Lee explained that he has four bulls in the herd, which have their own pecking order:

#1 gets the choice of the cows. You know, if a cow comes in heat, he’s the one that’s gonna service her. If there’s two or three come in heat he can’t control it all, and the others get a chance…But the lesser bulls…work that cow clear away from the herd before he tries to breed her because he knows if he’s too close to the main bull, he’s gonna get it!

In cases where dominant bulls are overthrown, managers say the bulls get ‘depressed.’ Will and Tim had an older, dominant herd bull, and a young bull. Over time, the young bull grew up:

And then one time, we realized the old one, you’d go out in the pasture, and he’d be in the complete opposite corner of the pasture than the rest of the herd. And he was big and fat and in good shape, and we noticed that different times, and then we found him dead out there (Will).

They discussed this with Lee, who said it wasn’t uncommon. “Lee said it was almost like they die of depression” (Tim). One of Lon’s dominant bulls was similarly overthrown, and Lon found that he had moved away from the herd into a separate pasture. When he opened the gate, the bull fled across the road into the sorting enclosure. Lon surmised that the bull had given up. The bull knew his time was up and wanted to get out of the herd. He has stayed out of the herd and been especially moody ever since, and Lon may have to slaughter him. Tim and Will thought that behavior followed the natural order. As Will said; “You know, years ago out on the prairie, the young bull grew up so he became the dominant one, and the old one would have been the outcast, and he’s the one that the wolves would have gotten.”

These were not the only instances in which managers attributed complex motives, understanding, and emotions to bison. Lee and Lon both related stories about herd members protecting each other from death. When Lee sold meat, he used to shoot his bison on the farm and then take them to the slaughtering facility:

…and I swear, they knew which one was going to die. You know I’d have a bunch of bulls in the yard feeding them, and somebody was always between me and the bull I was going to shoot. I said I always figured that somehow they sense who’s gonna die. I don’t know. They’re quite an animal, they really are.

Lon told the story of a thrilling hunt he had hosted; the hunter shot at the bull and dropped it, although it was not yet dead. Before the hunter could get another clear shot, the herd gathered around the bull, preventing the hunter from shooting again, and tried to help the bull up. One of the cows charged the hunter multiple times before he finished the hunt.

Doug, Sarah, and Jake feel that their herd mourns the loss of its members, and so when they harvest animals for slaughter, they move 3-4 animals into a separate pen and shoot and field dress them out of sight of the herd to minimize psychological stress, and give prayers out of respect. When an animal dies naturally, they drag the carcass into the trees but leave it accessible to the herd.

I like the idea of having carcasses out there… not just for the sake of leaving the resource out there, but also for the herd. Because… we do harvest and part of the herd leaves, and they never see them again…. [Leaving the carcass] gives them an opportunity to grieve… but also psychologically not every animal that they lose sight of is just gone…they can go back and see that there is a body there. It closes the loop a little for them (Sarah).

Jake noted that the herd will go back and sniff the carcass, and if it’s a calf, the mother cow will stay with it for a few days before returning to the herd. “It’s good to just leave them out there, it’s kind of a little funeral, I guess” (Jake).

Sarah, Dave, and Jake have been accused of anthropomorphizing their animals, but that’s not quite the way they see it. Instead, they argue that it’s anthropocentric for humans to assume that we alone have emotions. According to Sarah and Dave:

Sarah: We are, we’re totally doing it [anthropomorphizing], but I don’t think of it as that they’re human emotions, I just think that they are emotions…that we have the same emotions that they have. So it’s not that we’re trying to make them into people, it’s just saying that they’re no different than people.

Dave: They’re universal emotions.

Dave, Sarah, and Jake say that herd association is matrilineal, but that all members of the family unit care for one another and contribute to the herd’s culture, knowledge, efficiency, and survival. Sarah explained that older generations teach younger generations how to forage by showing them which plants to eat and when to eat them, as plants may grow or become palatable at different times. Foraging knowledge, she says, is especially valuable during infrequent or cyclical events like droughts and floods that drastically alter the environment and the vegetative structure. Older, experienced individuals can better equip the herd for survival under such conditions. Family members such as aunts, uncles, and grandmothers are not only important sources of knowledge, but also contribute to the herd’s success through their altruism. Sarah and Dave described herd altruism this way:

Sarah: If you have a set of genes that will produce an individual that doesn’t necessarily breed… but is more helpful… like helpers at the nest, then you’re going to have a more competitive family. You will have one that takes on the roles of making everyone else more efficient, lowering stress, [etc.]. So it’s an altruistic gene… They say… that altruistic genes will breed themselves out because they will never reproduce and create new altruistic offspring. But if you look at it as a family and…that lineage… will produce an altruistic gene, then it will continue on… If as a whole, your herd, your tribe, your flock has helpers that make it more efficient, then you will survive [long] enough to continue to pass on those types of genes or behaviors (Sarah).

Dave: So that’s what the family is. That’s why we tell people… you don’t have to produce offspring to pass on genetics

Sarah: You don’t have to look at individual traits, you can look at the traits as a whole.

Photo Courtesy of Kayla Koether

Dave emphasized that the loss of family members, then, not only causes a loss of knowledge, but also stresses remaining herd members, causing them to be less productive and psychologically “dysfunctional”. Ultimately, Dave, Sarah, and Jake believe selection and competition occurs at the family unit level, rather than at the individual level. Therefore, they strive to keep many generations in their herd (including old cows that may no longer be productive) and to foster a functional social structure that they feel mimics historic, natural herds.

They Like Rough Feed

Managers commonly shared that bison are highly efficient at converting feed to energy or body weight. They report that bison maintain their body condition with less feed, or with ‘lower-quality’ forage, than that required by domesticated cattle breeds. During the winter, many livestock are fed hay made with alfalfa, a more expensive, high-protein legume, but managers say bison don’t require such a high-protein diet. According to Mark,

They do not require the land base that a stock cow does. Buffalo eat probably 1/3 less than a stock cow will, and they survive on extremely marginal ground. In fact, in the winter, it’s not highly recommended to feed buffalo…high protein hay. We supplement with good alfalfa but most of the time the buffalo are maintained through the winter on slough grass…Buffalo maintain themselves on lower-quality hay… just mature grass. That’s what they lived on in the plains all the time…I mean, we keep body condition just as good in the winter as they are on good green grass with lower quality hay, because they just maintain themselves that much better.

Doug explained that even when he makes hay and leaves it at the edge of the field his bison will continue to “eat that grass through the snow as much as they can” and only “nibble on the hay.” Not only can bison make do with what is considered “lower-quality” forage, but as Frank and Deb explained, their metabolism seems to slow in the depths of winter. Recounting her herd’s experience, Deb said:

They pack on the pounds right now [in the fall] and we think we’re never gonna make it through the winter with the hay we have… but once Christmas gets here, they back off and they just maintain. It’s like they’re preparing for winter… By Christmas they slow down… we’re not putting out as much hay.

Diane explained that they don’t give the bison supplemental winter feed at the federal refuge: “We just let them eat on their own and they do okay. They always get thinner during the winter, so around February-March…people [start] calling, saying ‘your bison are too skinny.’ It’s normal for them to be skinny….they’re pretty tough. Darci has had a similar experience at the tribal refuge. She noted that since the tribe’s bison are treated “like wildlife,” they don’t give them supplemental feed “unless their health is being threatened.” When they do, they give them alfalfa mixture hay. She says they like it, but they can’t digest it properly. Furthermore, she said “If you [supplement their] feed…with corn and grain, they won’t eat it…. They’ll eat it if that’s all they have to eat… their system’s just not set up for it.”

Bison’s dietary resourcefulness is particularly helpful for private bison-managers; they can maintain their herd on less expensive hay and other roughage like cornstalks. Furthermore, those managers who do choose to finish their bison on grain (as cattle are conventionally finished) find bison easier to care for because bison “won’t overeat” (Lee).

If they got the grass and that, they won’t stand at a feed bunk and eat ‘til they drop. They’ll come in and eat what they want and then they go back to the pasture…What I hear, they got to get their beef on full feed a little bit at a time to get them up there or else they’ll bloat. 26 Where a buffalo, I can take him right out of a grassfed pasture and give him as much feed as he wants to eat, and he’s only going to eat what he wants to eat, and I’ve never ever had anything bloat (Doug).

You can put them on a self-feeder the first day you put them in the lot… and they’ll walk up and eat what they want and walk away, where a cow will stand there [eating]‘till she dies… They like rough feed, they like cornstalks (Lee).

On the other hand, beef cattle will gorge themselves on grain or even high-protein legumes in a pasture. It is not uncommon for cattle to bloat, a process which, without human intervention, is usually fatal.

They Can Handle Themselves

Bison, it seems, find ways to take care of themselves and are particularly suited to Iowa’s environment. Managers spoke highly of their bison’s ability to survive and thrive in all seasons with little or no human intervention. When I asked Art how he managed his bison, he said, “Well, we don’t really. It’s our feeling that they’ve gotten along for 50,000 years without us and so we’re not going to do anything.” Mark agreed, saying “They can handle themselves.” Will observed his herd’s tolerance to climactic variability:

…Even this hot summer that we had this year, you’d go down in the pasture and think they’d be in the shade somewhere but a lot of times they’ll be just out in the sun, playin’ or whatever, where they could be in the shade. You know the heat don’t seem to bother them and in the wintertime, the cold don’t bother them a bit.

Doug added his own experience with this hardiness:

I had one winter that it got cold enough that it froze, but they would still go down in that creek and paw and break the ice and get some water…They’ll find water or else they’ll eat the snow and convert it over. A beef cow, they won’t do that I believe.

Lon and Lee both reported that their bison would drink out of mud puddles or small streams when it rained instead of drinking out of the watering tanks they had installed; Lee was surprised by his bison’s ability to drink “crappy” water: “It don’t seem to make them sick. There again I think that’s still hereditary from way, way back when. They’d rather drink off the ground than out of something mechanical.” Overall, Tim and Will said their bison eat less and drink less than their domestic livestock do, but Will noted that “of course they grow slower too.”

Not only are bison relatively self-sufficient when it comes to feed and water, they are also largely disease-free, apart from a reported susceptibility to internal parasites and some problems with pink eye. Mark described their hardiness, saying, “As far as management health-wise, either you’ve got a live buffalo or you’ve got a dead buffalo. It’s just most of the time we don’t have too much health problem[s] with them.” Although a few managers like Doug and Lee vaccinate their animals, most managers don’t vaccinate against any diseases or use antibiotics. Many of the private producers stressed that their animals were ‘grown naturally’ and that they didn’t receive any antibiotics (Mark, Lee, Lon, Deb, and Frank) or hormones (Doug, Mark).

All of the managers did express concern for bison’s intolerance to internal parasites. Parasites are deposited in manure and live on grass waiting to be re-ingested for a portion of their life-cycle. Thus, extended rest periods between grazes can break the parasitic lifecycle. Tim invoked evolutionary history to explain why bison are less resistant to parasitic infestation than domesticated livestock:

My theory is that when they were in the wild, they were always moving, so that they wouldn’t’ be eating where they’d been manuring. But then when you take them and you pen them up, you know, they can’t. Whereas like the domestic animals, they’ve been penned up for centuries.

All managers, including those at work on both of the refuges, medicated against the parasites. In fact, a few private owners used less anti-parasitic medicine than the refuges, or treated animals less frequently. Other disease reports were scarce; Doug reported a nasty pink-eye infection one year, and Darci said the tribal herd had experienced a lungworm infestation due to some previous pasture management problems.

They Calve Really Well

Bison reproduce with considerably less support from managers than domesticated animals require. Bison managers don’t handle or separate cows from the herd in preparation for birth, and they almost never intervene in the birthing process itself. Diane explained that when bison give birth at the refuge, “They do it themselves, and we usually don’t even know about it until it’s over.” Private producers shared the refuge’s natural birthing strategy. Doug said, “They always say leave them alone,” and Jake pointed out that they’ve hardly ever had problems with calving:

They calve really well, you don’t have to pull calves… we’ve only had like three or four over these 35 years now that have had issues having a calf, because the calves are a lot smaller than with cattle. I mean, cattle have been raised to have large calves.

Jake reveals a crucial point; since humans have genetically selected cattle over time for size and fast-growth, cattle have evolved to have larger calves. Without human supervision during the calving process, those large calves and their mothers could die in the birthing process. Bison, on the other hand, having evolved without human intervention, have smaller calves.

The mothering process also proceeds naturally and easily. Bison hardly ever reject calves after giving birth or fail to care for them the way domestic livestock sometimes do. It is not uncommon for cattle or sheep to refuse their offspring, and in those cases managers often step in and bottle feed the baby or facilitate bonding between the mother and the offspring. As Darci at the tribal reserve noted, “Buffalo calves are very good; buffalo mothers are very good- they’re actually very protective. They will keep their calves kind of hidden.” The calves, too, seem especially hardy, a source of amazement for Lee, who said:

I’ve had calves come in December, January, just one or two. It’d be a terrible blizzard if it hurt them at all. They’re born with, I think, twice the hair that a calf that’s born in the spring [has], they’re just like a little wooly bear. And [beef] calves, they freeze their ears or freeze their tails, but a buffalo, I’ve never had that happen.

Only Frank and Deb reported a case in which they intervened when a cow had problems calving. They pulled the calf and raised it on a bottle. In that instance, the cow had been bred before she was fully mature. At the refuge, cows that have such problems die, because, as Diane says, “even if we wanted to we couldn’t do anything to help. We’d have to tranquilize her just to get near her.”

Tim and Will had calving problems with one cow, which they promptly sold. In another case, when Doug attempted to check a new-born calf, the mother got nervous and started stomping the ground, accidentally breaking the calf’s ribs, an injury which was fatal. On the refuges, intervening in such processes is undesirable in its own right as managers want natural genetic selection to take its course. Private managers share that sentiment; they don’t want that problematic genetic stock to remain in their herd and cause repeated calving problems.

It Takes Twice As Long To Build A Bison Herd

While the reproductive process requires little work from managers, bison’s slow rate of maturation constrains herd growth. In a typical cattle production system, animals reach maturity at age one to one and a half. At that age, male livestock are said to be finished and ready for slaughter, while heifers 27 are ready to be bred. In contrast, Doug explained, bison are usually not mature until age two and a half to three, when male bison are ‘finished,’ and females are sexually mature. “If they do breed too early, then that cow or heifer, she’s kind of done growing…If you give her that extra year…it builds her body frame,” Doug said. The reproductive process cannot be rushed. Bison that are bred at a younger age won’t be as successful individuals and in some cases, could die giving birth, as Diane explained happened at the refuge.

This year for the first time we found a dead bison cow… it was only a two-year-old… after looking at the skeleton… there was actually bones of a calf there too. So we think that she probably died giving birth, but it was probably because she was so young and she wasn’t quite ready for it.

Bison’s longer maturation time has important implications for building a herd and preparing animals for slaughter. As Mark summarized, “…it takes twice as long to build a bison herd as it does a stock-cow herd.” Furthermore, whereas domestics, once sexually mature, are expected to give birth once a year, bison may ‘skip a year’ as they get older. As Frank said, “Even if they skip a year, it doesn’t really matter.” Deb added, “We’re usually patient because sometimes they will [skip a year].” Lee also agreed: “When they get about so old, they start skippin’, but that’s Mother Nature again.”

For private managers, slower rates of offspring replacement translate into slower returns on investments, including not only the capital investment of buying the bison, but also the continuing expenses of feed and labor. Tim and Mark both said that raising bison was “Not a get rich quick scheme.” On the other hand, some producers speculate that bison may remain productive longer than cattle. Lee spoke about a friend in Cheyenne, Wyoming, who’d been a long-time bison producer. Though he’d had to feed them range cake 28 to supplement their diet as their teeth got bad, his bison lived for 39-40 years. Lee also said he had 20-year-old bison in his own herd that were still having calves every year. In contrast, cattle in the conventional system rarely remain productive beyond 10 -15 years of age.

There’s A Lot Of Health Reasons For It

The differences between bison and traditional livestock extend beyond their life cycle and into the finished product. Interviewees shared that bison meat is lower in fat than other meats; USDA research has shown that 100 grams of raw bison meat contains 109 calories and 1.8 grams of fat, whereas 100 grams of beef contains 291 calories and 24 grams of fat. 29 Thus, Marchello and colleagues write that bison is a “highly nutrient-dense food because of the proportion of protein, fat, minerals, and fatty acids to its caloric value.” 30 They found higher concentrations of phosphorous, calcium, iron, and magnesium in bison than in beef, although beef was higher in potassium, copper, manganese, and zinc. 31 Some managers feel the meat is healthier and therefore directly contributes to customers’ well-being. As Deb said, “You feel like when you sell it, you’re selling it healthy, to people and their children, and that makes me feel good.” Doug especially emphasized the health benefits of eating bison, which he feels have impacted not only his own life and the lives of his family, but members of his community as well.

…My wife here…4 years ago or so…when she got [breast] cancer…the doctor said if she wouldn’t have been on buffalo meat to build her body, her higher iron content and higher protein, that there was no way that she would have pulled through all the chemo and radiation that she went through…. There’s another lady…in church and her husband has worked with me in construction…but she is real low in iron…she was taking like 10 iron pills a day…she’s had a couple miscarriages, just strictly because she’s low in iron…she lost the one, and so I said… ‘just give her meat, get her on it and have her eat it if she will’… and it brought her iron content of her body back up that the doctor said ‘I don’t know what you’re doing but you don’t need to be taking these iron pills anymore’… their previous baby they lost, but now they had…one since that one. So I mean, there’s a lot of health reasons for it.

All private producers direct-market some of their meat to consumers, and report that the majority of their customers are concerned about their health. Dave said 90 percent of his family’s customers are health conscious, and Doug pointed out that some customers, especially heart patients, are unable to eat beef and pork because of the fat content, but they can eat bison. Will says many of his customers are “…interested in not only their own health but the health of the Earth.”

Conclusion

Seen through the eyes of their managers, Bison are truly remarkable animals. They are strong and fast, aggressive, social, family-oriented, emotive, and protective. Having evolved with the grasslands, they are suited to the dramatic climate and rough forages, resistant to disease, and can “take care of themselves” and their offspring. Some of these characteristics are advantageous to bison managers, who find great efficiency in taking a “hands-off” approach to their herd and letting nature take its course. Managers have to learn to minimize handling and use less medication, and they can’t confine their animals in a feedlot or rely solely on grain for feedstuff. Raising bison can be physically risky due to the animals’ inherent wildness and financially risky because of their slow rate of maturation. Given the latter, growers must think and invest long-term, getting lower production from their animals, but putting in fewer inputs.

Thus, the resulting management system radically departs from conventional agriculture. Bison do not fit inside the neat squares and clean lines of the dominant industrial farmscape; rather, they are adapted to the native ecosystems that once cloaked Iowa and sustained life here. In their wildness and self-sufficiency, they contradict that old paternal delusion of conquering and improving upon nature. It seems that in order to raise bison, managers must acknowledge nature’s framework and make compromises to work within it, rather than against it. This is certainly a different arrangement than the one conventional agriculture strikes with the natural world, and it requires a divergent mindset. Being different, however, can be a social risk- one more hazard of raising bison.

Managers acknowledge the obstacles, and recognize that raising bison isn’t for everyone. They are self-professedly “different,” and “passionate.” “Trust me,” Mark says, “it takes a special individual to want to raise bison.” Reading between the lines of bison managers’ detailed observations, we see that managers take great pleasure in bonding with their bison and speculating about their evolutionary history. Managers sense that they are helping preserve a majestic North American species. In doing so, they feel deeply connected to the historic prairie landscape as they continue to carve out a place for bison in contemporary Iowa.

Photo Courtesy of Kayla Koether

Note: All quotes from specific individuals are derived from various personal interviews with the bison herd managers that took place in Octoer 2011.

1 Arthun, Dave, and Jerry L. Holechek 1982. The North American Bison. Rangelands 4(3):pp. 123-125.

2 Knapp, Alan K., John M. Blair, John M. Briggs, Scott L. Collins, David C. Hartnett, Loretta C. Johnson, and E. G. Towne 1999. The Keystone Role of Bison in North American Tallgrass Prairie. Bioscience 49(1):39.

3 McDonald, Judith L. 2001. Bison Restoration in the Great Plains and the Challenge of their Management.Great Plains Research 11(1):103-121.

4 Isenberg, Andrew C. 1997. The Returns of the Bison: Nostalgia, Profit, and Preservation. Environmental History 2(2):pp. 179-196.

5 Hornaday, William T. 1889. The Extermination of the American Bison. Washington: Government Printing Office. Electronic document, accessed 2015, 4/19, 2015.

6 American Bison Society 1914. Seventh Annual Report of the American Bison Society. Electronic document, accessed 2015, 4/19/2015>.

7 American Bison Society 1914. Seventh Annual Report of the American Bison Society. Electronic document, accessed 2015, 4/19/2015.

8 Gates, C.C., Freese, C.H., Gogan, P.J.P. and Kotzman, M. (eds. and comps.)2010. American Bison: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

9 Defenders of Wildlife 2011 Defenders of Wildlife: Bison. Electronic document, accessed 2011, 08/28, 2011.

10 Smith, Daryl D. 1998. Iowa Prairie: Original Extent and Loss, Preservation and Recovery Attempts. Journal of Iowa Academic Sciences 105(3):94-108.

11 United States Department of Agriculture 2014. 2012 Census of Agriculture, electronic document accessed 4/22/2015.

12 United States Department of Agriculture 2014. 2014 State Agriculture Overview: Iowa, electronic document accessed 04/22/2015.

13 Estrous, the time when a female is sexually receptive

14 An ailment that occurs when a ruminant’s rumen fills with gas

15 Heifer is a term for a female which has not yet had a calf.

16 Range-cake is a high-protein feed supplement commonly used in the western states.

17 USDA 2011. Bison From Farm to Table: USDA Fact Sheet, electronic document accessed 02/06/2012

18 Marchello, M. J., W. D. Slanger, D. B. Milne, A. G. Fischer, and P. T. Berg 1989. Nutrient Composition of Raw and Cooked Bison Bison. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2:177-185. a

19 Marchello,M. J., W. D. Slanger, D. B. Milne, A. G. Fischer, and P. T. Berg. 1989 Nutrient Composition of Raw and Cooked Bison Bison. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2:177-185.