To make a prairie it takes

a clover and one bee,

One clover, and a bee,

And revery.

The revery alone will do,

If bees are few.

Many people are interested in gardening, beautifying their lawns, and environmental conservancy; however, it can be unclear how to combine these different interests for the purpose of increasing the number and diversity of native pollinators. In the spirit of the “National Strategy,” I designed and led a community engagement project which immersed locally-minded plant-enthusiasts from my Ohio community in wildflower prairie improvement. From an environmental perspective, my focus was on the change in local flora before and after the project, and the potential outcomes that shift could have on pollinator populations. From a community perspective, I focused on the importance of involving community members in the process of improving biodiversity, and increasing participants’ understanding of the conservation issues involved. Through this project I have also learned a great deal about the importance of “native-scaping,” or using native plant species to support native wildlife, through researching the species present in the wildflower blend made available to the project. Throughout the development, hurdles, and continuing follow-up of this community project I have grown as both a student and as a conservationist.

Background

Growing up in the suburbs outside of Cincinnati, Ohio, I did not have much experience with natural prairie landscapes. However, traveling cross-country, as my father’s work took him to many different states, allowed me to grow my interest in the grassy plains and colorful hillocks of the areas west of the Mississippi. After moving to Columbus, Ohio, for college, and undertaking a Master’s degree focused on wildlife conservation, I gathered life experience and a deeper understanding of my environment and its shifting challenges. North American prairie landscapes became of particular interest to me when I discovered that near my home outside of Columbus are several restored prairies in Columbus Metro Parks—natural playgrounds where families can explore nature with the benefit of clear trails and maps.

The more I learned about these grassy, life-supporting breaks in the woodlands, the more fascinated I became: How is life affected by the variety of plants in a space? How many plants or plant species are required to support a single pollinator, a variety of which were ever-present in the prairie, but not near my home? Can a person, a team, or a community create long-term change for prairies and their inhabitants? Does it really take—as Emily Dickinson suggests—just one clover and a bee?

This article describes the process through which I have attempted to answer some of these questions by more deeply understanding the human-nature dynamic and the ways our actions might positively affect pollinators in the future.

In the state of Ohio, the transformation of prairies and forests into farmland and residential properties has negatively influenced the pollinator population to an extreme extent, resulting in the extirpation, or regional extinction, of many species from their native habitat. By influencing the diversity of flora in a region through farming, clear-cutting, and other “improvement” practices, humans have inadvertently affected the suitability of the environment for pollinators and other animals (Haaland & Gyllin, 2011).

Ohio is host to several conservation-minded facilities including the Grange Audubon Center, several zoos, a freshwater mussel research station, the Ohio Wildlife Center, wetland research parks, a peregrine falcon camera site, metro parks, and the Ohio Wildlife Federation. Many of these sites offer community education programs for ongoing conservation efforts. At Battelle-Darby Creek Metro Park near Columbus, Ohio, American bison are being used to maintain a tall-grass prairie restoration project. The conservation work at Battelle-Darby Creek has consisted of the restoration of over one thousand acres of wet and tall-grass prairie in the Darby Creek region through controlled burns and seeding practices (Metro Parks, 2012, 2013). Restoration of the Darby Plains Prairie, which existed in the region prior to the American westward expansion, is hoped to encourage improvement in regional biodiversity.

Since bison are now accessible to researchers and conservationists in the Central Ohio region, park-staff educators can teach more efficiently about the role of keystone species such as bison in prairie restoration. Bison are pivotal in maintaining the health of prairies through their selective grazing and wallowing habits. Through the effective use of these large herbivores, Battelle-Darby Creek Park has become a haven for many important plants and, in turn, pollinators.

The pollinator population in North America has suffered declines due to a variety of factors, including habitat loss and disease (vanEnglesdorp et al., 2008). For example, migratory pollinators such as the Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) and Ruby-Throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris) have been greatly affected by the loss of prairie landscape, normally rich with a variety of wildflowers and grasses. The cyclical way in which pollinators and plants interact has affected plant-life as well; with fewer pollinators there is a decrease in the successful seeding of wild plants. The removal of any player in the prairie cycle will cause a “Butterfly Effect,” creating detrimental outcomes for all species in the long term.

One third of the food consumed on Earth is produced through pollination; in the U.S. alone, this amounts to an estimated $15 billion in agricultural products (Calderone, 2012; Pollinator Health Task Force, 2015). The United States of America has issued its “National Strategy to Promote the Health of Honeybees and Other Pollinators” in an effort to combat the lasting effects of habitat loss, pestilence, and disease. With approximately 75 percent of all plant species reliant on pollinators for reproduction, and with one-third of the food humans eat being dependent on those plant species, the decline of pollinator populations is tied directly to the health of the human race (Ellsworth, 2014; Dirzo et al., 2014).

Field sketch courtesy of Amanda Gray

While the negative impacts caused by urban sprawl are much publicized, there are practices which we can undertake to significantly improve our world. Humans can improve the pollination cycle through seeding of natural meadows and prairies, or through developing “Native-scaped” home gardens—the transformation of garden and yard space into natural habitats for local wildlife by planting more native plants and reducing non-native species (Sempill-Watts, 2014). These practices encourage migratory stopovers by birds, butterflies, and other wildlife, which similarly add attraction and value to the property. Unfortunately, the seed mix donated to this project was a blend including many non-native plant species. It was through learning more about the species in the mix that I came to better understand the importance of regionally appropriate plants being used in seed blends and natural control methods for preventing non-native plant proliferation.

What do we mean by “biodiversity?”

Biologist E.O. Wilson said: “Biodiversity is the totality of all inherited variation in the life forms of Earth, of which we are one species. We study and save it to our great benefit. We ignore and degrade it to our great peril.”

Biodiversity is the variety of life present within a given ecosystem. Ecosystem diversity is the supportive structure for a habitat—the variety of biological organisms in an area and their interconnected, interdependent roles in the environment (Primack, 2010). Maintaining ecosystem variety through management practices is a balancing act, requiring identification of keystone species, understanding how they help maintain the health of other species in their environment, and balancing conservation focus and potential impacts of biodiversity shift. As one species increases another may decrease due to competition for resources—creating balance can be difficult, as outcomes are not always predictable.

Everything—all life and all conditions—within an ecosystem ties together in a complicated web. To approach a biodiversity improvement project, when you perform a survey of a possible area of conservation effort, you must review not only the major players, but also the support system. For instance, if you’re working on a monarch butterfly project, you have to look for the presence and variety of milkweed plants in the area. Are there enough to support a population? Are the preferred varieties present in abundance? Is the soil healthy enough to support a variety of milkweed plants? If your aim is to promote biodiversity, then each aspect of the habitat will affect the ultimate outcome.

So why is biodiversity important? Contrary to Emily Dickinson’s lovely lines, above, I believe that making a prairie takes more than “one clover and one bee,” What would happen, for instance, if the species of clover mentioned in the poem were to fall victim to a specialized fungal infection, or if especially harsh weather conditions struck, and the clover died off? In such a situation, there must be a habitat support system in place to ensure the survival of that bee and its brethren. We depend on pollinators to help us manage crops and ensure bountiful harvests, that means that losing a pollinator species within an agricultural region will, eventually, haunt the human race. There is a growing movement within the agricultural industry to mitigate the potentially negative effects of “monocrops,” or single species plantings, by surrounding farm fields with a variety of seeded wildflowers to support pollinator populations. In some states, transportation departments are also seeding wildflowers along the grassy edges of highways and roadsides to encourage pollinator habitat.

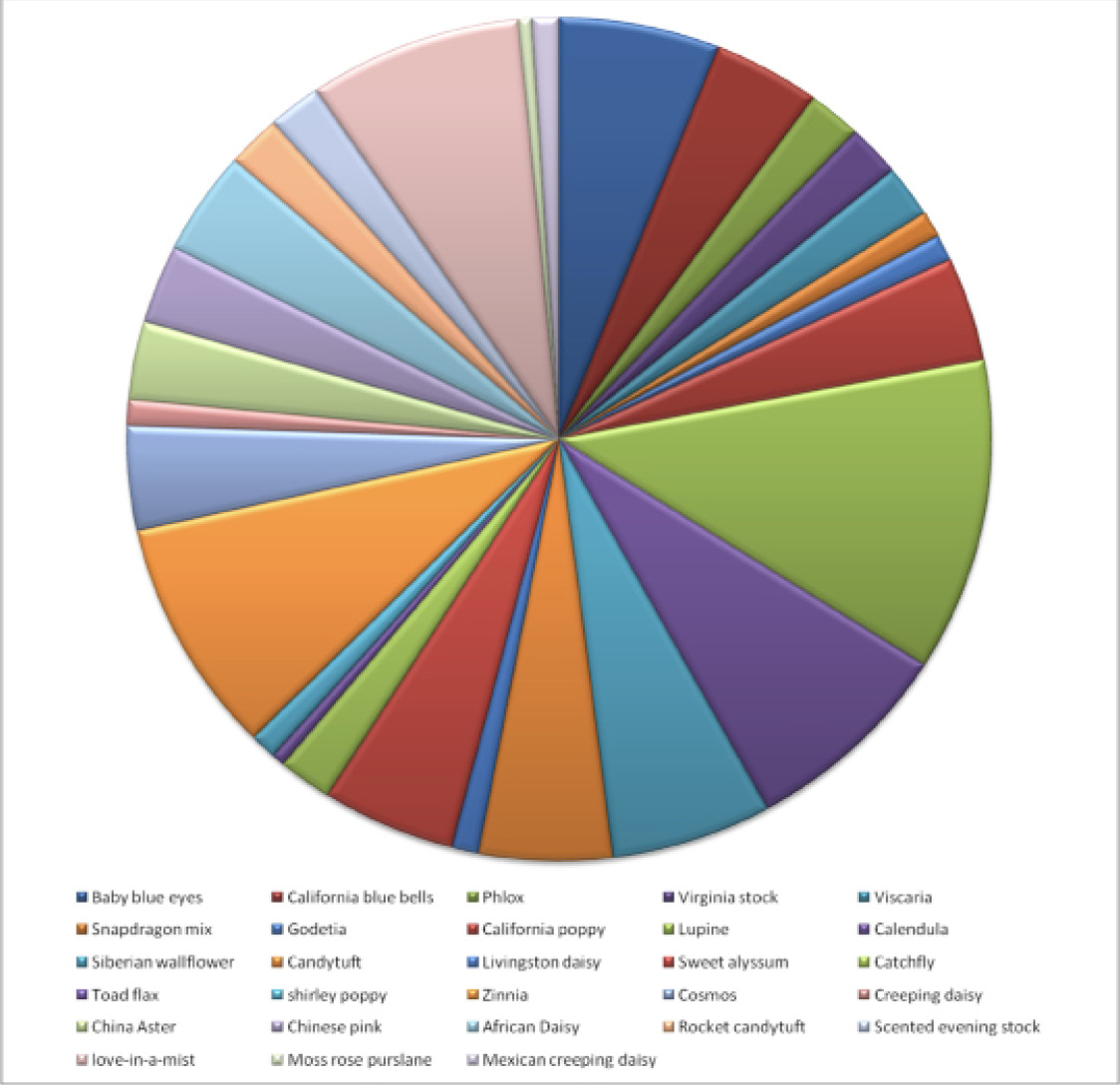

Figure 1: composition of seed mix

The Project

To improve pollinator and wildflower biodiversity in my little corner of the earth, I led a team of ten community members, including neighbors, friends, and coworkers, in an excursion to a 250-acre registered tree farm in Licking County, Ohio. This property, owned by my husband’s family, is close to our hearts: we lived there as caretakers after completing our undergraduate degrees. There are several habitat types on the property, including tall-grass prairie, a pine and hardwood forest, and a five-acre lake.

Image 1: Sowing the field

On a brisk, but sunny, early Spring morning, my team gathered over hot coffee and donuts and listened intently as I instructed them on the importance of pollinator habitat and the effects of habitat destruction. The Ohio Prairie Association has many excellent FAQ’s, maps, and a significant level of background information for those interested in learning more about Ohio’s prairie ecosystems; this gave me an extensive platform on which to build my educational portion. I laid out our sowing activity using mapping guidelines from Ohio’s CP42 Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) Pollinator Habitat practices, covering the entire acreage of a field in a large block.

The original purpose of my study was to learn about the impact of flower biodiversity on animal biodiversity, and to better understand the role of community engagement projects in biodiversity. The importance of native species was not something I was very focused on until I began to dive deeper into this project. A gardening firm donated a large bag of wildflower seed mix to our project. Not all seeds in the mix (Figure 1) are native Ohio species, but for the purpose of creating a diverse landscape and due to the cost limitations of this project, I judged that including some non-natives would help us to reach our ultimate goal. The location is also fairly contained, being surrounded on all sides by forest and in a small valley, which should help to prevent wind-carried seed spread. On a positive note, the seed manufacturer has since changed their recipe to remove potentially invasive varieties. I will also be performing surveys of the field to determine which plant species have been successful over time.

I gave each participant a bucket of wildflower seed mix to sow in an approximately three-acre tall-grass field (Image 1) which had been previously analyzed through photographs from the previous summer for wildflower species. My initial survey of the area showed that it is covered primarily in tall grasses with a few naturally occurring wildflowers—nine identified species. The acreage was regularly managed by mowing at the end of the growing season around mid-October. Continuing this management system will help enable this field to become a long-lasting, healthy pollinator habitat with high wildflower species diversity (Jones & Hayes, 1998).

The Numbers

Forty pounds of wildflower seed, comprising of 37 different species, was sown across the three acre treatment area (129,000 ft2) (Image 2). In this treatment area, seeds were sown at an application rate of 0.00031 lbs/ft2, slightly higher than the recommended label rate. With approximately 450,000 seeds per pound, participants sowed around 18 million seeds during this one event. The whole event took approximately two hours from the start of the educational session to the final discussion after sowing. The participants then enjoyed a day of recreation on the family property.

Image 2: Sowing area outlined in red

Considering that a germination test on the donated seed showed that approximately 90 percent of the seeds are viable, and allowing for five percent to be eaten by birds and rodents, there is potential to increase the number of wildflowers in the three acre area by 15.3 million. Sowing this volume and diversity of wildflower species has the potential to provide food and shelter for many pollinator species, and increase the pollinator biodiversity for the region, including preferential pollinator populations (Fründ, Linsenmair, and Blüthgen, 2010), and an increase by this amount may have an exponential effect in the long term. Future surveys will tell me which species in the blend were successful, which were not, and which may need removed if some of the non-natives show too much success.

Why Lupine?

Hartweg’s Lupine (Lupinus hartwegii) made up the largest percentage component of this wildflower mix. With the predicted 85 percent rate of successful germination, the potential exists for approximately 46,000 lupine plants to emerge in the spring to support pollinator populations. Previous research with a similar Lupine species, Lupinus perennus, indicates that higher densities of Lupine are more impactful on pollinator populations than a larger coverage area at lower densities (Bernhardt, Mitchell, and Michaels, 2008), which is one reason that the selected three acre area was chosen for this project.

Lupine is an important habitat item necessary for the endangered Karner Blue Butterfly (Lycaeides melissa samuelis), which has not been seen in the central Ohio region in decades. Karner Blue larvae are thought to feed exclusively on Lupinus perennis, and our hope is that planting a dense population of Lupine could encourage expansion from an existing metapopulation of Karner Blues—in Ohio, currently found only in their habitat near Toledo—down to Licking County and this new environment, creating a healthy local population (Hanski, 2011).

Changing Perspectives

Prior to this event, a verbal survey showed that most participants felt mild enthusiasm and interest in improving wildflower biodiversity. “It’s just not something I would normally think about,” said one participant, “I know it’s important, but I don’t really understand why,” voiced another. After participation and learning about the goals of the project participants showed increased enthusiasm, with several people requesting seed mix to spread in their own gardens and yards. Containers of seed mixed with growing media were distributed to interested participants.

Dettman-Easler and Pease (1999) discuss that participation in a conservation activity may raise general interest in a conservation effort and improve community outlook on conservation goals. Associating a place of personal interest with a conservation effort will also improve the outlook on goals, as community members have access to see the continuous effects of their efforts.

By inviting a small group of community members to sow seed, there is a potential impact for thousands of pollinators and many more animals, and humans, along the food chain. These ten community members showed an interest in the activity, and excitement about their ability to impact the natural world in a positive manner. Each individual had a potential impact of growing approximately 38,250 plants, each of which might support hundreds of pollinator species, which may support thousands of herbivores and millions of humans.

Next Steps and What YOU Can Do!

While the project I led shows the potential impact that a group of community members can have in a single morning’s activity of sowing seed, the actual ecological impact of this event may not be measureable for years as the flowers grow, attract pollinators, seed, and restart the cycle. Future seeding and management may be needed to encourage healthy prairie growth and control of the non-natives present in the field. Healthy growth, development, and reproduction of these plants will depend on weather, regional suitability, and pollinator presence. These surveillance activities offer an additional opportunity to involve community members in the prairie development process, and will be a fun challenge to undertake!

Future work on our attempt to establish this rare species in an expanded habitat could include a survey of larvae on the site after seasonal reoccurrence of lupine in the field. If you are interested in creating your own lupine habitat you can order Lupine perennius seed from prairie nursery sites such as the one you’ll find by following this link.

Image 3: Wildflower update

Supporting pollinators supports crops for human consumption, and increasing prairie biodiversity helps to restore natural balance to the prairie landscape. If individual community members take a small amount of time out of their weekends to sow seeds, plant local flora, and support pollinators within their own backyards, wherever those may be, the impact may be evident sooner than previously thought possible.

Image 4: Wildflower update

The change-effect potential of a small group of community members is astounding, and there’s tremendous potential for natural-landscape restoration programs to have dramatic positive effects in our communities. Anywhere there exists a vacant lot, a field left fallow, or a high maintenance roadside green space, there is potential for a pollinator oasis which will ensure a future for an indeterminate number of species.

If you know of an opportunity in your community to improve habitat for pollinators, I encourage you to talk to your neighbors, community boards, and local businesses to gather support for a restoration effort. Pull together your research from the articles mentioned here, and online resources such as: the American Prairie Reserve, the Prairie Nursery, The Pollinator Partnership, and many others. While “one clover and one bee,” may not be enough, one person and one community can make a difference.

Special thanks to Dr. T. Lewandowski for her assistance on this effort and to the Sinsabaugh family for their continued stewardship of the land. See the Endnotes for a list of Amanda’s references.