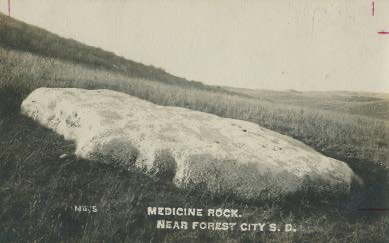

The Medicine Rock is a mystery that has existed for millions of years. South Dakota is not a place where one expects to find huge boulders sitting next to a river, yet that is exactly where the Medicine Rock was found. The rock measures about eighteen feet long by ten feet wide 1 and weighs an estimated forty tons. Originally found near the mouth of the Little Cheyenne River—where the town of Forest City was founded in 1883— the rock appears to be a glacial boulder deposited by ice when the glacier moved south from northern North America. After dating fossils found in samples taken from it in 1994, geologist Richard Hammond stated that the rock had been formed elsewhere but had settled in South Dakota between 350 and 400 million years ago. 2 Nonetheless, Hammond’s explanation doesn’t quite account for the footprints, handprints, and bear tracks embedded in the outer layer of Medicine Rock.

One theory of how the Medicine Rock’s prints were formed is a simple story passed down orally from generation to generation. A bear chased the Native American man towards the Missouri River. He came across a large rock and tried to escape by running across it. The belief is that as the man ran across the rock, leaving his footprints and handprints embedded for history to see, the Great Spirit picked him up and rescued him from the bear. Thereafter, the Dakota Sioux would put sacks of herbs and medical poultices on sticks surrounding the rock, believing that the Great Spirit would cause the medicine to become more powerful. Another legend, told by Shield Eagle of Two Kettle Tribe in 1925, speaks of the Great Spirit inspiring a wise man to carve human footprints and handprints into the stone to remind the people that they were in the care of a Higher Power. 3 Still some believe that the prints were made while the ground was still soft and were preserved as it hardened like concrete. These narratives add to the mystery of Medicine Rock when held against the 1994 report, which claimed that there were “no humans, anywhere, at the time this rock was formed.” 4

The Medicine Rock has witnessed a millennia of changes. In 1743, the Vérendrye brothers might have passed it on their way up the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains, possibly making them the first white humans to visit the sacred site. 5 Later, in 1804, Lewis and Clark are believed to have passed it as well, but did not stop because “the Indians on the shore were being a nuisance at the time.” 6 The Medicine Rock was first documented by the Atkinson-O’Fallon expedition in 1825, though it is believed that earlier fur trappers passed by it on their travels. 7 On June 28th, 1864, the rock witnessed the murder of Captain John Feilner by three Dakota Sioux men, when he intruded onto their sacred land in order to view the Medicine Rock. 8 He was on a campaign with General Alfred Sully into northern Dakota Territory 9 when his life was tragically cut short. One of the most important visitors to the Medicine Rock, General George Custer—and his wife—arrived in June of 1873, Mrs. Custer later wrote about the visit in her book, “Boots and Saddles:”

“We encamped that night near what the Indians call ‘Medicine Rock;’ my husband and I walked out to see it. It was a large stone, showing on the flat surface the impress of hands and feet made ages ago, before the clay was petrified. The Indians had tied bags of their herb medicine on poles about the rock, believing that virtue would enter into the articles left in the vicinity of this proof of the marvels or miracles of the Great Spirit…” 10

Just days after visiting Medicine Rock, General George Custer and all of his men were killed by Native American at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Photo courtesy of the Dakota Sunset Museum

From the beginning, settlers who decided to live out in both Forest City and Gettysburg, South Dakota, were well aware of the sacred standing of the Medicine Rock and had questioned whether it was worth preserving. In 1889, the rock had gotten enough attention that the Secretary of the Interior requested that a Mrs. R. M. Springer, who lived near the rock at the time, take charge of the Medicine Rock and its preservation without compensation. 11 The local newspaper soon published this request, claiming “The rock is considered by government as of great value to scientists and is desirous to keep it intact.” 12 Later, in 1927, a man named O. H. Wager begged the surrounding community to start a preservation process: by this time, the rock had “lost a great deal of its beauty and value by cutting, clipping, and chiseling.” 13 In 1936, the Medicine Rock was fenced off to prevent people from defacing the sacred object more than it had already been. 14 The general consensus of the people who wanted to protect the rock was that a fence would protect it and keep it safe for decades to come. Sadly, that wasn’t the case.

Photo courtesy of the Dakota Sunset Museum

Two decades later, the construction of the Oahe Dam threatened the Medicine Rock, along with the rest of the area, with flooding. In November of 1953, just three years before the area was flooded, the Gettysburg Fire Department decided to move the Medicine Rock to Gettysburg to prevent it from being lost forever. 15 Firemen and a local mover worked together to move the Medicine Rock from its position on the Missouri River to eastern Highway 212, next to the Medicine Rock Café. 16 It was honored with a historical marker on August 21, 1954. 17 The citizens of Gettysburg tried to protect the Rock as much as possible from erosion and vandalism, but their efforts weren’t enough. With the imprints on the Medicine Rock disappearing, it was time to decide on how to further to protect the Rock. Later, in 1989, plans for a new museum in Gettysburg gave the Medicine Rock priority of place in the building’s design. That same year the Medicine Rock moved from its spot on Highway 212 to its final resting place, at the Dakota Sunset Museum. 18 Built around the Medicine Rock, 19 the Museum gave the rock its very own display room.

Today, the Medicine Rock nestles nicely in the front room of the Dakota Sunset Museum in Gettysburg, South Dakota. Behind it, a mural of the Great Spirits by the artist Del Iron Cloud depicts how the rock would have looked, in its original spot on the Little Cheyenne River. Near the rock, a case with the negative casts of the footprints and handprints offers an up-close look; on the walls hang photos spanning a hundred years that portray the Medicine Rock at different stages of its life. Although the Medicine Rock bears some scars from those too blinded by ignorance to see its history— and those whose names are permanently embedded in the rock face— the rock itself is far from ruined. It is still perfect—it has survived for millions of years fighting erosion, global warming, and humanity— and still has the power to reduce a person to speechlessness with its incredible story.

Photo courtesy of the Dakota Sunset Museum

1 Cece and Ruth Stilgebouer, “Medicine Rock,” Gettysburg, SD 75th Anniversary Book 1883-1958 (Pierre, SD: State Publishing, 1958) 30-31.

2 Dr. Richard H. Hammond, letter to Tom Killian, January 21, 1994.

3 “Gettysburg’s main historic site in need of sprucing up,” Potter County News (Gettysburg, SD)

4 Tom Killian, letter to Phyllis Wise, February 8, 1994.

5 Winifred Fawcett, Legendary Medicine Rock, 1990.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 State Historical Society of North Dakota, “John Feilner,” North Dakota Studies, accessed March 8, 2016, <www.ndstudies.gov/content/john>-feilner

9 State Historical Society of North Dakota, “John Feilner.”

10 Elizabeth Custer, Boots and Saddles (United States: Harper & Brothers, 1885), 74-75.

11 John W. Noble, letter to R. M. Springer, March 25, 1889.

12 King & Kiplinger, “Medicine Rock: The Government Will Preserve It,” The Gettysburg Herald (Gettysburg, SD), April 10, 1889.

13 O. H. Wager, “Shall We Preserve Medicine Rock?” Potter County News (Gettysburg, SD), May 26, 1927.

14 “Medicine Rock Being Fenced,” The Lebanon Independent (Lebanon, SD), July 9, 1936.

15 Stilgebouer, “Medicine Rock.”

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Winifred Fawcett, Legendary Medicine Rock, 1990.

19 Ibid.

Resources

- Custer, Elizabeth. Boots and Saddles. United States: Harper & Brothers, 1885

- Dr. Richard H. Hammond, letter to Tom Killian, January 21, 1994.

- Fawcett, Winifred. Legendary Medicine Rock. 1990.

- Frazer, David K., ed. “Gettysburg’s main historic site in need of sprucing up,” Potter County News, April 8, 1976.

- John W. Noble, letter to R. M. Springer, March 25, 1889

- King & Kiplinger, eds. “Medicine Rock: The Government Will Preserve It.” The Gettysburg Herald, April 10, 1889.

- “Medicine Rock Being Fenced,” The Lebanon Independent (Lebanon, SD), July 9, 1936. State Historical Society of North Dakota. “John Feilner.” North Dakota Studies. Accessed March 8, 2016. www.ndstudies.gov/content/john-feilner

- Stilgebouer, Cece and Ruth, comp. “Medicine Rock.” In Gettysburg, SD 75th Anniversary Book 1883-1958, 30-31. Pierre, SD: State Publishing, 1958.

- Tom Killian, letter to Phyllis Wise, February 8, 1994.

- Wager, O. H. “Shall We Preserve Medicine Rock?” Potter County News, May 26, 1927.