We arrived in Iraq under the cover of darkness. We were a large deployment group from Wilford Hall Medical Center, Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio, Texas. Many of us knew each other, but to say we were well acquainted would be a stretch. After all, Wilford Hall was the largest medical facility in the Air Force. The range of relationships prior to our deployment was all over the map, much like the range of backgrounds and hometowns that make up every military unit. We’d been trained and trained well, but would that be enough? How would we perform in a high tempo mass casualty environment? It was August, 2004, and we were entering a war zone, specifically Operation Iraqi Freedom.

We were assigned to the 332nd Expeditionary Medical Squadron located on Balad Air Base forty miles north of Baghdad. We had every function of a civilian hospital including surgical capability, radiology, pharmacy, supply, logistics, and so on, all housed under rows of canvas tents connected by one long, main hallway. Each tent that extended perpendicularly from the hallway housed a different section of the hospital. I was assigned to the Medical/Surgical Ward, which was actually housed in three of these tents.

Iraq was very different from the small Iowa town where I was raised, right down to the very soil. Iowa is known for its fertile fields while the soil in Iraq more closely resembled baby powder with a slightly tan tint to it. In fact, everything in Iraq had a tan tint to it, the sand, the tents, our uniforms, everything. The lush green rows of crops that grow in my home state were nowhere to be seen there.

Throughout my training, I’d tried to prepare myself for the wounded American and coalition forces that we might care for. What was surprising were the number of civilian and quite possibly enemy combatants that we would be expected to treat. And it was these patients that we would see for much longer periods of time. Aeromedical evacuation or “aerovac” was so efficient that we rarely saw the same American casualties for more than a shift or two. More often than not we’d return for our next shift hoping to check on the status of a patient only to discover that they had been Aerovacc’d out to Germany or even stateside. It was one of these Iraqi patients who would steal our hearts and become a ray of light in the darkness.

His name was Sajad, and he was already a resident of the hospital when we arrived. We guessed he was somewhere around four years old, but no one knew for sure. An Army patrol had found him in a local village. His leg had been badly burned and had healed in a flexed position, making it impossible to straighten. No one knew how or when his injury had taken place, but what was certain was that this little guy would never walk again without surgical intervention. Even with cultural and religious barriers, it was communicated to the boy’s family that our facility could help and they consented. He began a series of surgeries where the scar tissue that bound his leg was cut away and replaced with layers of skin from his little back. I’m not sure how many surgeries he had endured prior our arrival, but he had not yet walked.

We all enjoyed caring for Sajad. When he was coming out of anesthesia following one of his procedures, we’d hold him until he awoke and was reacquainted with his surroundings. I doubt that I’d take to the diet most Iraqis live on, but I do believe Sajad was quite pleased with what he tasted of ours, especially candy. He would devour anything put in front of him, and there were plenty of care packages to share. I’m not sure I’d ever seen a belly swell like his did after one of his binge sessions. This, as you might expect, led to the least enjoyable aspect of caring for Sajad, as he was still dependent on diapers. We finally had to hang a sign above his bed stating in large block letters, “PLEASE DO NOT FEED THE CHILD!!!”

After each surgical procedure, Sajad’s leg would be in a hard cast or some sort of splint to keep it immobilized. Walking with a bent leg was impossible, but teaching him to walk with straight, stiff leg was going to be a challenge. Someone found one of those round baby walkers with wheels that he could sit in and this worked amazingly well. Sajad was off and running. It meant he required much more supervision, but it was a joy to see a child play, especially in the environment we were surrounded by. We couldn’t help but wonder whether this was his first time experiencing this kind of freedom.

We worked on weening him away from the walker. We would often stand him up and toss a soccer ball at him. Prompting him to kick it back. This was quite effective at working on his balance and agility.

I definitely knew that many of those I was serving with were extremely fond of little Sajad. Who could blame them? He was as cute as could be. He smiled constantly and rarely fussed. One of the fondest memories I have was one of those moments when you hear a new word or words from a youngster, and know he or she understands the proper use of that vocabulary. Obviously, there was a language barrier between us, but one day I was holding Sajad and out of nowhere he gave me a big hug, smiled and said “I love you.” My heart absolutely melted.

We all wanted to see him progress, but I don’t think we correlated this with him leaving us. After all, he’d been with us for the majority of our deployment. It only seemed logical that we’d be able to keep him. Sajad’s family had only visited a few times in the more than two months he’d been with us. We often wondered if they’d abandoned him. I was so convinced of this, and was certainly so attached that I actually had my First Sergeant contact the U.S. Embassy on my behalf to look into my adopting Sajad. They made it clear that that scenario was not possible. I now believe that his family probably had transportation or financial obstacles that kept them away.

Our feelings for Sajad were never clearer than they were on the day we learned his family was picking him up. Word spread through the hospital like a wildfire. I rushed to his bed as soon as I heard. There was a group of around half-a-dozen medical personnel there, which was about half-a-dozen more than were needed, but we all wanted to say goodbye. The mood that followed was worse than anything we’d experienced to date, and we’d experienced a lot. We’d set records for the number of casualties aerovac’d out of the area of operation, so you can imagine the level of carnage we’d been exposed to. Our affection for our little mascot was clear and became even clearer a few weeks later when Sajad returned for a follow-up. Again, the news flew through the facility, and again I raced to find him. When I located him, he was surrounded by staff members and of course, eating. When our eyes met, he lit up and his big smile met mine.

There’s one memory in particular that connects the life I led in Iraq with the life I am leading today in my home town. I was one of the higher-ranking personnel in the hospital, and functioned as a shift supervisor. Those who worked for me had specific patients to care for, and duties assigned to them. I had much more flexibility, which allowed me to spend more time with Sajad, and I’d often carry him with me as I made my rounds. One day I noticed his hair was getting a little shaggy and decided a haircut was in order.

As you might imagine, this mission had a high chance of failure. After all, no one can predict how a child will behave in a barber chair, and that’s without a language barrier. Sajad seemed to trust me. I guess we’d bonded pretty well by this point, but honestly, I’m sure he was ready for a change of scenery. So, I loaded him up in the Hummvee, buckled him in the passenger seat and we were off to the barbershop. I don’t remember now if he gave me much trouble in the barber chair, but I do remember holding him in my lap as the barber did his thing, and I remember working up quite a sweat doing it. He was sure a hit with everyone we encountered that afternoon. Smiling and greeting them all, bringing a smile to their faces as well. He certainly looked sharp with that new cut and it seemed he knew it as well.

Photo courtesy of Randall Hotchkin

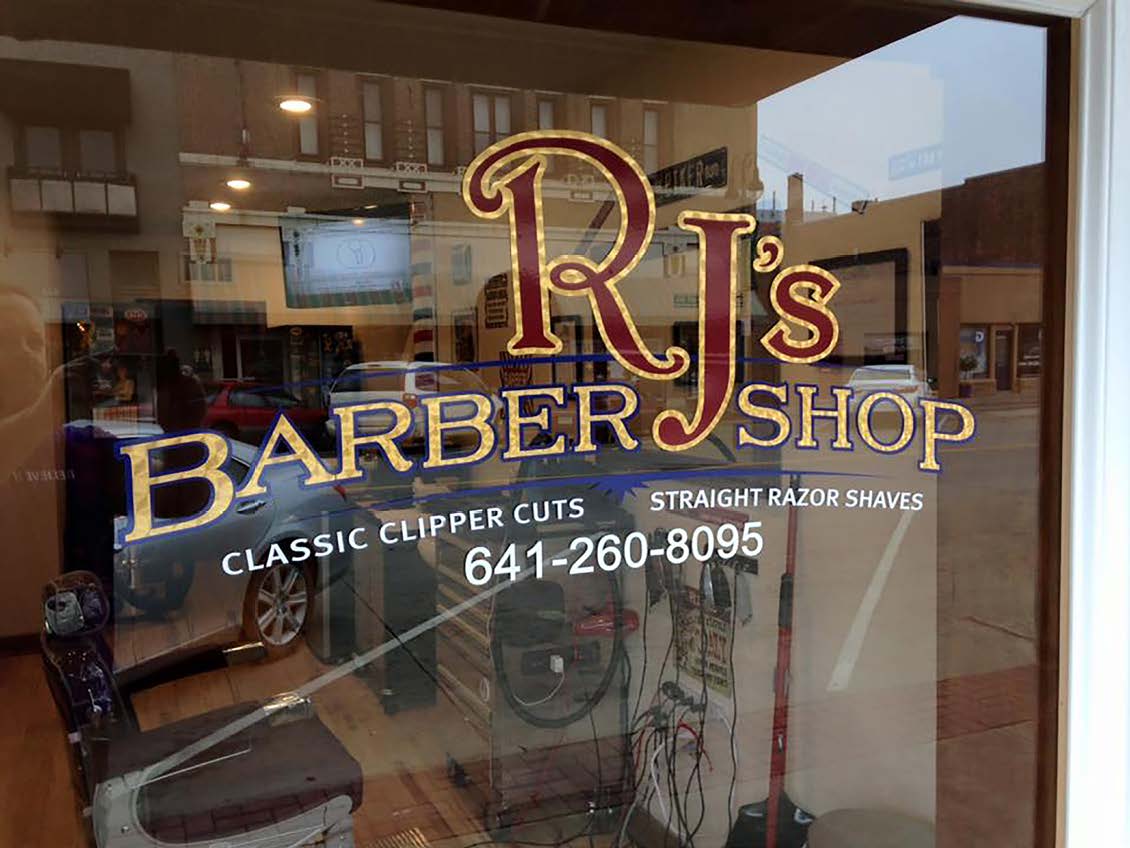

It’s interesting to note that, many years later, retired from the Air Force, I find myself back in my hometown, cutting hair in my own small-town barbershop. I had a friend once tell me that she thought it was really cool that I had joined the military like my father, and was now doing hair like my mother, who was a beautician. I’m fine with where things ended up. There aren’t many things you can do in life that give you immediate gratification from your work, but I have that privilege.

There are probably many things that shape a man and who he will become. I like to think we had a variety of missions while in Iraq but most important to me was the healing of hearts and minds. Hopefully, little Sajad will never don a suicide vest or detonate a vehicle born IED (Improvised Explosive Device). Hopefully, he shares his memories with friends and family of the nice Americans that made it possible for him to walk. In a perfect world, I imagine him as a community or national leader, working to erase the hatred that seems so prevalent in his culture.

These days I get to turn folks of all ages around to unveil their new haircut and see their initial response. Fortunately, that response is usually positive. Many times, the customer is a young boy who can’t hide the pride he feels in how he looks. Much like little Sajad on our barbershop adventure that sunny day in Iraq.