As a long-time teacher of humanities and American studies at Albert Lea High Schooland Riverland Community College in Minnesota, I loved introducing students to Thoreau and his works. When I took a graduate course on Thoreau, I already knew that he had spent most of his life in and around his home town of Concord, Massachusetts, and that his experiment in living a simple and deliberate life in the woods at Walden Pond had influenced conservationist movements around the world. Likewise, I knew that his “Resistance to Civil Government” had become a handbook for all who would attempt to bring about political and social change, including Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I was not aware, however, of Thoreau’s impact on modern architecture until I took the graduate course on his work. When I learned about his influence, I was intrigued. Many years later I was able to implement his ideas when I built a reproduction of his cabin near my home on the shores of Geneva Lake in southern Minnesota.

Like me, many readers of Walden are unaware of Thoreau’s impact on modern architecture. When he described building his home at Walden Pond in a few pages of the first chapter, he laid the groundwork for an organic theory of architecture. A century later his theories took root on the prairie through the homes designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, and Wright’s early homes were part of the Prairie School of Architecture that he inaugurated.

When Thoreau built his one room home for a total of $28.12½, he used recycled materials from a shanty and did most of the work himself. In stating that a house should be built around the inhabitants’ needs using natural materials of earth and nature’s colors so that it becomes part of the natural environment, he expressed a couple of fundamental elements of organic architecture. He also said that “all men should have the pleasure of building their own homes.” His home, a 10’ x15’ structure, satisfied his simple needs. It contained a fireplace, a single bed, a writing table, and three chairs (one for solitude, two for friendship, and three for society). His home—and he called it his home and not his cabin—fit beautifully into the natural environment at Walden Pond. He asked his readers to consider “how slight a shelter is absolutely necessary” and further stated that “[t]he most interesting dwellings in this country, as the painter knows, are the most unpretending, humble log huts and cottages of the poor community.” I suspect Thoreau would be somewhat amused and pleased by the current tiny house movement where his ideas, whether known to the occupants or not, are being implemented.

Fallingwater, the retreat Frank Llyod Wright designed for the Kaufmann family in the woods of Mill Run, Pennsylvania. Photo by R London, 2014, from Wikimedia Commons.

My newly discovered information about Thoreau’s views on architecture increased my interest in the designs of Frank Lloyd Wright as seen through his Prairie School. As a result, I toured Taliesen East in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and the Stockman home in Mason City, Iowa. The connections with Thoreau became very clear during these visits. Wright has been called an “earth son,” a description he appreciated, and one that Thoreau would have appreciated as well. The principle that “form follows function”—first expressed by Wright’s onetime mentor Louis Sullivan—echoes Thoreau’s idea about building a home based on the inhabitants’ needs. In order to do this, Wright was known to stay with a family before he began designing a home for them. Wright also believed that a building should reflect its natural environment. His prairie style houses, exemplified by Robie House in Chicago, were long and horizontal with cantilever overhangs in order to blend with the prairie landscape. Even when Wright designed homes in other parts of the county, such as Fallingwater in western Pennsylvania, he incorporated the structure into the natural surrounding; for example, Fallingwater is built around a waterfall rather than merely near it, and it reflects the colors of the rhododendron in the fall. His two architectural schools, Taliesen East in Wisconsin and Taliesen West in Arizona, were designed to reflect their native environments and use the natural colors of their areas.

Like Thoreau, Wright believed that people should learn by doing. Thoreau was amazed that he was never required to get in a boat when he took a course in navigation at Harvard, and he was determined to build his own home for his experiment in simple living. Likewise, students at Wright’s schools lived together, worked together, studied together and were expected to help with the everyday operations of the facilities, a much more practical approach than that of a typical college or university. “If you have built castles in the air your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put foundations under them,” wrote Thoreau, and Wright encouraged his students to do the same.

Learning by doing became real to me when I took a course titled “Build Thoreau’s Cabin” at the North House Folk School in Grand Marais, Minnesota, during Memorial Day weekend in 2003. The opportunity to take an actual course in building a reproduction of Thoreau’s home attracted me. For five full days, nine other students and I worked with an instructor building a cabin. It was built in a remote and wooded area rather than on campus, and the learning was hands-on. In the few times the instructor needed to give a “lecture,” he used a piece of plywood and a carpenter’s pencil rather than a power-point, an approach Thoreau would have appreciated. We learned the basic use of a carpenter’s tools as well as the means of designing and constructing our own buildings.

Two years before taking that course, I had purchased four and a half acres of woods on Geneva Lake in southern Minnesota, and the main house was constructed in 2002. The building lot was kept small in order to keep the house surrounded by woods. The house itself has a prow front with sliding glass doors facing the lake. Each door is complemented by a Wright window on each side, and the cedar siding was stained to match the surrounding woods. For Wright, an inhabitant of a home should not be able to tell where the house ends and nature begins. Now, on this lot, I had a perfect place to build a structure like Thoreau’s. The reproduction is the exact size of Thoreau’s home—10’ x 15’—but the roof has a greater pitch than his in order to allow a loft to be included; this works well when the cabin is used as a guest house. The interior is different from Thoreau’s, and the cabin is placed so that the front without windows faces the main house. The side windows, recycled from the main house, face the woods, and one of them faces the lake beyond the woods. Former students had already named my new home Walden West, and they were pleased to see that Thoreau’s home at Walden was being re-created.

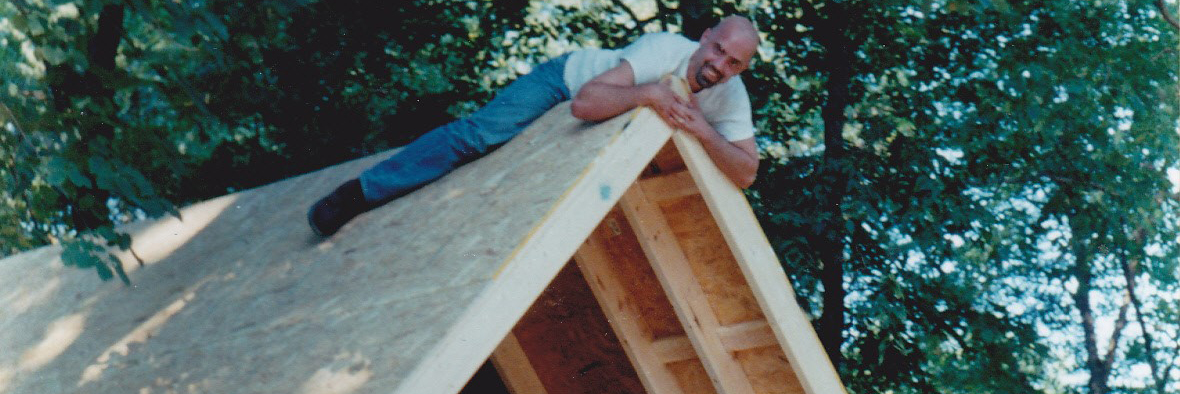

“walden on the prairie,” under construction. Photo courtesy of Paul Goodnature

I began the actual project in the late summer of 2003, and the house was framed and enclosed before the snow flew. The supplies cost about $3,000, which would be the approximate cost of Thoreau’s expenses if inflation is calculated at four percent per year since 1845. A number of graduates from Albert Lea High School volunteered their labor, so there was no cost for that element. The interior of the cabin was completed in the spring of 2004. Since that time, I have given presentations about Thoreau, his philosophy, and the building of the cabin to high school groups and community organizations such as the American Association of University Women (AAUW). Many former students have toured the cabin, and some have stayed in it with their families. The cabin has become relatively well known in the area, and the local newspaper did an article about it in 2006.

Both Thoreau and Wright believed a person needs a strong connection to place, and that a house became a home when it was designed to fit the needs of the occupants rather than vice-versa. In addition, the house itself needs to be at home in nature by reflecting the natural environment of its location. Home, then, becomes a place where a person is completely comfortable in his or her environment, and that environment is grounded and reflected in the beauty of nature surrounding the home. According to Thoreau’s and Wright’s thinking, Walden West at Geneva Lake is my home in the truest sense of the word, and the cabin has become an important part of my sense of place. Even though only parts of the original foundation of Thoreau’s home remain at Walden Pond, he now has a home on the prairie.

The author’s interpretation—located on Geneva Lake, Minnesota—of Thoreau’s home on Walden Pond. Photo courtesy of Paul Goodnature