George Floyd died in a Midwestern city, smack in the middle of the northern prairie. Stop a moment, and take that in. White Midwesterners who like me live in rural areas might until recently have been able to indulge in the fantasy that we are far in geography and mindset from the hotbeds of racial conflict that became infamous during the civil rights struggles of the 50s, 60s and 70s. We’re not (we’ve told ourselves) Montgomery, or Selma, or Memphis, or Jackson, or any of the other southern cities or towns where freedom rides, lunch-counter sit-ins and bus-boycotts took place. There’s no Bull Connor here to set his dogs on peaceful demonstrators, or night riders burning crosses on the lawns of our black civic leaders. There are no statues of Confederate generals standing in our public squares. No one has buried workers for social justice in levees here, or left civil rights icons bleeding and dying on motel balconies. That’s not us.

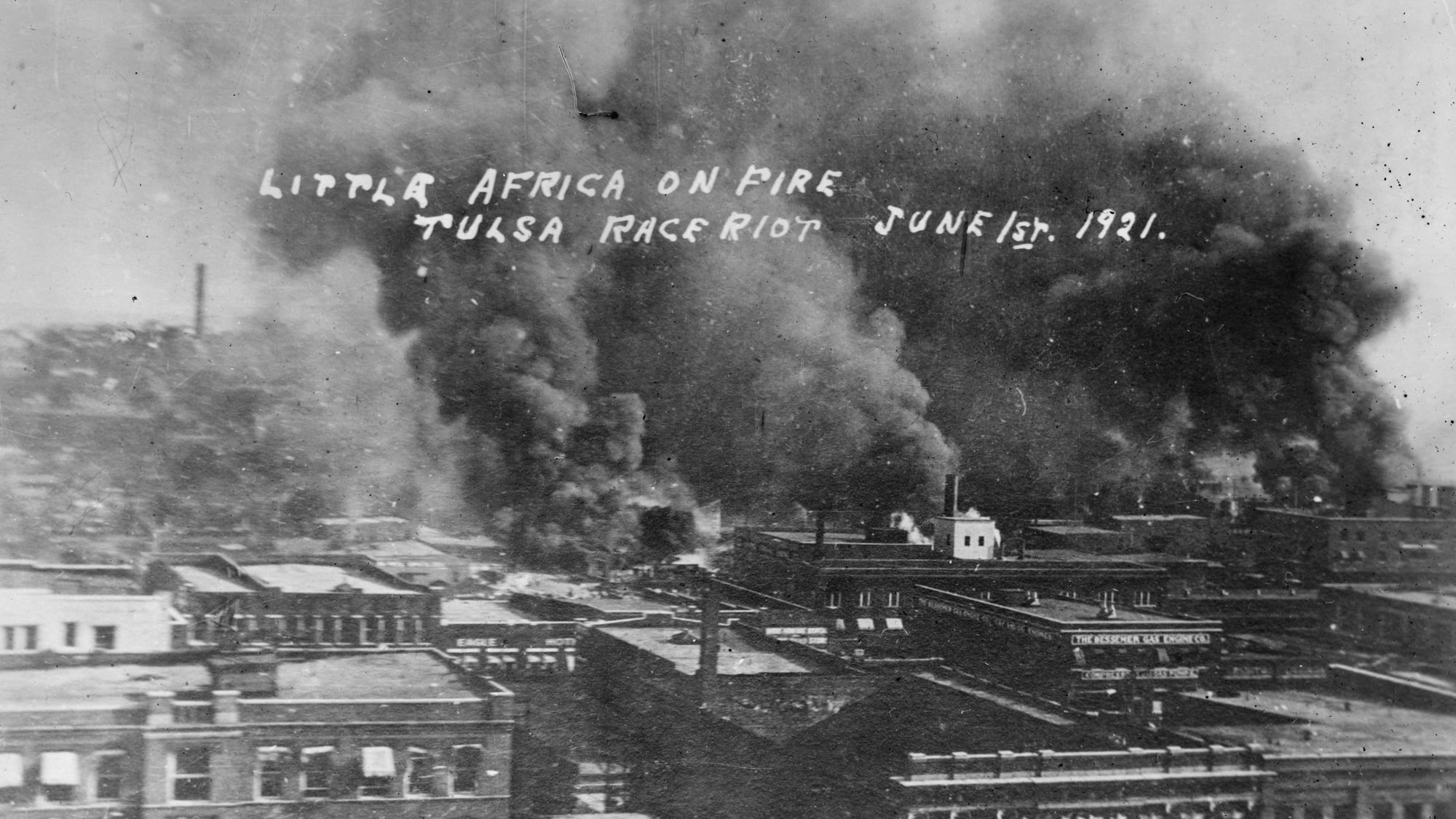

Except it is. Three of the names that come immediately to mind—George Floyd, Philando Castile, Michael Brown—are those of men who died under murky circumstances in Midwestern cities, all in encounters with white police. The worst racial violence in post-Civil War American history happened on the prairie—in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where in 1921 over 176 African-American were killed in a spasm of rage that saw the Greenwood neighborhood—then the most prosperous African-American community in the nation—put to the torch. Over 1,200 houses were burned, and more than 200 more were looted by angry white mobs. Nearly 200 businesses were destroyed, along with a junior high school, several churches, and the district’s only hospital. It was as if an entire small town were effectively wiped off the map.

We might tell ourselves that we’ve outlived those days of animus and violence—that the Midwest is better than that now. But anyone indulging this fantasy should look at the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hate Map,2 which shows that there are nearly 200 hate groups in prairie states, or have a look at a 2019 report Race in the Heartland: Equity, Opportunity and Public Policy in the Midwest, put out by the University of Iowa and the Iowa Policy Project.

The report makes for grim reading, but it’s worth the effort, and worth quoting here in detail: “[T]he rate of black homeownership [in the Midwest] has not budged since 1970, and the gap between black and white homeownership, a consequence of both generational disadvantages and the persistence of private discrimination in real estate and home finance, is now wider than it was in 1900. The accumulation of disadvantage in housing and employment over the last generation has widened a stark and persistent racial wealth gap. Across this era, the African American unemployment rate has remained at nearly double the rate for white workers. After some progress in the 1960s and 1970s, racial segregation in public schools has steadily increased. African Americans are imprisoned at five times the rate of white Americans.”

The report goes on to list in dreary detail the many ways our prairie home place has disadvantaged, disrespected and disenfranchised African-Americans, and continues to do so. More than merely establishing that the prairie region is fully participant in the national malaise of racism, though, the report’s authors cite a recent analysis of racial inequality in all the states. The report says that Midwestern states (which it identifies as Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin) “[claim] eight of the bottom ten slots and [sweep] the bottom five.”

“Simply put,” the report continues, “these stark racial disparities—and the patterns of segregation and discrimination which underlie them—create real and lasting barriers for workers and families of color in the Midwest. The consequences—for those directly affected and for our broader aspirations of equity and equal opportunity—are dire.” There are forms of violence which do not involve police batons, tear gas or bullets, but which cripple and kill just as effectively. The violence convulsing our cities as I write is only the most visible symptom of a much deeper, much more pernicious problem.

To understand the true effects and extent of racism in the Midwest, it’s also important to look at the demographics of our urban areas. In the last census, ten Midwest cities had over 50 percent of their populations made up of people of color. Another ten had over 40 percent of residents who were people of color, and the percentage of people of color living in the Midwest overall is 23.4 percent. This is why places like Chicago, Detroit, Kansas City, Milwaukee, St. Louis, and the Twin Cities are areas where people have taken to the streets to protest George Floyd’s murder in such huge numbers.

Nor are the cities the only places where the scars of racism—some old, some like George Floyd’s murder, freshly inflicted are evident. Today, on the streets of my small town in Iowa—a state which sent 76,000 troops to the Civil War to fight for the Union, of whom 13,000 died—there are pickup trucks driving around emblazoned with Confederate flags. When my neighbors and I put up yard signs several years ago, extending welcome to immigrants in multiple languages, they were often ripped from the ground, or disappeared entirely in the dark of night. And recently, as COVID-19 took hold in the country, Chinese students attending the College where I work and teach were subjected to regular harassment.

And then there is Steve King, one of Iowa’s Representatives to the U.S. Congress, who during his time in office regularly garnered headlines for saying things like “White nationalist, white supremacist, Western civilization—how did that language become offensive?” King was finally defeated during the recent Republican primary, but only after his constituents had returned him to Washington nine times. It is appallingly ironic that one of King’s committee assignments was the chairmanship of the House’s subcommittee on the Constitution and civil justice.

After we elected Barack Obama as our first black president in 2008, I remember there was hopeful speculation in some quarters that we had at last entered a “post-racial” America. But as we’ve seen amply illustrated, our reports of racism’s demise were sadly exaggerated. George Floyd died in Minneapolis in 2020. This should be our mantra if ever again we feel tempted to rest on our laurels, and to say we’ve finished the work of securing civil rights for every Midwesterner.

We need to be as good as we think we are.

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, American Red Cross national Photograph Collection. Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood is referred to here as ‘Little Africa’