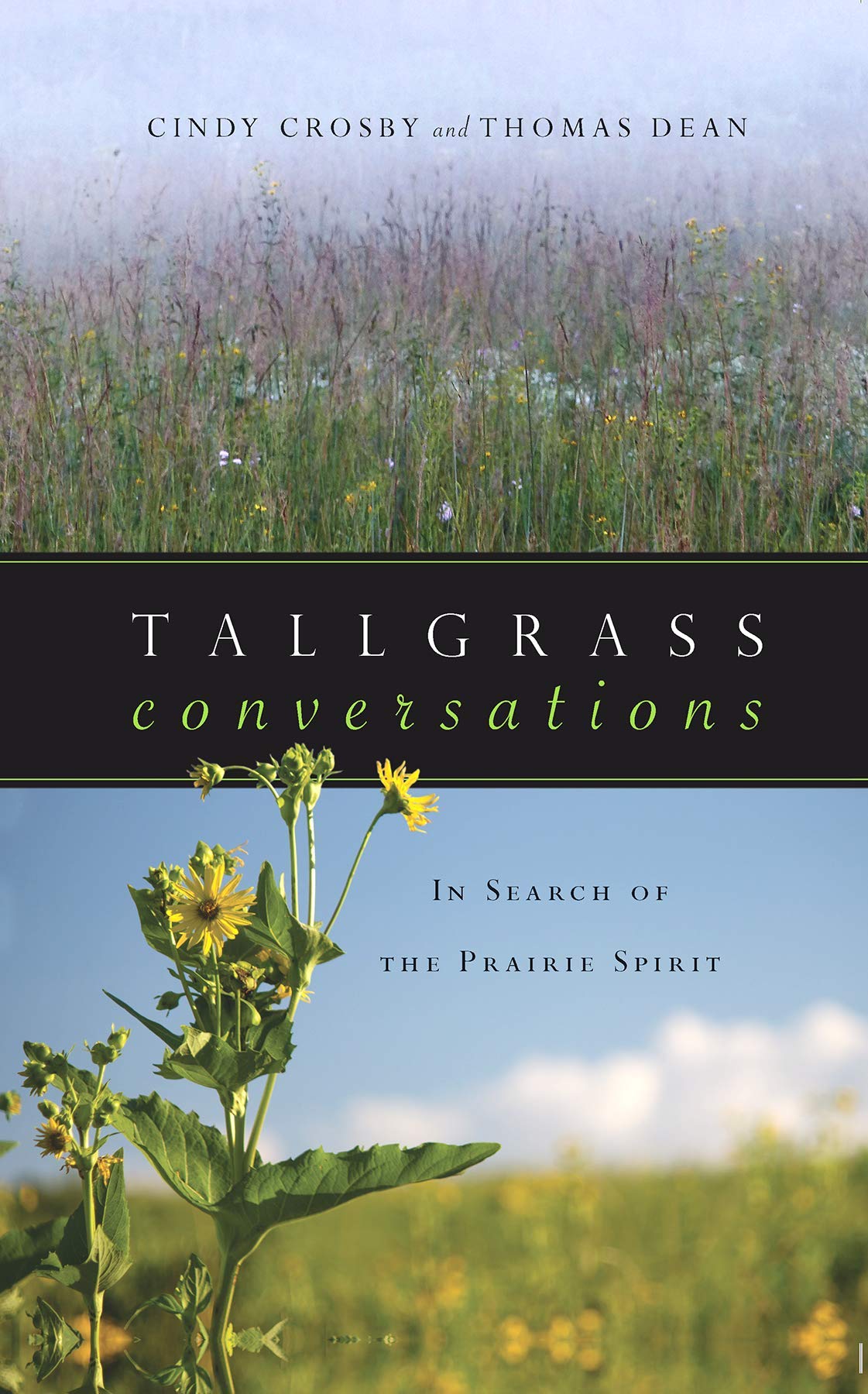

Tallgrass Conversations: In Search of the Prairie Spirit is like a series of love letters to the prairies and savannas of the Midwest. This beautifully illustrated book written by Cindy Crosby and Thomas Dean features paired essays about “tallgrass” inspired by each of their reactions to a single word. “Tallgrass” is their shorthand for prairie and savanna. Clearly, each essay in a couplet is written independently, but together, ideas spawned by their unique perspectives seem almost to dance with one another. Dean notes how the essays “converse symbiotically,” creating “…an artistic whole greater than the sum of its parts.” Crosby goes deeper, hoping to “…connect people’s hearts and minds with our prairie restorations and remnants and to prevent further loss.” She notes John T. Price’s warning in The Tallgrass Prairie Reader^^ that a lack of writing about tallgrass has presented “another kind of extinction.” If writings about prairie and savanna are scarce, few people can know, care or advocate for these rare, precious places, and they will wither. In Tallgrass Conversations the authors strive to help prevent this sort of extinction.

The book is organized into five themes, each theme beginning with “The spirit of…” and ending with a single word. The words include opening, awareness, celebration, reflection, and hope. For each theme, there are four to six “conversations” or pairs of essays, each pair relating to one of a second set of themes. In these linked essays, the authors guide us through very personal explorations of tallgrass through the lens of their own experiences, concerns, and musings. They probe the meanings of words like home, healing, remnant, joy, change and persistence to name a few, all in relation to tallgrass.

Photographs in Tallgrass Conversations add visual backdrops that echo the written theme. Printed on thick, quality paper, vibrantly colored images adorn every page, and often occupy one or two full pages. You like red? Check out Crosby’s essay on joy! The expense of this sort of presentation is rare, in books, and makes this one even more of a treasure!

Crosby and Dean rightly emphasize the value of remnants. I share this perspective, as a prairie biologist and land manager of several decades. Remnants include the “stuff ” of prairies and savannas and many species, conditions, and functions that we have not thought about or discovered. We cannot truly fathom the complexity or function of remnants fully, particularly because they exist without the context of the original, expansive native landscape. These remnants are rare, so it is urgent to nurture them. But their rarity and relatively small size also make it crucial to observe and study them so they can be used as models for critically needed planted examples of prairie.

Photo courtesy of Icecube Press

The authors embrace these concepts, but miss one important detail: sometimes remnants and plantings co-exist. Though the authors clearly have a deep connection to Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge, Dean mistakenly describes this site solely as a reconstructed prairie when, in fact, it includes 800 acres of remnant prairie and savanna. When remnants co-exist with plantings, or are embedded within a larger planted landscape, the relationship can be mutually beneficial. Planted prairie can protect remnant edges or increase the overall prairie size, potentially making remnants viable long-term, compared to tiny, isolated parcels existing in a hostile landscape. On the other hand, mycorrhizal fungi, or native plants or animals, especially invertebrates harbored in remnant refugia, could begin to populate adjacent plantings making them more remnant like. In 2019, a rusty-patched bumble bee, a native species federally listed as endangered, was photographed by a sharp-eyed volunteer on planted prairie at Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge. Perhaps this bee or its ancestors originated from one of those embedded remnants!

Amid the many wonderful inclusions in this book were some puzzling ones, like the photo of the non-native Chinese mantis in the conversation about home. The conversation exuberantly and delightfully describes many native species emerging in spring, and this image of an exotic species seems discordant with the ideas the essay portrays. Though I understand the loss of native ash trees to invasive emerald ash borers can have great impact on the ecosystem, I found it awkward and peculiar that Crosby chose to make this story the centerpiece of her side of the conversation on diversity. Though ash trees are native, they are not prairie or savanna species and are typically cut and removed when found in native grasslands. Why not draw from the endless possibilities of stories about diversity inherent in tallgrass?

Finally, though the authors frequently returned to the theme of tallgrass representing home, some essays seemed to imply that humans were not part of “nature,” at least not as it involved prairie or savanna. This is a misconception I strive to dispel, even though our species has wrought such devastating destruction on the natural landscape. People have a place in our native grasslands and have for thousands of years. Native people influenced the character and composition of grasslands in the way they lived and certainly by their frequent use of fire on the vast, flammable prairies. We need to retool the way people now think about the world by elevating the value of native ecosystems, both remnant and planted versions. I would argue that Crosby’s and Dean’s Tallgrass Conversations is an excellent vehicle to contribute to that transformation. By stewarding, nurturing, celebrating, healing, and yes, being healed by tallgrass, we become part of the prairie just as certainly as when we repeat the ancient tradition of setting life-giving fires to them.

Photo by Justin Hayworth

One of the conversations involved the word “surprise,” but my greatest surprise was the overwhelming gut reaction I had to Crosby’s essay on persistence. Here she weaves a story of an autumn-prairie-colored quilt made by a friend, which she puts on her bed in the fall. This quilt leads her to ponder the countless efforts of people to stitch the pieces of our damaged prairies back together. It is a healing essay. It is about stewards, conservationists, newcomers to prairie, activists, artists, gardeners, and yes, quilters, all of whose work helps in healing prairie. For each effort named, there is the italicized word, stitch, that echoes like a drumbeat throughout the essay. I felt each staccato stitch in my gut as an affirmation. Tears unexpectedly rolled down my cheek. It is because of the loss, the hope against hope, and my soul’s prayer for healing, even knowing prairie is essentially gone. I probably felt this conversation so acutely because I have tried so hard in so many ways to heal prairie, and myself in the process. To me, this is a pivotal essay in the book.

To readers I would say, read this book! Savor it. Devour it. Read carefully and study the photographs. Make notes if you will, or look up new words. And when you are done, do as the authors advise and share this book. Make your own conversations with tallgrass and with the people of prairie and savanna.