The idea of writing about backyard prairie restoration started in Kansas.

In late August, I was researching prairie-based stories in Kansas when I came across a short audio piece, only a few minutes long, about a small-scale prairie restoration in Edgerton, KS. Residents of that city had voted to install a prairie plot in a local park to teach children about the prairie and entice them into exploring the larger patches of prairie beyond the playground. It’s a long-term project, since the prairie will take a couple years to get established. City officials hope that children who grow up with the prairie will have an interest in restoring even more of it when they reach adulthood.

Kansas, the third biggest producer of sunflowers in the U.S., is known as the Sunflower State. Among many other wonderful attributes (including road-trip attractions like the world’s biggest ball of twine,) it is home to the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, the only national preserve dedicated to the preservation of America’s tallgrass prairie. Today only four percent of the tallgrass prairie remains, with the largest areas being the Flint Hills of Kansas and the Osage Hills of Oklahoma. The Edgerton plot is one example of how the state is starting to recover their original landscape.

Though this story started in Kansas, my research did not remain there for long. Within days of discovering the Edgerton restoration, I learned of a community in Minnesota which was creating prairie restorations in its residents’ own yards. As a person who lives in an area of Colorado that is more desert than prairie, this was new to me; when I started this research, I’d had no idea that prairie restoration was a concept, much less something people could do in their own backyards. I began to look more deeply into the phenomenon of the backyard prairie, and fell down the rabbit hole of prairie restoration, both big and small-scale.

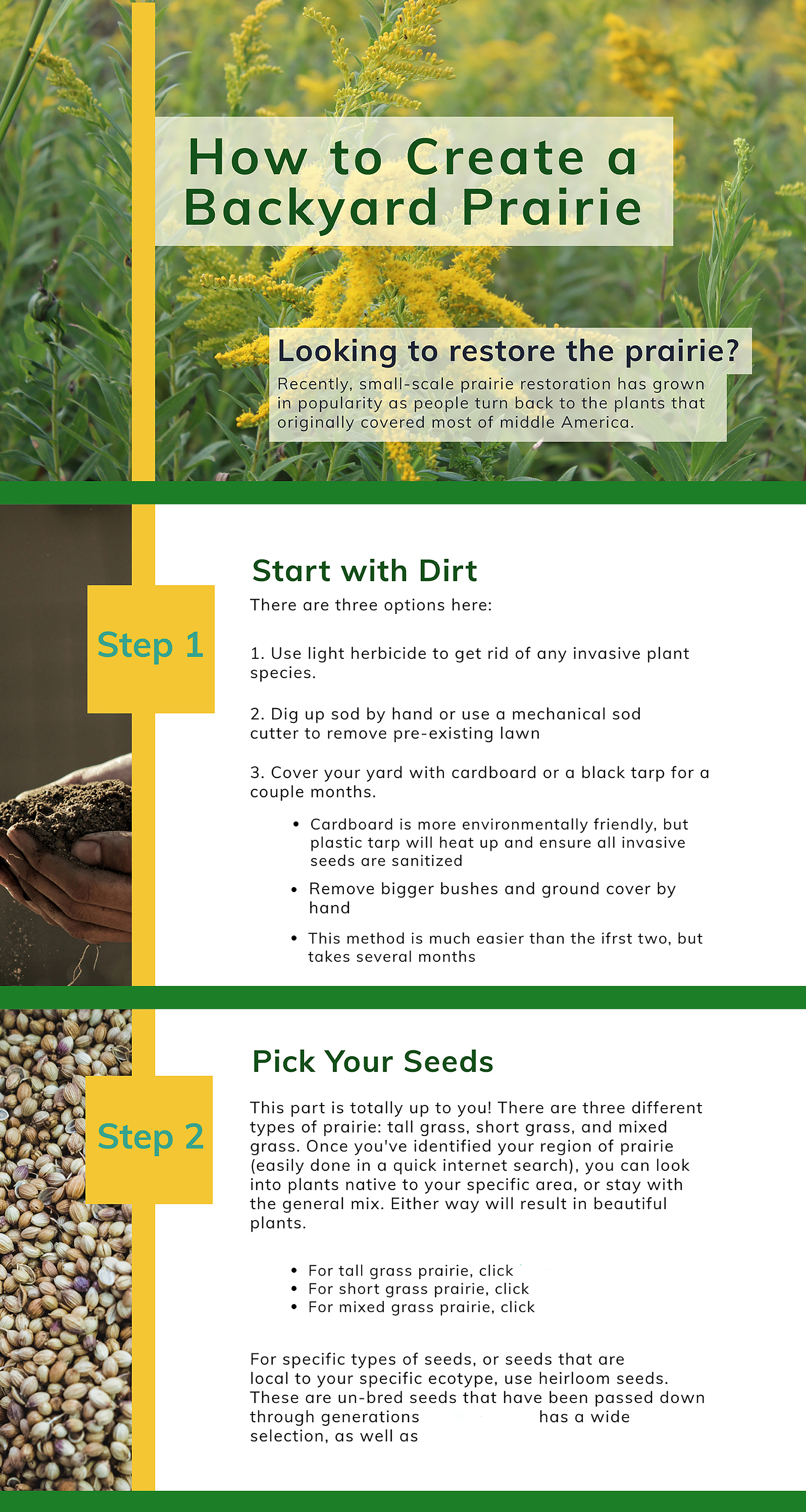

As it turns out, seeds, dirt, and a little hard work are all anyone needs to start their own prairie. There are countless articles and resources online about people who have gone through the process themselves, and how they’ve reaped the benefits of these efforts years later. When planted in the right environment, prairie eventually becomes mostly self-sufficient and requires less upkeep than a traditional grass lawn. It will attract native insects and animals, increasing biodiversity and animal-watching prospects, and resulting in a healthier ecosystem wherever it grows. If you’re inspired to grow your own prairie, the infographic which follows is a step-by-step starting point for any beginner. Growing your own prairie will take patience and time, but remember—this is a project bigger than just you, and you are joined by other people all over the prairie. Good luck!

A prairie garden has replaced the lawn outside Grinnell College’s Macy House. Photo by Jon Andelson

For sources and further reading, visit:

Iowa National Heritage Foundation

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Five Steps to a successful Prairie Meadow Establishment