In March 2019, devastating floods hit the Missouri River floodplain and lasted for almost an entire year. Corey McIntosh and his wife, Tina Popson, who farm along the Missouri in western Iowa, were displaced by the flooding and had to leave their family farm to seek shelter. Mr. McIntosh’s great-grandparents purchased that land in the early 1940s, and the family has been farming it ever since. Since long before the ‘40s, flooding has been a part of the history of the Missouri, but in recent years flooding has become more frequent and stronger. With climate change and all of the alterations made to the river, recent flooding is some of the worst in history, and this is likely to continue to cause ruinous losses for operations like Mr. McIntosh’s.

Across the country, there is a need to control water supplies because there are consequences to both shortages and excesses of water. As the longest river in the United States, the Missouri River experiences the challenges of both. Many other places in the United States do, too; the problems could arise anywhere. Often, humans then attempt to control any aspects that they can to make water systems and management more consistent.

Human intervention on the Missouri River began in the early 1930s. At the turn of the decade, during the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, many farmers in the Missouri River basin lost their crops from alternating catastrophic floods and drought. The net result was that many were forced to abandon their farms. When flooding continued to tear through the Missouri Basin, in 1943, Congress tasked the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) with creating a flood control plan for the Missouri River and Basin to help bring farmers back to the region. 1

The USACE is a branch of the United States Army that consists of three divisions: an engineer division, a military construction division, and a division that handles civil works. The civil works sector of the USACE focuses on creating and maintaining infrastructure in the United States and overseas. The Corps also provides military facilities for combat zones, as well as conducting research and development of a variety of technologies. 2 On the Missouri River, the USACE is responsible for maintaining the river’s waterways, dams, and reservoirs. There are eight main areas that the USACE prioritizes when it comes to these efforts, including flood control, water supply, water quality, irrigation, hydropower, fish & wildlife, recreation, and navigation. The USACE manages these responsibilities through the Water Control Manual for the Missouri River Basin, which is also known as the Master Manual.

In recent years, flooding along the Missouri River has been all too common. Corey McIntosh described his experience in an essay he wrote about the flooding in March 2019. 3 According to Mr. McIntosh, “counting the 2019 flood, five of the top ten highest crests of the Missouri River in recorded history have occurred since 2010,” and the past 15 years of farming were considerably more difficult than they ever were before. Mr. McIntosh claims that this is because of the 2004 revision of the Master Manual, which deprioritized flood control, making it coequal in importance with the seven other areas that the USACE manages.

“The USACE is tasked with trying to balance eight authorized purposes without any of them holding a clear priority,” Mr. McIntosh said in his piece. “Unfortunately, the needs of these eight purposes are almost always in a state of constant tension with each other, with one seldom requiring the same river management practices as another. A compromise approach seeking balance among them rarely truly benefits any of them. The USACE is trying to serve eight different masters while managing to please none of them.”

Under USACE’s management, Mr. McIntosh said, flooding has become more frequent and intense.

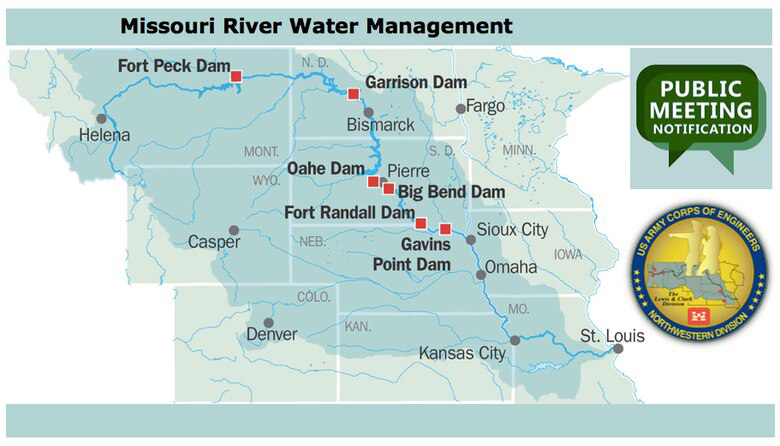

Map of the Missouri River region courtesy of the United States Army Corps of Engineers

“In many ways, the 2019 flood [was] more unpredictable and more devastating than the unprecedented flooding that occurred in 2011,” he said. “Most of the rain and snowmelt runoff in March 2019 entered the Missouri River via tributaries below the reservoirs of the USACE dam system. However, more proactive steps by the USACE might have mitigated the extent of the damage.” Mr. McIntosh goes on to say that while the flood waters that the USACE released from a nearby dam did not directly cause the 2019 flood, the Corps’ policies made the impacts of flooding significantly worse. Mr. McIntosh relates how much worse the flooding was in 2019 than in 2011:

“Compared to 2011, we had very little time to prepare for this year’s events. This year, we had to try to accomplish in about three days the same amount of preparations that took us over three weeks in 2011. Also, weather conditions this year, during the little time that we did have to prepare, made it exceedingly difficult to do what needed to be done. Rain and soft roads made it difficult to evacuate grain in a timely fashion. We were fortunate that we had only a limited quantity of grain remaining in storage, and we were able to evacuate it just prior to the arrival of the floodwaters. Many others, especially to our south, were not so lucky.”

Corey McIntosh stands at the edge of Missouri River floodwaters near his home in July 2019. Photo courtesy of Corey McIntosh

In addition to the loss of crops to flooding, Mr. McIntosh also faced financial impacts and destruction to his other property. He says that this stems from a combination of politics and the weather in 2018-2019:

“Severely depressed crop market prices, due to the US government’s ongoing trade war with China, compelled many farmers to keep grain in their storage bins throughout the winter, hoping for higher prices in the spring and summer, banking on a resolution to the trade war in the coming months. Consequently, a greater percentage than normal of grain bins were still full when the unexpected floodwaters came in mid-March. The subsequent rupturing of those bins and the spoiling of the enclosed grain is a devastating loss, which is likely uninsured.

“Crop insurance coverage terminates once the crop has been harvested from a field, and typical farm/ranch property and casualty insurance policies exclude flooding as a covered peril.

“Without a way to salvage or market those spoiled bushels, many affected farmers are facing a catastrophic financial blow, during a time when farm incomes have already greatly eroded during the past few years. Many farm operations were already facing potential net operating losses in 2019, even before this devastation. Some severely impacted farmers are now facing a loss of income for two years-worth of crops: the damaged grain that was stored from the 2018 harvest and a potential inability to plant a crop in 2019 on land that is still inundated by floodwaters at a date when our normal planting window is fast approaching.

“We sustained some damage to buildings and equipment that we were not able to evacuate. We have likely lost most of the fertilizer that we applied to the fields in the Fall of 2018 for the 2019 corn crop. This is an uninsurable loss of over $100 per acre. Organic debris (stalks, stubble, logs, etc.) has accumulated up to a couple feet thick in certain fields and drainage systems, with no good method for clearing or disposing of it.”

Floodwaters cover the McIntosh-Popson farmstead March 2019. Photo courtesy of Corey McIntosh

McIntosh grain storage bins flooded in March 2019. Photo courtesy of Corey McIntosh

While the United State Department of Agriculture later did partially compensate farmers for the lost bushels, Mr. McIntosh is not the only one who is critical of the USACE’s original decisions. In a Des Moines Register article, “Iowa Farmers Say Army Corps Puts Endangered Species Above People,” published in March of 2019, a farmer who sits on the Missouri River Recovery Implementation Committee, Leo Ettleman, says that “the Corps failed to provide [him] with important information about flooding levels as waters rose this month, leaving it to local levee managers and emergency officials to assess the danger.” 4 “The Corps left us to die,” he said. Since then, Ettleman and other farmers have turned to Congress to change the priorities of the Missouri River’s management to focus on flood control. Mr. McIntosh sums up the situation simply: “The current system isn’t working for anyone.”

Dr. Chris Jones, a research engineer at the Iowa Institute of Hydraulic Research/Hydro Science and Engineering at the University of Iowa, manages a network of university-monitored water quality sensors across the state of Iowa. He also holds that the USACE is having difficulty trying to balance its priorities. He says that many of the problems connected to the floods have arisen because “the Missouri River is a highly modified system.” As he explains:

“We’ve dammed the [Missouri’s] upper reaches upstream of Sioux City [Iowa]. There’s a series of large reservoirs on the Missouri itself, and then there’s many other impounded streams that are tributaries to the Missouri. These impoundments, or dams [see map above], are in the Dakotas, Nebraska, and Montana. We’ve channelized the lower portion downstream from Sioux City down to St. Louis to try to make the Missouri navigable for shipping. We did these things a long time ago, beginning in the 1930s. And when we did these things, we divorced the river from its floodplain. So now, when there is a flood, it tends to be a catastrophic event. And we’ve tried to farm in the Missouri River floodplain in Iowa and other states, and it’s really difficult to manage these high flow events based on the system that we have, to try to optimize flood protection both for the farmers and for the cities that are along the Missouri.”

Dr. Jones’s explanation accounts for why the effects of the floods are so devastating when they happen, and he also says that while he does not agree with everything that the USACE has done, he claims it has been unfairly criticized and is having difficulty balancing all its priorities due to the number of unnatural changes made to the river back in the 1940s that made it more difficult to contain excess flooding.

A third perspective is offered by John Remus, Chief of the USACE’s Missouri River Basin Water Management Division, Northwestern Division. In an interview, he explained that balance is not an accurate way of describing how the USACE functions, and emphasized that, while there are eight authorized purposes, in reality there is only a single priority: the USACE wants to avoid any loss of life due to action by the organization. He said that management can also shift depending on what the hydrological condition of that specific time are.

For example, 2018 and 2019 were large runoff years, and therefore lots of water was coming in and the USACE’s focus was on flood control. Whenever the water level in the river gets lower, raising the specter of a drought, the focus shifts to providing water for navigation and downstream water supplies. As Mr. Remus explains, the USACE is “not prioritizing one [priority] in particular; the priorities haven’t shifted over the last decade or so. The hydrologic cycle has made it appear that there’s been a shift, but there really hasn’t. [The USACE’s] political operations have not changed since 1960. In [the USACE’s] Master Manual, some of our water supply and navigation have changed but certainly not the flood control operations.”

Land reclamation equipment stuck in flood-deposited sand, December 2019. Photo courtesy of Corey McIntosh

One relatively new major problem—climate change—has forced an alteration in USACE priorities. Dr. Jones explains: “There was the whole bomb Cyclone event, and then a lot of snowpack in the mountains in the headwaters of the Missouri, an overall increase in precipitation, especially in the Dakotas over the last 30 or 40 years. That’s what’s changed. And the system wasn’t designed for these climatic events that we’ve had here since 2011, which was first of the big recent floods.”

Mr. Remus at the USACE concurs that climate change is taking place and that it is not a debatable topic. However, he also suggests that when it comes to making decisions for the future, there is still a lot that’s unknown. “Whether we’ve reached a new normal, or we’re on our way to a new normal, that we don’t know, or at least not definitively enough to make decisions with water control management, where we’re learning more every day.” As the system design stands, Mr. Remus said, it “has a certain channel capacity to it that was designed for a certain set of hydrologic conditions that existed back in the 1930s, 40s, 50s, and 60s.”

Additionally, environmentalists argue that not enough is being done for endangered species that live along the river, while some say that navigation has too much priority. There are many species such as the endangered pallid sturgeon and shorebirds that are affected by the changes in the Missouri River. Mr. Remus says that “the mainstem reservoir system and the bank stabilization and navigation project are working as they were intended to work.”

There are many opinions about what should be done to move forward, but no plan suggests an easy solution. Corey McIntosh says that ultimately “Congressional action will be necessary to ensure that floodcontrol regains top priority among the currently eight priorities for the Missouri River system.” To encourage this action, he suggests that everyone “write and call their elected state and federal officials to express their concerns about the repeated flooding in this part of the world.”

Mr. Remus agrees that Congressional action will be necessary, but cautions that no large policy change will fix the flooding problem. He says USACE already has flood control as a core mission, with policies already in place to mitigate flood damage. The perpetual problem in all this, he says, is funding: “Everything takes money, Congress has to approve it, and when these projects were built back in the 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s, the Corps came in and built the projects… we didn’t have a lot of input from the locals. [W]e’re required to do that now, and that’s a good thing… That all takes time. That takes a lot of leadership on every level to make things happen, particularly when you’re talking about something as large as the Missouri River Basin. It’s just going to take some time, some patience, and people with the patience to see it through.”

Dr. Jones says the Missouri should be allowed to reclaim its floodplain—an option which he admits would not be ideal for farmers, “but if you want to reduce the severity of these floods, you’re going to have to do something [about them], or [else] live with them. You can build the levees higher and higher and higher, and who knows how high they have to be anymore when we have these unprecedented climatic events.”

This being said, Corey McIntosh says that all eight of the authorized purposes for the Missouri River are undoubtedly noble pursuits. However, the recent changes to the operation of the river have departed from the well-established historical precedent in place for many decades when the government actively encouraged and incentivized the residential, agricultural and economic development of the river basin.

“It’s as if a local government encouraged homeowners and businesses to build in and move to a new housing development, but then a few decades later decided that the best use of that land would now instead be to construct a new interstate highway through it,” he says. “I certainly think that the home and business owners would expect to be made whole for the loss of their homes and livelihoods in the name of a redefined public interest. If creation of habitat and preservation of species is deemed to be a worthy public interest, then the cost of that pursuit should be shared by the public and should not be expected to come primarily at the expense of a select group of private citizens who have only done what the government historically asked them to do.”

There is a long, difficult journey ahead to find the best way to manage the Missouri River. As Dr. Jones says, the USACE has “something over there that’s really difficult to manage, and there’s a lot going on.”

Editor’s Note—As we were going to press, Mr. McIntosh informed us about additional legal proceedings that are currently happening:

In ongoing litigation, a judge in the [United States] Federal Court of Claims has already issued a trial opinion that addresses the detrimental impacts on flood control that have resulted from the revisions the USACE made to its Master Manual in 2004. 5 Judge [Nancy] Firestone states that “in the 1979 Master Manual, the Corps expressly provided that flood control was its first priority, and that fish and wildlife were the last priority.” However, with the 2004 revision of the Master Manual, Judge Firestone found that the Corps must now “always consider the impact of other … authorized purposes on fish and wildlife because the Endangered Species Act has a higher precedence than [the] other authorized [Missouri River System] purposes,” which represents a dramatic departure from historical priorities. Following the issuance of the 2004 Master Manual, the USACE undertook a program that included modifying and degrading Missouri River flood control structures, such as wing dikes and protective bank revetments, with the purpose of destabilizing the Missouri River banks for habitat purposes.

While it may be debatable exactly how much such river management practices increased the severity of the catastrophic flooding that occurred in 2011 and 2019, Judge Firestone found in her court opinion that practices implemented in the 2004 Master Manual have certainly led to increased flooding in many years since, including 2007, 2008, 2010, 2013 and 2014 (flooding in years after 2014 were outside the scope of the litigation). Judge Firestone said: “By its actions, the Corps has caused foreseeable water surface level increases and thus more flooding than would have occurred without the Corps’ System and River Changes."

Corey McIntosh surveys stunted corn crop and barren flooded land, July 2019. Photo courtesy of Corey McIntosh

1 Reclamation. ‘The Inception of the Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin Program.’ Bureau of Reclamation, www.usbr.gov/gp/multimedia/archive/glimpse/picksloan.html

2 ‘About Us.’ Headquarters U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, www.usace.army.mil/About

3 Corey McIntosh, ‘Yet Another Devastating Flood.’ Crescent Connection, March 2019

4 Donnelle Eller, ‘Iowa Farmers Say Army Corps Puts Endangered Species above People.’ The Des Moines Register, March 28, 2019, www.desmoinesregister.com/story/money/agricul-ture/2019/03/27/iowa-flooding-army-corps-puts-endangered-species-above-people-law-suit-claims/3232773002

5 United States Court of Federal Claims. Ideker Farms, Inc., Et Al. v. United States of America. March 13, 2018. https://ecf.cofc.uscourts.gov/cgi-bin/show_public_doc?2014cv0183-426-0