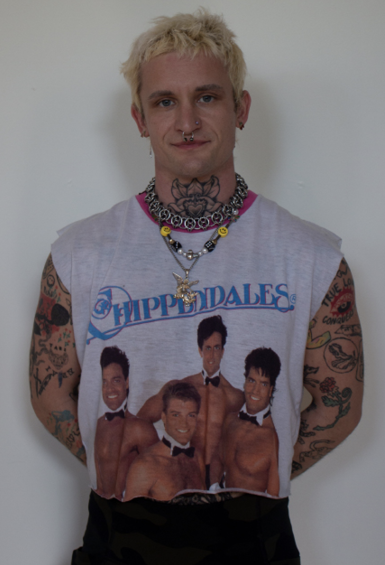

As I walk into Arrowhead Tattoo studio in Faifield, Iowa, I’m immediately struck by Dom Rabalais’ bold personal style. The 32-year-old multimedia artist, tattooer, and Fairfield native is sporting tight leopard print leggings, a cropped Chippendales t-shirt and a platinum bleached hairdo. His style matches his bright and extroverted demeanor as he greets me and introduces me to the studio. He hands me a thick binder bursting with sketches of tattoos, and although the purpose of my visit to the studio is simply to talk to him, I find myself curiously flipping through his sketch-book. Rabalais’ tattoo work is vibrant and playful, with a childlike sense of wonder and mischief that emanates from each design. After surveying his sketches of flower chains, small scarab beetles, and wolves, I remember one of his designs that I had liked that I saw online: a small jester. I mention this to him and before I know it, he’s furiously scribbling at his desk, rendering the vintage Halloween-inspired design, ready to tranfer it from the page to my skin. Next thing I know, I’m sprawled out on a table in the studio getting prepped for a spontaneous tattoo as we discuss his work.

Rabalais’ tattoo work and paintings have gained significant traction online lately, largely through platforms such as Instagram, where he posts his work for thousands of followers that include other notable and emerging artists. His colorful, cartoony work feels fresh and of-the-moment, and it’s clearly resonating with people in the Fairfield area, as he has been booked and busy since his return to Fairfield in 2020. Despite his growing following, however, Rabalais didn’t set out specifically to become a “tattoo artist.”

Dom Rabalais poses wth two of his canvses and, of course, the canvas he has made of his body

“I never thought ‘and someday I’ll be a tattooer being interviewed about tattooing’ or something like that. I was kind of like, ‘Well, my friends want tattoos and I shall give them some.’”

Rabalais’ tattoo journey began when he was a teenager in the 2000s, when he discovered stick and poke tattooing through a feature titled “The DIY Guide to Everything” in the punk ‘zine Razor Cake. A “stick-and-poke” is a type of tattoo that’s created by spreading ink on the skin and then using needle-sticks to introduce the ink beneath the surface of the skin. Because the equipment is relatively inexpensive and the technique requires less precision, it’s often seen as the go-to tattooing method for beginners. From there, Rabalais began tattooing in what he calls an “evil manner,” using safety pins to scrawl designs on himself. “Occasionally, my friends would want something abhorrent tattooed on them, and I could do it in a very rudimentary way.”

Later in his 20s, Rabalais developed his tattoo skills further while living as a touring musician. He recounts the story of his former bandmate and late friend who bought him his first tattoo gun. Stick-and-poke tattoos can be time consuming, and since he wanted lots of tattoos done quickly, he ordered Rabalais what he referred to as a beginner’s “Baby’s First Tattoo Gun.” Rabalais would then use this gun to tattoo his friends, bandmates, and the owners of whatever house they were crashing at that night during their tour. “As a result, I gave a lot of tattoos that were not the world’s best , but were very much the kind of tattoos that one gives and receives in a punk house.” In those days, punk houses were spaces where members of a given punk scene lived, performed to packed local audiences, and partied. It was through the trial and error process of rendering these punk house tattoos that Rabalais refined his craft, learning things about the process that he could only learn b giving a lot of tattoos.

“There’s a bond between the tattoo-er and the machine, the wielder of the tool and the tool itself, that can only be built through experience,” he says.

One can see the youthful, rebellious energy of DIY music channeled into Rabalais’ designs like his series of warped cherubs or his offbeat sketches of the Tasmanian Devil from Looney Tunes. Later, he explains that music was and in many ways still is his primary artistic outlet. “My main thing is playing music and going on tour all the time.” He explained that before the pandemic, his plan was to be on tour indefinitely, and it wasn’t until recently that he was able to dive deeper into tattooing and painting as other outlets for artistic expression. He explains that music, art, and tattooing are often tied together through the imagery they feature. He describes the “dialectical back and forth” between his paintings and tattoos, with each borrowing designs from the other. When I ask Rabalais how his focus shifted largely to tattooing, he jokingly admits that it’s all about attention.

“OK, I’m not trying to be like, ‘Oh, no one likes the music,’ but as far as things that I have been successful at doing, I feel just in general, people seem to respond really well to the paintings and tattoos, which is great because I mean, in the end, all I want is validation and attention.”

He says this last part with a smirk and a chuckle, but the attention he has received for his visual art and tattooing is no joke. From residencies and shows in galleries in Ohio and Washington to becoming a regular tattoo artist at Arrowhead Studios in Fairfield, Rabalais has managed to build a successful career out of his visuartwork, allowinl g him to quit his indexing job and pursue his art full time. Rabalais’ major shift in focus toward tattoo art came after returning home to Fairfield after living in New York City for several years.

He was born and raised in Fairfield, a small college town located in southeast Iowa. At first glance, the town might appear to be like many other small towns in Iowa: sleepy, unassuming, conservative. However, Fairfield boasts a unique history as the home of the Maharishi International University, a private college centered around the practice of transcendental meditation where Rabalais’ mother worked during his upbringing. The college, founded in 1973 by Indian yoga guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, has gained a sort of cult following known locally as “the Movement,” and has created the small Iowa town’s singularly offbeat culture. This unique, non-conformist culture has influenced him in many ways.

When I ask him if growing up in Fairfield has affected his art or style, Rabalais replies with “Well, definitely in the way that my mom was very supportive.” “I acknowledge and am aware that growing up in Fairfield was unconventional. It was also the kind of thing where ‘I don’t really know what I don’t know.’ I have no baseline to compare it to. My perspective on it has changed a lot over the years.” Growing up, he attended what he describes as the Maharishi equivalent of Catholic school run by the Movement. After graduation, he later attended the university’s art school where he began to develop his artistic chops. It was during his time in school that Rabalais began to pick up on “the secret history of America.”

“Just to go full tinfoil hat here, there are things about the Movement that I find to be kind of buck wild. I wouldn’t even say these are conspiracy theories. It’s history. It’s fact that people don’t generally talk about.”

From here, the two of us both go “full tinfoil hat” as we dive into a long and winding conversation surrounding the Movement’s connections to geopolitics and culture, its alleged ties to COINTELPRO, an FBI backed program run from the ‘50s-70s, designed to surveil, infiltrate, and disrupt leftist political organizing in the US, and its relationship to ‘60s counterculture and LSD. The conversation was fascinating—albeit, a little off topic—but more than anything it lent context to Dom Rabalais as a man and artist. While his upbringing in Fairfield might not play an explicit role in his art, I could see how these components of his past—the Maharishi schooling, the punk house life, the constant touring—all come together to influence Rabalais’ wonderfully zany and unconventional signature style.

The Evolution of an Artwork: After consulting with his client on the design, Dom Rabalais bdgins by outlining the figure

A tatoo design sometimes requires several visits before a it is fully developed, particularly if—as here—Rabalais is working on several tatoos at once. During later sessions, the artist will add detail and color

While returning home after living in New York City has brought Rabalais lots of new opportunities, his move back wasn’t under the best of circumstances. It was the passing away of his father during the pandemic that prompted him to return to Fairfield where he could take care of his mother. “It was hard to be like, ‘Ok, Mom, just deal with that.’” Rabalais tells me about how he moved himself and his partner out of New York and across the country, back to Fairfield, with his partner eventually relocating to Minneapolis. While his plan isn’t to live in Fairfield for the long term (he already splits his time relatively evenly between Minneapolis and Iowa), he has found comfort and solace in returning to the prairie.

Rabalais seated at a workstation dedicated to another of his passions: music

“I can come back and spend time with my mom and help to fix things around the house. I mean, in a more existential/emotional way, I need to figure out being alone and experiencing solitude without having a mental breakdown at the same time. I feel like now I have to confront that part of myself that is so afraid of solitude. And yeah, small-town Iowa is a great place to [do that].”

In between bouts of Iowa solitude, you can catch him traveling all over the country working on projects from an arts festival in northwest Arkansas to doing tattoo residencies in Portland to painting fences in Nashville and putting on his own visual art shows in Ohio.

Rabalais finishes the final touches on my tattoo and snaps a few pictures to post on his Instagram account. I admire the new piece of art on my leg: a playful ode to my birthday being on April Fools’ Day. As we exchange goodbyes, I find myself already craving another tattoo and make a mental plan to return one day for another new piece.