In our current energy culture, we feel entitled to unlimited and wasteful energy use, whenever and wherever we want it, and that it ought to be cheap too. A fantasy of limitlessness. We assume that we can have a 100 percent “clean” energy economy without making any changes in the way we live, do business, or conduct our daily lives.

A few years ago, when attending a conference on clean energy for climate stability, I heard presentations on plans for 100 percent renewable energy for each state, mostly through wind and solar electricity. Clearly, we do need to rapidly discontinue the use of oil, coal, and natural gas, and invest in renewable energy. The question, “What about the need for significant energy conservation?” yielded the response from the prominent engineer who was presenting: “With 100 percent of our energy needs met with wind and solar, there is no need to conserve energy!”

Discussions of the future of energy are often framed in terms of supply; what energy sources will we use to keep our economy going? The fossil fuel industry has an on-going and vigorous smoke-and-mirrors show offering numerous false energy solutions—algae, ethanol, carbon capture, nuclear, clean coal, clean gas—all of which involve more fossil energy, more toxic materials generated, and land degradation. The narrative of the environmental movement is that solar and wind energy will meet our unlimited energy demand without any fundamental changes in the way we live or use energy and materials.

As a nation, and as local communities, we need to frame our discussion of the future of energy (and climate) in terms of habits, community processes, and policies that lead to significant reduction in energy demand and material use for a livable future. It is not enough to “decarbonize,” but also necessary to detoxify (i.e., alternatives to daily materials in our lives that are derivates of fossil fuels) and use less material. How do we build a social movement that offers practical alternatives to a culture of extreme consumption?

In Our Land, Ourselves, a book by the Trust for Public Land 1, the authors ask a provocative question: “The conservation movement succeeds brilliantly in saving hundreds of thousands of acres of land each year, but somehow provides no broadly recognizable cultural counterpoint to America’s otherwise materialistic society. The conservation movement is largely silent on choices Americans make about how one should live. Is there no dissonance in saying that a movement is devoted to saving land but not devoted to fighting the consumption that destroys the land?” I keep thinking about this foundational question and what “a recognizable cultural counterpoint” might look like in practice. What are the key elements of such a culture, and what are some of its recognizable features?

In Our Only World, 2 Wendell Berry offers insights related to these questions: “The long-term or permanent damage inflicted upon all life, by the extraction, transportation, and use of fossil fuels is certainly one of the most urgent public issues of our time, and of course it must be addressed politically. But responsibility for the better economy, better life, belongs to us individually and in our communities.” Berry suggests that we not only need renewable energy, but also less energy and material when he writes, “The unlimited use of any energy would be as destructive as unlimited economic growth, or any unlimited force. If we had a limitless supply of free, nonpolluting energy, we would use the world up even faster than we are using it up now.”

Sky in Cedar Falls, Iowa. January 23, 2023

We need guidance! If you have a ton of credit card debt and need help addressing the situation, you go to a consumer credit counselor. Their advice: cut up your credit cards and develop a strict plan to get you back on track towards living within your means. Similarly, our continued and ruinous dependence on fossil energy and extreme material consumption are proving to be like the credit cards that we need to put aside.

The consensus is that human activities are at the root of the climate crisis, and yet there is so little said about what exact human activities we are going to change in our households, communities, and regions! We need to urgently develop a robust plan to use less, to live within our means, in this case, within the energy and material limits of our region and the planet. What might such plans look like? Well worth a community conversation.

Where might we draw inspiration that we are capable of impactful collective action to address a crisis? Naomi Klein discusses this in This Changes Everything when she writes, “…we humans have shown ourselves willing to collectively sacrifice in the face of threats many times, most famously in the embrace of rationing, victory gardens, and victory bonds during WWI and WWII. Indeed, to support fuel conservation between 1938 and 1944, the use of public transit went up by 87 percent in the U.S. and 95 percent in Canada. Twenty million U.S. households-representing three fifth of the population-were growing victory gardens in 1943, and their yields accounted for 43 percent of the fresh vegetables consumed that year.”

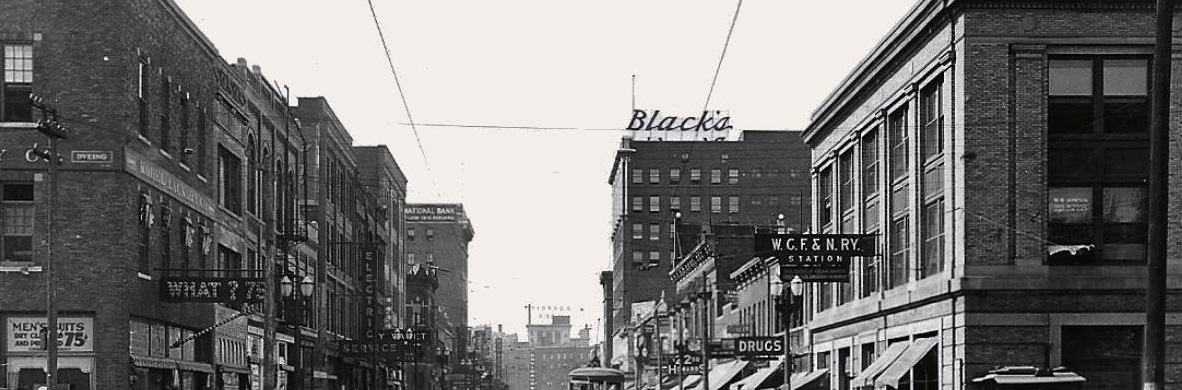

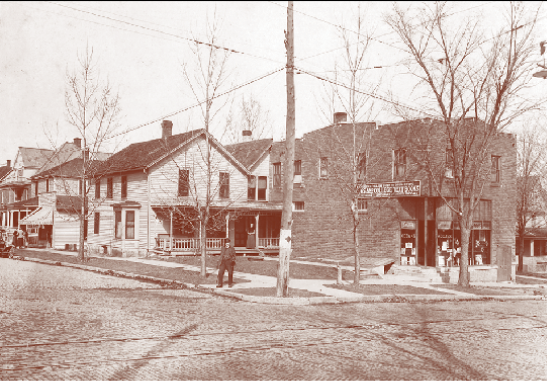

And of course, back then, there was robust public transportation in place to depend on. I often share with my students an image of an electric trolley in operation in my neighborhood in Cedar Falls in 1890. Clearly, we have regressed in public transportation! As late as 1959, there were daily passenger trains all over Iowa in addition to electric trolleys in so many Iowa communities, taking away the need for car ownership, which is very costly and requires a vast quantity of materials.

Trolley tracks on the street with overhead electical lines at College Hill in Cedar Falls, Iowa.

Same with clotheslines! It is not that hard to estimate the length of a train carrying coal needed to dry clothes in a community if every household used a clothes dryer, and pretty much everyone does in the U.S. (For Cedar Falls, Iowa, the coal train would be roughly a mile long). Are we not even willing to start using less energy by doing the simplest of all carbon emission reduction, by simply hanging our clothes on clothes racks or clotheslines? We can do similar estimates of when the lights are left on unnecessarily, when spaces are air-conditioned unnecessarily, and the list of system-wide wasteful energy practices go on and on. It is much cheaper to cut energy waste than put up solar panels (which require energy and material to manufacture) to keep on wasting energy!

Trolley system on East 4th St. Waterloo, Iowa, 1957

Public transportation, a local and regional food system, fresh-air clothes drying, and gardening are all very achievable; a lot less traveling is doable and not catastrophic like destructive storms, floods, or droughts. The sooner we adopt these personally and communally, the more options we will have as we make more significant progress towards less energy and more community.

Renewable energy, while necessary, is not enough, and is not the whole story. Community scale innovations and cultural approaches that result in energy and material down-sizing are going to be key to a livable future. Institutions of higher learning can be a force in clarifying the confusing false energy solutions, technological fundamentalism, and injustices of an extractive economy. They can also help greatly by demonstrating the multitude of ways people of a region can develop their cultural capacity to live within the limits of their region without inflicting damage to other regions. Furthermore, they can create opportunities for their students to be involved in turning what we already know into action at the community scale in their region.

Sources:

1 Our Land, Ourselves: Readings on People and Place. 1999. Edited by Peter Forbes, Ann Armbrecht, and Helen Whybrow. Page 184. The Trust for Public Land.

2 Berry, Wendell. 2015. Our Only World. Chapter 5, Less Energy, More Life. Counterpoint Press.

3 Klein, Naomi. 2014. This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate. Page 16. Simon & Schuster.