The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) and Superior National Forest are traditionally known as Anishinaabe land. The story of the Anishinaabe peoples—also known as Ojibwe or Chippewa—is one of resilience, persistence, and hope. The interconnected waterways winding across the Superior National Forest have been critical travel routes for the Anishinaabe for thousands of years, since long before fur traders from Europe began displacing Indigenous tribes. The fight to protect these lands has endured for centuries, and it continues in full force today in response to proposed sulfide-ore copper mining in the headwaters of the Wilderness. The preservation of this land is not only a matter of environmental preservation but also a matter of upholding Ojibwe treaty rights. The recent success of the Boundary Waters protection movement in mitigating mining threats is due in part to legal action and advocacy by the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe (MCT), and if permanent protection is achievable it will likely require continued Indigenous initiative. In order to fully appreciate the modern efforts of the MCT to protect the BWCAW, we must first consider the history of land treaties between the federal government and these tribes in some detail.

Indigenous History in Northeastern Minnesota

The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness is a vast expanse of interconnected lakes, streams, and forests that spans 1.1 million acres of unspoiled natural landscape in northeastern Minnesota. It is the most-visited Wilderness in the country and holds 1,100 lakes within its boundary. Here, the air is crisp and the water is clear, reflecting the majestic sunrise each daybreak. Loon calls echo across the lakes, cutting through the meditative sound of waves lapping against the rocky shoreline. The dense forests of spruce and pine trees seem infinite, sheltering the swaths of wild blueberry patches and the wildlife that devour their fruit. At dusk, bald eagles are replaced in the sky by countless stars that shimmer off the glassy water. When Mother Nature is feeling generous, the northern lights illuminate the darkness with a flickering green light that dances behind the tree line.

Sunset over Ojibwe Lake, which rests on the edge of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW). All photos courtesy of Zach Spindler-Krage unless otherwise noted.

This region, with its inexpressible beauty and abundant natural resources, has been home to Indigenous peoples for roughly 10,000 years. When Paleo-Indians first entered North America during the late glacial episodes of the Late Pleistocene period, Minnesota was still covered by glacial ice and large melt-water lakes. Areas of northern Minnesota did not become ice-free until 11,500 B.C.E, with lake formation beginning between10,000 and 9,500 B.C.E. By 9,200 B.C.E, archeologists estimate that northeastern Minnesota was likely habitable; the newly uncovered land was rapidly revegetated with spruce forest and tundra grassland, providing food for woodland animals like mastodon and grassland species like mammoth and caribou. However, the rugged terrain and thick vegetation make archeological surveying difficult, and archaeological evidence for Early Paleo-Indian occupation in this area is sparse. Most available evidence places the first significant growth in Indigenous inhabitants of the area in the Late Paleo-Indian period (8500 - 7900 B.C.E). 1

In roughly 1000 C.E., ancestors of the Anishinaabe people began to move into northeastern Minnesota from the northeast coast of North America. The migration was likely driven by the region’s abundance of natural resources. The Anishinaabe are skilled hunters, fishers, and gatherers, and the Boundary Waters area provided a wealth of fish, game, wild rice, and medicinal plants.

Yet, the Boundary Waters are not just a source of physical sustenance for the Anishinaabe, but also of spiritual nourishment. The area is filled with sacred sites, including ancestral burial sites, rock formations, and islands believed to be inhabited by spirits. 2 Furthermore, the lakes, rivers, and forests of the region are seen as living entities, imbued with their own spirits and personalities. Anishinaabe stories charge members of the tribe with protecting the natural world and honoring the spirits of the land and waterways.

In the mid-17th century, French traders made first contact with Ojibwe tribes, a subgroup of Anishinaabe, along the west shore of Lake Superior. Between 1680 and 1761, French traders and Ojibwe engaged in a period of intricate fur trade. The Ojibwe provided animal pelts, winter food supplies, canoes, and snowshoes, while the French provided guns, cloth, clothing, copper kettles, and tobacco. Following the defeat of France in the Seven Years’ War, ending with the Treaty of Paris in 1763, British companies began their own fur trade with the Ojibwe. Three prominent fur trade companies — the North West Company, the XY Company, and the Hudson’s Bay Company — established their own presence in northern Minnesota and continued to trade manufactured items for animal pelts. The Ojibwe played a crucial intermediary role in connecting the British to other Indigenous tribes and transporting furs and other goods between European traders and those tribes. After the War of 1812, both American and British trading posts were present in the Border Lake region, which offers a canoe route from the Boundary Waters to Lake Superior along the Canadian border. 3

The Ojibwe Treaties of 1837 and 1854

By the 1830s, in the midst of westward expansion, the United States government began forcibly removing Indigenous tribes from their lands in the upper Midwest. In 1837, with little choice but to move, Ojibwe and Dakota leaders ceded a massive swath of what is now east-central Minnesota and western Wisconsin to the U.S. government. The land ceded by the Ojibwe included Mille Lacs Lake, one of Minnesota’s most famous fisheries; however, at this time, the government was primarily interested in logging the white pine forests east of the Mississippi River. In exchange for the millions of acres of land, the government promised payments to the Ojibwe of $35,000 each year for twenty years. The payments were completed in the form of cash, goods, and services that included food, blacksmith shops, and a yearly ration of $500 worth of tobacco. 4 The tribes were also granted the right to hunt, fish and gather on the ceded land, which became a pivotal provision of the treaty agreement in the following decades.

Map of the territory ceded by Ojibwe Tribes in 1837 and 1854. Graphic courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission.

In 1848, surveyors discovered copper along the north shore of Lake Superior. Immediately, mining companies in Michigan began pressuring the federal government to open the area for mining, which required another land cession from the Ojibwe. 5 The 1854 Treaty of LaPointe, signed by eighty-five Ojibwe leaders, ceded 5.5 million acres of the Arrowhead Region of Minnesota, including what would become the entire BWCAW. In exchange, the tribes received annual payments of less than $20,000, split among cash, goods, agricultural supplies, and school funds. The Lake Superior Bands received an extra $90,000 to help pay their debts to traders. 6 As with the 1837 treaty, the Ojibwe agreed to sell their land only if they retained the right to hunt and fish on ceded territory. Despite the discovery of several extensive copper deposits, the expected rush of miners never developed at this time.

Tribal officials signing the treaty of LaPointe in 1854. The treaty ceded all of the Lake Superior Ojibwe lands to the United States in the Arrowhead Region of Northeastern Minnesota, in exchange for reservations for the Lake Superior Ojibwe in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota.

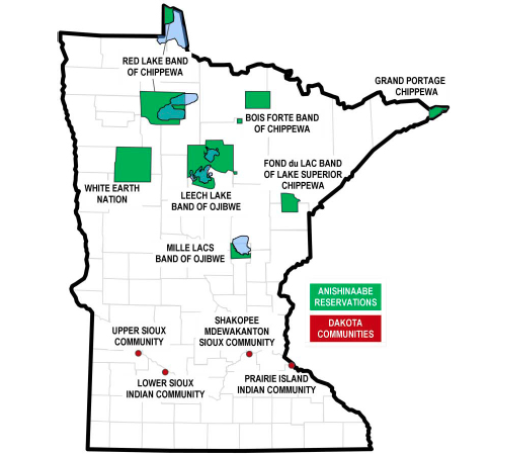

As a part of the 1854 treaty, the Ojibwe also received several one-time payments to help them resettle on reservation land. These reservations are still heavily populated. The Grand Portage Indian Reservation, east of the Boundary Waters, is home to the Grand Portage Band of Chippewa; the Bois Forte Reservation, to the west, belongs to the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa; to the southeast is the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. These three groups join the Leech Lake, Mille Lacs, and White Earth reservations as part of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, which has roughly 41,000 members. 7

The eleven federally recognized Tribal governments in Minnesota, including the six members of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. Graphic courtesy of Minnesota Department of Transportation

Based on the legal interpretation of the prominent treaties of 1837 and 1854, the signatory Ojibwe Bands retain usufruct rights: the right to live off the land and make a modest living from hunting, fishing, and gathering from the ceded territory’s resources. This interpretation results from the Reserved Rights Doctrine, which establishes that “any rights that are not specifically addressed in a treaty are reserved to the tribe.” In other words, treaties outline the specific rights that the tribes ceded, not the rights that they retained. 8 Despite this legally-mandated interpretation of the rights granted to the Ojibwe Bands, the State of Minnesota applied its hunting and fishing laws in the ceded territory to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike for over a century, violating the treaties.

The Battle Over Treaty Rights

View overlooking Lake Superior and the Superior National Forest

In 1985, in an effort to reclaim long-denied treaty rights, the Grand Portage sued the State of Minnesota in federal court. The Fond du Lac and Bois Forte Bands subsequently joined the lawsuit to negotiate a satisfactory settlement. 9 The state and three bands came to an agreement in 1988 whereby the state makes an annual payment to the bands — $1.6 million to the Grant Portage and Bois Forte and $1.85 million to the Fond du Lac — and the bands establish their own regulations on Tribal members. Under the agreement, the Bands’ regulations restrict commercial harvest, big game seasons, spearing, netting, and other activities that are “of concern to the state” for tribal members. 10 The Grand Portage and Bois Forte Bands remain in the agreement, which continues successfully to date.

While this agreement was a positive step for the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, it did not commit to a legal conclusion regarding the validity of the treaty rights. In fact, despite entering the agreement, the state argued in separate cases in 1988 and 1999 that the tribes’ use rights had been dissolved, citing an 1850 Executive Order. 11 The order, signed by President Zachary Taylor on February 6, 1850, states that the “hunting, fishing, and gathering of wild rice upon the lands, the rivers, and lakes included in the territory ceded to the United States…are hereby revoked; and all of the said Indians remaining on the lands ceded as aforesaid, are required to remove to their unceded lands.” 12 Additionally, the state argued that the entrance of Minnesota into the union in 1858 terminated the use rights.

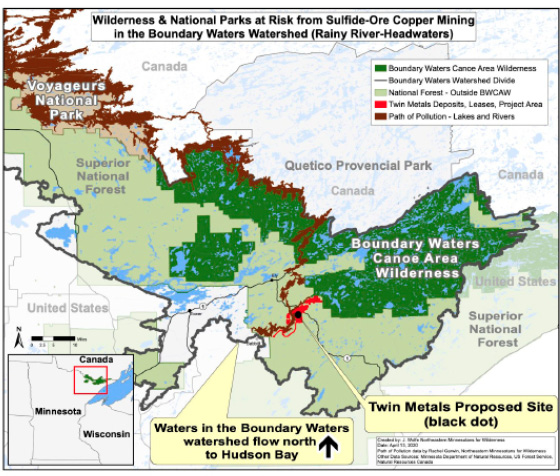

Map of the proposed sulfide-ore copper mine and the likely path of pollution. Graphic courtesy of Save the Boundary Waters Campaign

However, in Grand Portage Band of Chippewa of Lake Superior v. Minnesota (1988), the U.S. District Court in Minnesota affirmed the Ojibwe Bands’ authority to regulate the exercise of their enrolled members’ hunting, fishing, and gathering rights in the ceded territory. Since 1989, the U.S. Department of Interior has encouraged the participating Bands to exercise these rights sustainably by granting funds to maintain natural resource programs. 13 Yet, the state continued to complicate — and in some cases prevent—the ability of the bands to exercise their treaty rights.

Consequently, in 1990, the Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa filed suit seeking a confirmation of their use rights and an injunction against the State of Minnesota to prevent it from interfering with those rights. In 1999, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the Ojibwe’s rights to the ceded land, stating that the 1850 Executive Order had no source of authority because it did not “stem either from an act of Congress or from the Constitution itself.” 14 The Court’s affirmation of the treaty rights was not only important for the Ojibwe but for all tribes with treaty use rights; ultimately, the decision ensures that treaty rights are retained unless a treaty, statute, or executive order clearly expresses a future intention to abrogate those rights. In the case of the 1837 and 1854 treaties, no such stipulation or intention was included, which allows the bands to continue their hunting, fishing, and gathering with explicit legal protection. 15

In 2017, the state and Fond du Lac Band agreed to a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) that formalized collaborative efforts regarding the collection and sharing of data that informs annual hunting, fishing, and gathering regulations. The MOU solidifies acceptable harvesting methods, establishes wildlife surplus levels and moose population protections, and creates committees consisting of Tribal and state representatives where resource management issues and disputes can be discussed. The MOU includes a stipulation, signed by both parties, ensuring that the 1837 and 1854 treaty rights are interpreted consistently. At the signing of the agreement, former Fond du Lac Band Chairman Kevin Dupuis highlighted the gravity of this event: “The exercise of our hunting, fishing, and gathering rights under our 1854 treaty is central to the lives, culture, and traditions of the Fond du Lac people. Because of the critical importance of these rights, the Band has worked extensively to ensure proper management of the natural resources on which those rights depend.” 16

Growing Threat of Mining Near the Boundary Waters

Cherokee Lake in the BWCAW

A significant portion of the 1854 treaty land is within the Superior National Forest, which comprises nearly 4 million acres in northeastern Minnesota. The BWCAW lies within the Superior National Forest, and much of the best hunting, fishing, and wild rice harvesting occurs in the area’s watershed. This is critical because of a new threat: mining.

Historically, the Boundary Waters have been strictly protected. The one million acres that now make up the Wilderness were formally designated in 1964 by the Wilderness Act. However, the Wilderness Act allowed for unsustainable practices to continue within the area, including the use of motorboats, mining, and some logging. The 1978 Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act restricted these activities, making the area one of the most heavily protected regions in the U.S. 17 Yet, while the Wilderness Area and federal buffer area are protected from mining, the surrounding area, including the headwaters, is not. The Boundary Waters — with its 165,000 annual visitors and $540 million ecotourism economy — is threatened by proposals for toxic sulfide-ore copper mines in its headwaters and watershed. This type of mining, never done before in Minnesota, has proven to be extremely damaging; a peer-reviewed report by Earthworks, an anti-mining advocacy group, studied fourteen sulfide-ore copper mines in the U.S. and found that thirteen had had significant impacts on water quality in their catchment areas. 18 The mining process is risky. First, rock is blasted from pit walls and sorted into metal-bearing ore and waste rock. Since less than one percent of the rock contains copper or nickel, ninety-nine percent of the rock has little economic value and will sit indefinitely in the waste storage facility or rock piles. No metal recovery method is fully effective, so metals, sulfides, and residue from explosives are commonly left behind in the waste. Acidic mine drainage develops when these sulfide minerals are exposed to air or water. Chemical reactions can turn these otherwise benign minerals toxic. 19

As soon as pollutants enter the interconnected waters, they are likely to spread throughout the entire ecosystem. Depending on whether the pollution occurs north or south of the Laurentian Divide, the toxic waste will either flow south into Lake Superior or north through Voyageurs National Park, emptying finally into Hudson Bay.

The mining proposal by Twin Metals Minnesota, a subsidiary of Chilean mining firm Antofagasta, would operate next to the headwaters of the Boundary Waters near Ely, Minnesota, for twenty years. The lease has been passed between mining companies since 1966, but the severity and imminence of the threat have grown rapidly in recent years. President Obama first proposed withdrawing the area from mining in 2016, but President Trump approved the leases for the project in 2019. When President Biden took office, he initiated a U.S. Forest Service environmental assessment of the potential damage of the mine, and a judge ordered a pause on any action until the legality of the Trump administration’s decision to renew the leases was evaluated. Ultimately, the Biden administration canceled two leases required to build and operate the mine. 20

On January 26, 2023, in the most significant action to date, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, signed Public Land Order 7917, effectively banning sulfide-ore copper mining on 225,504 acres in the watershed of the BWCAW. In short, this federal step ensures the protection of the established acreage for the next twenty years. 21 It is the longest moratorium that the Department of Interior can issue; permanent protection would require Congressional action. This is a major step in the environmental protection movement, and the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe (MCT) has played an integral role in the ruling.

Advocacy for the Protection of Tribal Livelihood

In one example of the ruling’s far-reaching effects, in January 2020, the MCT sent a letter to Congress announcing its support for the Boundary Waters Wilderness Protection and Pollution Prevention Act. The bill, authored by Minnesota Fourth District Congresswoman Betty McCollum, would expand the existing mining buffer zone around the Boundary Waters by an additional 234,000 acres.

In the letter, MCT president Cathy Chavers references the 1854 treaty that granted hunting, fishing, and gathering rights to the Fond du Lac, Grand Portage, and Bois Forte Bands. Because of these rights, Chavers explains that the Bands have a “legal interest in protecting natural resources, and all federal agencies share in the federal government’s trust responsibility to the Bands to maintain those treaty resources.” 22

Ojibwe harvesting wild rice in 1939. Photo courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society

Chavers also emphasizes the historical significance of the region to the MCT and the likely effect of mining pollution on the surrounding reservations: “The fish in adjacent waters are subject to consumption advisories designated by the Minnesota Department of Health because of mercury in their flesh,” Chavers says. “Sulfide-ore copper mining will increase the amount of mercury in fish, a toxin of great concern to our members who depend on wild caught fish for their sustenance. Wild rice and terrestrial species will also be at risk, as pollution and habitat destruction will have wide reaching impacts.” 23

Much of the water in the BWCA is currently clean enough to drink without filtration

The letter concludes by expressing appreciation for the healthy environment and economy that offer sustenance to the MCT and warns that it is all at risk if any mining proposal moves forward. “It is unacceptable to trade this precious landscape and our way of life to enrich foreign mining companies that will leave a legacy of degradation that will last forever,” says Chavers. “We need this protection before it is too late, and the future of this area is now in your hands.” 24

The MCT was also cited extensively in findings and recommendations from the U.S. Forest Service. In October 2021, the Forest Service submitted a withdrawal application to the Interior Department’s Bureau of Land Management, which manages the subsurface mineral estate under the national forest. While collecting extensive public input regarding the withdrawal, the Forest Service conducted a science-based environmental assessment to evaluate the potential impacts of prohibiting new mineral and geothermal exploration and development within the Rainy River watershed for the next twenty years. 25 The analysis and decision were informed by 225,000 comments, three public meetings, and, notably, two Tribal consultations.

One of the predominant findings from the Tribal consultations was the potential impact on wild rice harvesting. To the Ojibwe, wild rice “was endowed with spiritual attributes, and its discovery was recounted in legends. It was used ceremonially as well as for food, and its harvest promoted social interaction in the late summer each year.” This significance remains. Since wild rice is sensitive to fluctuations in water level and changes to alkalinity and water chemistry, mining would likely decrease yield, which has already been reduced by industrial development in the area. 26 According to the 1854 Tribal Authority, an Inter-Tribal resource management agency that is cited heavily in the assessment, there are 521 waters that support wild rice growth within the 1854 Ceded Territory. In the consultation, the Tribes also reference the subsistence value of uncontaminated fish and the cultural value of moose, sugar maple, white cedar, paper birch, and berries. 27

The locations most used by Band members are within the “area of highest potential for mine infrastructure,” so degradation would be likely to occur on these lands. Overall, the amount of federal land within the 1854 Ceded Territory has already been reduced by nearly fifty percent since the treaty was signed, so the protection of the remaining land is of utmost importance for the Tribes. The assessment states that “wildlife habitat, plants, wetlands, and associated cultural resources of value to the tribes…may be permanently lost.” 28

Ultimately, the Forest Service concluded that mining activity in this area would disproportionately affect the Bands, breaking the federal government’s legally mandated trust responsibility with tribes. Based on the strong evidence for the adverse effects of mining presented by the Bois Forte, Grand Portage, Fond du Lac, and White Earth Bands, the Forest Service recommended a mineral ban on 225,504 acres in the Wilderness watershed. 29 The Department of Interior implemented this recommendation in January 2023, protecting the Boundary Waters for the next twenty years.

The Ultimate Goal: Permanent Conservation

Despite the success, there is still potential for the government to reverse course when the administration or Congress changes hands. However, the Ojibwe Bands are actively fighting to proactively protect their land from economic extortion and environmental degradation. On July 14, 2022, the Fond du Lac and Grand Portage Bands filed a landmark Clean Water Act lawsuit against the Environmental Protection Agency Region in federal court. This is the first lawsuit any tribe in the U.S. has filed against the EPA over changes to water quality standards. The lawsuit aims to challenge the EPA’s decision to approve the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency’s overhaul of “Industrial Use” and “Agricultural Use” water quality measures. The Bands argue that the elimination of numeric standards is likely to exacerbate pollution in waters that flow through the Ojibwe reservations. 30

In addition, on May 9, 2023, the Bois Forte, Fond du Lac, and Grant Portage Bands of Lake Superior Chippewa entered into an agreement with the U.S. Forest Service to work collaboratively to manage the Superior National Forest. The Memorandum of Understanding states that the Forest Service “recognizes the Bands as original stewards of lands now encompassing the Superior National Forest and outlines procedures to ensure that Tribal input is meaningfully incorporated into Forest Service decision-making.” The MOU recognizes that tribes have already been playing a major role in studying wildlife, contributing traditional ecological knowledge, and advocating against development in the region, but they will now have a greater say in the protection of culturally-sensitive areas, coordination of forest management goals, and the selection of conservation projects. Cathy Chavers, MCT president, articulated the weight of this agreement: “We, as Tribal Leaders, are charged with caring for our natural resources. This includes our elders and youth. We also must think of the next seven generations by building partnerships and strengthening relationships to work together to achieve that common goal.” 31

The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and Superior National Forest are Anishinaabe lands. When the Anishinaabe were forced to cede their land in 1837 and 1854, their use rights to the land remained. Yet, the realization of these rights has taken decades of legal challenges, advocacy, and persistence. Ultimately, the Chippewa Bands were successful in achieving legal protection of their treaty rights. But they are not inclined to stop here. As a primary current threat to their livelihood comes in the form of sulfide-ore copper mining proposals, the Bands will continue to fight for permanent federal protection of this land. They intend to fight until politicians recognize the value of a pristine, spiritually-rich Wilderness and choose to protect it from exploitation.

1 Susan C. Mulholland, Stephen L. Mulholland, Gordon R. Peters, James K. Huber, & Howard D. Mooers, “Paleo-Indian Occupations in Northeastern Minnesota: How Early?” North American Archaeologist 18, no. 4 (1998): 371-76.

2 Susan C. Mulholland et al., “Paleo-Indian Occupations,” 381-86.

3 United States Forest Service, “Historical Contact,” United States Department of Agriculture, accessed on March 28, 2023. https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/superior/learning/historyculture/?cid=fsm91_049856#:~:text=French%20Fur%20Trade%20

4 John Enger, “Explaining Minnesota’s 1837, 1854, and 1855 Ojibwe Treaties,” MPR News, February 1, 2016. https://www.mprnews.org/story/2016/02/01/explaining-minnesota-ojibwe-treaties

5 Minnesota Legislative Reference Library, “Copper-Nickel Studies and Non-Ferrous Mining,” Minnesota Legislature, January 2023. https://www.lrl.mn.gov/guides/guides?issue=coppernickel#:~:text=Copper%2Dnickel%20deposits%20have%20been,metals%20developed%20in%20the%20region.

6 Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, “1854 Treaty,” DNR, accessed on March 15, 2023. https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/aboutdnr/laws_treaties/1854/index.html

7 Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, “Who We Are,” MCT, accessed on March 5, 2023. https://www.mnchippewatribe.org/

8 Douglas P. Thompson, “Understanding Chippewa Treaty Rights in Minnesota’s 1854 Ceded Territory,” 1854 Treaty Authority, 2020. https://www.1854treatyauthority.org/images/ToHuntandFish.updated2020.pdf

9 MDNR, “1854 Treaty.”

10 United States District Court Fourth Division, “Grand Portage Band of Chippewa of Lake Superior v. State of Minnesota,” 1985. https://data.glifwc.org/ceded/legal.references/Grand.Portage.v.Minnesota.No.%204-85-1090.pdf

11 Karii Krogseng, “Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians,” Ecology Law Quarterly 27, no. 3 (2000): 773-78.

12 Legal Information Institute, “Supreme Court of the United States 119 S.Ct. 1187 143 L.Ed.2d 270,” Cornell Law School, accessed on April 3, 2023. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/526/172

13 MDNR, “1854 Treaty.”

14 United States Department of Justice, “Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band,” January 4, 2022. https://www.justice.gov/enrd/minnesota-v-mille-lacs-band

15 “Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians,” Oyez, accessed on April 24, 2023. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1998/97-1337

16 Office of Mark Dayton, “State of Minnesota and Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Reach Agreement Resolving Outstanding Fish and Wildlife Issues Related to 1854 Treaty,” State of Minnesota, December 8, 2017. https://www.leg.mn.gov/docs/2018/other/181224/governor/newsroom/indexee39.htm

17 “History of the Boundary Waters and its Protections,” Save the Boundary Waters Campaign, April 7, 2021.

18 “What is the Threat?” Save the Boundary Waters Campaign, accessed on May 1, 2023.

19 “Sulfide Mining Fact Sheet,” Minnesota Environmental Partnership, 2017. https://www.mepartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/MEP-Sulfide-Mining-Fact-Sheet-2018.pdf

20 United States Forest Service, “BWCAW Overview and History,” United States Department of Agriculture, accessed on March 7, 2023. https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/superior/specialplaces/?cid=stelprdb5203434

21 United States Department of Interior, “Biden-Harris Administration Protects Boundary Waters Area Watershed,” January 26, 2023. https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/biden-harris-administration-protects-boundary-waters-area-watershed

22 Catherine Chavers, “Minnesota Chippewa Tribe Letter of Support for Copper Mining Ban Near Boundary Waters,” Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, January 31, 2020, 1. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6792326- Chippewa-Tribe-Letter-of-Support

23 Catherine Chavers, “MCT Letter,” 2.

24 Ibid.

25 Lee R. Johnson & Juan Martinez, “Rainy River Withdrawal: Tribal Traditional Needs and Values Report,” United States Forest Service. June 2022, 1-8. https://eplanning.blm.gov/public_projects

26 Ibid, 3.

27 Ibid, 5.

28 Ibid, 6.

29 United States Forest Service, “Rainy River Withdrawal: Environmental Assessment,” June 2022.

30 “Fond du Lac and Grand Portage Bands File Suit Against EPA to Reverse Approval of Minnesota’s Damaging New Class 3 & 4 Water Quality Standards,” Indian Country Today, July 15, 2022. https://ictnews.org/the-press-pool/fond-du-lac-and-grand-portage-bands-file-suit-against-epa-to-reverse-approval-of-minnesotas-damaging-new-class-3-4-water-quality-standards

31 Greg Seitz, “Tribes and Forest Service Announce Co-Stewardship of Superior National Forest,” Quetico Superior Wilderness News, May 9, 2023.https://queticosuperior.org/tribes-and-forest-service-announce-co-stewardship-of-superior-national-forest